A Summer of Performance

The summer in Italy and elsewhere is festivals’ season. Right before going on holiday then, we take you with us to theatre and performative arts festivals throughout the country, some we already went to, some we recommend you to end up your summer with, and others to plan in for next year. As superorganisms these festivals made us think about liveness, collectivity, performativity, (post)disciplinarity and why not also about subversion and revolution.

At a flash dancing rhythm, with Affecting the Norm Jennifer Beals gives us an insider view of the festival’s visions, networks and machines. Then she takes us with her to the festivals she has been to: Castiglioncello, Santarcangelo, Drodesera, and (suggests us to go to) Short Theatre. Marta Federici and Giulia Crispiani went together to Centrale Fies to see the Live Works, and they used that as a hint to talk about other stuff. In Undisciplined Praxis, Federici unfolds the pedagogical potential of a “post-disciplinarity.” In Learing by Doing, Giulia Crispiani dives into the essence and history of Centrale Fies.

Affecting the Norm

Summer festivals in Italy are a central appointment for people working or interested in the field of performing arts, and over the years they grew of importance due to their peculiar programs and explored topics, difficult to find elsewhere. So, what is a festival? What have festivals become for spectators and professionals?

First of all it’s important to mention that performative arts—and contemporary art tout court—festivals are not only scheduled during the summer season; for instance, important appointments are Live Arts Week, curated by Xing in Bologna or FOG organized by the Triennale, and Danae Festival dedicated to dance, both in Milan.

A festival is a complex organism that lives in a suspended time and gives space to experimentation and research, both on an artistic level and within the community, in the encounter and clash with the public space. Clearly, there are multiple ways to be a spectator in a Festival, and we have a privileged point of view as insiders, who live the festival machine from within and see the other festivals as an opportunity to see things almost impossible to intercept elsewhere in Italy.

It is no coincidence that in 2016—last year of Silvia Bottiroli’s artistic direction—Santarcangelo Festival presented a collection of books titled How to build a Manifesto for the Future of a Festival, each one dedicated to a specific topic. A way for the Festival to reflect on itself and to disclose matters, rather than drawing conclusions. The first volume Build the time reflects on the making of a festival. In the conversation Festival as thinking entities Daniel Blanga Gubbay (currently co-director at Kunstenfestival des Arts) highlights the risk of thinking of a festival as a state of exception, for it could reaffirm the norm, and asks “how could a festival be something in itself and not a counter-norm, because,” continues Gubbay, “the risk of every heterotopic place is to be neutralized by naming it as something else.”

This is a thing to keep in mind when looking at the whole landscape of Italian festivals, as the ones we chose to cross are still somehow “states of exception” that attempt to activate various strategies so not to be neutralized. We have to think for instance about the time of the festival beyond the festival, what is there yet it’s hard to be seen, or better to say, what’s visible only in part, such as residency programs, productions and the continuative support to some artists; last but not least the network among festivals. In these past few years, we have seen strong collaborations, in particular between Santarcangelo Festival, Short Theatre and, the unfortunately now suppressed Terni Festival, protagonist of one of the sad pages of Italy’s contemporary cultural history.

“To be open to the unexpected, to allow something to slip, and not to predict everything” said Francesca Corona, Short Theatre’s co-director and freshly appointed consultant for Teatro India in Roma, speaking about a festival that leaves its doors open, as an organization and a curation that let things happen to see what could take place… indeed operating in the meantime—to get back to the text above mentioned.

Mk, Bermuda. Photo Andrea Macchia. Courtesy Santarcangelo Festival

In a conference about the future of the festival in 2016, Wiener Festwochen’s director Christophe Slagmuyder affirms, referring to Santarcangelo: “it is not just about producing or presenting works but primarily creating the conditions to gather and exchange. Here, one perceives the opportunity to break through things you see rather than just watching and consuming them.” Is it actually possible to create alternative ways of consumption within the festival? Can festivals be the places to rethink fruition, in order to counter the typical capitalistic mechanism? Maybe yes, and in this sense there are several virtuous attempts.

Festival are becoming places for knowledge production, where communities meet each other to create a collective and temporary one that follows the flow of the festival, and produces valuable exchanges even at the party. Festivals function as workshops with an eye to the future that question the relation with the institutions, challenging them on a practical level with the introduction of different pedagogical models, such as the School of Exception and Autoscuola della Notte in Santarcangelo, or the huge and important project Piattaforma della Danza Balinese in Santarcangelo; but also in the attempt to imagine new ways to dialogue with the present, for example by sharing spaces and ideas between the Master di Studi e Politiche di genere dell’Università Roma Tre (Rome’s MA in gender studies) and Short Theatre or the rethinking of the concept of award in Centrale Fies’ Live Works Performance Act Award.

These complex organisms have turned the exception into norm, by deconstructing their apparent opposition and affirming their own identity beyond this dichotomy. A specific yet fluid identity of a transitory, immersive, evanescent and imperfect nature. If the Italian theatre seasons and programs are structured to make immediately clear what is dance, what is theatre and what is music, and to clearly define their objects and their spectators—as the dance audience, the theatre audience and so on—the festivals stand today as hybrid places, where disciplines can tangibly encounter and mingle.

Non-standard formats, performance, installations, their intersections and declinations can exit mostly in a space and time established first of all by the community of the spectators. This community is united first by affection, curiosity, inclination, participation and only after by expectations. The contract between spectator and festival is definitely a different kind of agreement compared to the one between spectator and theatre. It deals with the set up of an environmental aspect, through sharing the attempt more than the outcome’s evaluation, as it relies on a mutual trust—constantly (re)shaped and negotiated—more than on the recognition of an authority, as well as on the “festive” matrix intrinsic to the festival.

Although genres and categories are still named, and each work “belongs to” a specific one both for the public institution that distribute funds and for the disoriented audience, multidisciplinarity is the core ministerial mantra, the reference point of the very experience of the festival; magmatic universes are forming and boiling inside the defined categories, where things already exist otherwise and beyond.

This condensed and exceptional temporality—that festivals inhabit as they come into being—is what ignites the status of the happening, where experiencing is more relevant than knowing, and praxis takes over planning, tactics over strategy. When part taking to a festival, one find herself immersed in simultaneity (while watching a show in a venue something else is starting elsewhere; meanwhile the staff is welcoming artist performing the day after and the audience of the following concert is arriving). Things simply happen organically, overlapping, unfolding as something more contagious than mere causality. The impression is to find ourselves in a self regulated organism. The dialectic between prevision and act creates spontaneous forms of collective intelligence, where every single thing happens within a chain of acts, subjective states and conditions, in spontaneity and reciprocity.

Only the intensity of the gaze upstream—meaning not only attention to details but also the capacity to mirror and question your own practice—can create an openness downstream. An openness that deals with fear and loss of control, allows to face the unexpected and a way that it becomes significant. In this continuous back and forth between control and abandonment, underlying the life of a festival, there lies its own revolting potential: festivals are still places to experiment what seemed impossible elsewhere.

Short Theatre, 2018.

The depth of the gaze is also a matter of obstinacy: to stop existing as a desiring machine and become desire yourself, practicing it and putting it to work. In the fragility and flexibility that define them as direct expression of a rampant capitalism that dissolves and produces precarity, festival are workshops of possibilities that have taken their exceptionality very seriously, and try to chip the edge of it in every edition. These borders are eroded by both internal and external dynamics. By nature, festivals have privileged relationship with the territory, as their sudden and extended appearance creates a special and complex, sometimes problematic, relationship with the area that hosts them. Festivals are tentacled organisms that, unlike theaters and galleries, insinuate themselves between the folds of the place’s everyday life and demand a continuous and close exchange. A non-standard format par excellence, the site specific project can exist mostly inside the festival, as the relationship with the community and the territory is so direct and intense that does activate a dialogue between apparently incompatible worlds.

It is important to stress again on the networking between festivals. This can be either informal or structured through projects—around artists, staff, information, materials—as as the quantity and direction of this exchange and the concurrence of some of them, creates a temporal and spatial extension that gives substance to the very idea of alliance. The contagion born within the folds of all those exceptions to the norm, instilled inside the essence of the festival, effectively produces a surplus, able not only to establish itself but also to wander and affect other times and places. As if to say: we are not the exception that proves the rule, but the exception that undermines it.

Jennifer Beals goes to festivals

Along with Santarcangelo, Armunia/Festival Inequilibrio Castiglioncello represents a piece of history in the jagged magmatic path of contemporary theatre and performative arts in Italy. The Festival takes places at the end of June, the beginning of the festivals’ season and since 22 editions it takes places in different locations around the classical town where Italian middle class usually spend their summer holidays. Castiglioncello is also famous in cinema history (as the place where Gassman and Trintignan were leading to in their spider in Il Sorpasso), and an hamlet of Rosignano Solvay municipality—a city born in the early ‘900 around Solvay’s chemical plant, who determines its morphology an resemblances. From the exotic and alien “white beaches” whitened by the soda, to the skyline dominated by industrial chimneys or the typical brick houses for the workers. In Rosignano everything is called Solvay, even the theatre, made also of bricks, one of the main venues of Inequilibrio together with the evocative Pasquini Castle, submerged in a pine forest along the cliffs. The Castle is the office of the Association who organizes the Festival and hosts companies in residency during the year.

Castiglioncello is one of the main places caring for and curating Italian artistic’s projects—both emerging and established—hosting them in the phase of investigation, development and rehearsal. Over the years Armunia has been able to build a network of interconnected artistic and cultural activities, open to contemporaneity. Since the 80s Castiglioncello has been the stage for a lot of Italian and foreigner dance, theatre, music productions (among others Massimo Castri and the Micha van Hoecke’s Ensemble), becoming one of artists’ most beloved places. The last edition hosted some of the most interesting figures of the national and international scene, young generations and companies who have made the history of the contemporary Italian theatre and dance (MK/Michele Di Stefano, Marco D’Agostin, Davide Valrosso, Abbondanza/Bertoni, Fortebraccio Teatro, Enzo Cosimi, Raffaella Giordano and VicoQuartoMazzini), making a leap forward in terms of imagination hosting some site-specific and non-standard formats (for example Attika by Industria Indipendente and Annamaria Ajmone, Archeologia del coraggio by Elena Guerrini and Il Padre Nostro by Babilonia Teatri).

Attika, Annamaria Ajmone e Industria Indipendente. Photo Antonio Ficai. Courtesy Armunia

This year closes the three-years period of Eva Neklayeva and Lisa Gilardino’s artistic direction. In this third year the atmosphere of Santarcangelo Festival has been characterized by a “Slow and Gentle” mood, as declared by the subtitle of this edition. Much space dedicated to the Italian scene with a gaze particularly focused on dance with artists like Cristina Rizzo, Mk, Marco D’Agostin and Alessandro Sciarroni, among others; project realized with locals, like Francesca Grilli’s Sparks which involved local children that opened a dialogue with adults, overturning power structures; space also for international projects such as Public Movement or Studio Dries Verhoeven. A three-year period marked by themes related to the body, its issues and political status, that opened collaborations with collectives like Macao, in an attempt to explore new formats of visions and relations between scene and audience.

Santarcangelo festival has an ancient history, it has arrived at its 49 edition, it is about to celebrate an important birthday with Motus’ artistic direction next year. During the days of the Festival—knowingly Santarcangelo has no proper theatre space—this town in Rimini province transforms itself in an open-air theatre welcoming the community. Nonetheless, the atmosphere of the festival can be perceived also during the year. Beside the residency program bringing artists to town during winter time, the project Wash Up had teenagers becoming curators and thinking through the organization and planning in dialogue with the artistic direction. In this framework it is important to mention the project Compagnia di Giro (2014-2015), who organized special trips for Santarcangelo’s inhabitants to the most relevant shows, exhibitions and performance scheduled in other Italian cities.

Santarcangelo is a place where important artists have shown their work over the years and, above all, where it is possible to make space and possibility for doing and have important projects happening, two among others, the Balinese Dance Platform (2014-2015) and Azdora (2015-2016). Gazes keep changing and with them curatorial approaches and programs, but Santarcangelo remains the place allowing experimentation and openness that has been since the 70s: “a theatre that flows from a collectivity to return to collectivity” as stated by Piero Patino, artistic director of the first edition of the Festival.

Cristina Kristal Rizzo, ULTRAS sleeping dances. Courtesy Santarcangelo

“Biodiversity strives for high visibility” this is the sentence accompanying Ipernatural, the 39th edition of the Drodesera Festival organized by Centrale Fies. “The artistic context no longer disguises itself, nor accepts to hide in codified forms but rather reaffirms multiplicity and strives for high visibility. It attracts your attention. Visually, it appears as both excessive and ultra—natural, as it increases its ability to attract and defend itself, training to resist exogenous attacks. It is no longer interested in escape routes”—from the curators’ statement on this edition, as the continuation of the “Supercontinent” of the past editions. Alongside, OHT’s Little Fun Palace inhabits the Centrale’s garden, “a parasite project, a traveling pavilion aiming to produce and spread the organic nature of culture” that we met and will meet elsewhere. The caravan is set up to host lectures, dj sets and in this occasion also a pop-up bookstore curated by BRUNO. An important space that concretely contributes to this “knowledge production” recognizable in the whole festival format, bringing topics and opening discussions, both formal or informal, either outside or inside this 70s caravan.

Live works vol. 7 is a section of the Festival, a selection of projects selected through an open call and curated by Barbara Boninsegna and Simone Frangi together with Daniel Blanga Gubbay, where the selected artists attend the Free School of Performance, a period of residency at Centrale Fies and get a production budget for the performance presented during the Festival, that is seen and discussed by a board of professionals in the field of contemporary art.

Centrale Fies is not only a festival but also an important place for residency and production, that works—also and not just—very closely to the territory surrounding it. A power plant in the mountains that looks like a castle with a draw bridge, isolated but always connected, a place where you choose to arrive where you can’t possibly get by chance, yet not attended just by professionals. A context in which a lot of important companies of the Italian scene grow up overtime, that has expanded its own horizons to deal with a broader diversified liveness.

Differently from the other festival we have crossed, Short Theatre is the only one that takes place in a big city. Happening in September, it carries the typical soft vitality of the end of Summertime. Short Theatre was born in 2006 at Teatro India, a symbolic place for contemporary theatre in Rome, emblem of the city’s unattended promises (currently in a state of renaissance).

The title “Short Theatre” comes from its initial vocation of functioning as a review platform for “short pieces” and shows that didn’t fit in permanent theaters’ long runs. Although it became something else, the Festival sticked to the title, in an affective gesture that tells a lot about its identity. Short Theatre has been realized since the beginning by a close-knit collective that share the same special mission: to help the local community breath some fresh air and witness what the rest of the year does not happens in Rome, a city with complex cultural politics.

The trust toward the community and shared practices makes Short Theatre a meeting point, located in the past years in a venue that is also a symbol of a promise of the Rome’s contemporaneity, Mattatoio’s Pelanda. The subtitle of this upcoming edition will be “Visione d’insieme” (Overall gaze), that well expresses the complexity of a Festival that—through a multidisciplinary offer and careful in including the national and international artistic emergencies—tries to keep together the different souls of a city and to make them dialogue with the outside. The theatre scene, the underground Pigneto clubbers, students, performing and visual art lovers, together with people who inhabit the neighborhoods in which Short Theatre curates site-specific projects. Short Theatre is a space where to be together and dance at, to discover artworks and follow lectures and workshops.

This edition is not to be missed, with the special opening of a new location, WEGIL, that for the first two days of the Festival will be crossed by performances, talks, listening-sessions, dj sets in a continuous flow with a specific focus on post-colonial studies and decolonial feminism, followed by 7 days of dance, theatre, performance and music at the Pelanda.

Little Fun Palace at Short Theatre 2018. Courtesy Short Theatre

Undisciplined Praxis

I visited Centrale Fies for the first time in the summer of 2017. The huge building appeared in front of my eyes with a big banner displayed on its facade: “This Is Not A Castle”, it clarified in capital letters. Indeed, the hydroelectric power plant complex that houses Central Fies Art Work Space since the 90s could easily be confused for one of the many castles scattered around the mountains and valleys of the region.

As an independent centre for residencies and production of performing arts, Centrale Fies has a long history, that starts at the end of the 70s and crosses the streets of Dro. Not far from the current venue, Dro is the village that hosted the first cultural events organised by Barbara Boninsegna and Dino Sommadossi, founders and directors of the project as we know it today. A path of progressive transformation and expansion of their activities leads from the birth of Drodesera festival as a street theatre festival in 1980, to the establishment of the complex organism that inhabits the spaces of the castle-power plant nowadays, an actual cultural enterprises that works tirelessly 365 days a year. Beyond changes, what clearly emerges is the coherence of the vision guiding their action, which is strongly rooted in an idea of hospitality and community as fundamental values and essential conditions to guarantee the freedom and development of artistic research.

Dina Mimi, Is It True That Only Ants Walk In A Circle? Photo Alessandro Sala. Courtesy Centrale Fies

The banner I saw in 2017 was destroyed by a storm last April. It has been replaced by a new one, that shows the well-known sentence by Shakespeare: “To Be Or Not To Be”. When one reads it, the association to theatre and performing arts is immediate, so anyone is able to contextualize the place and its activities. But those words also contain a different kind of meaning, a political one, which brings our attention back to present times and speaks of the importance and responsibility of individual action. It reminded me that the space of art is not separated from that of real life. This is the spirit of the place, I’d say.

Among the many projects that progressively enriched the life of Centrale Fies, Live Works is a platform dedicated to live contemporary art practices. It gathers artists with various backgrounds, selected by an open call, and give them the opportunity to stay at Centrale Fies for a ten-day residency, during which they start developing a new project. At the end of the residency period, they present the works in a three-day live program, that officially inaugurates the beginning of Drodesera Performing Arts Festival. The artists can also go back to the power plant in the months that follow for a second residency phase, to continue working on their projects.

Every year 9 projects are selected, the winners of this year edition are: Nana Biluš Abaffy (AU/HR); Katerina Andreou (GR/FR); Rehema Chachage (TZ); Ndayè Kouagou (FR); Dina Mimi (PA); Magdalena Mitterhofer (IT/DE) and Astrit Ismaili (KV/NL); Ceylan Öztrük (CH/TR); Charlie Trier (DK/NL) and Cristina Kristal Rizzo (IT); Kat Válastur (GR/DE). The participating artists draw a broad geography, which expands across the five continents.

During our stay at Centrale Fies, we had the opportunity to meet Simone Frangi, who co-curates Live Works together with Barbara Boninsegna, in collaboration with Daniel Blanga Gubbay. He explained to us that Live Works was born in 2013 from the ashes of the Premio Internazionale della Performance, a national award dedicated to performance art, organized by Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea of Trento together with Centrale Fies, in the years between 2005 and 2008. It is the urgency to fill a void that motivates the creation of the project: the lack of a space and a focus dedicated to investigation and promotion of performance art and live art practices in Italy. The choice of a name, Live Works, able to embrace various kind of researches, reveals the specific intention of the curators, that is the aim to deepen and broaden the concept of performance art, beyond the constraints of any existing classification or category. First barrier to be dismantled, that which separates performance art, as a practice belonging to the realm of visual art, from performing arts and theatre. This purpose has a specific meaning and relevance in the frame of Centrale Fies, it reconnects with and develops an attitude that has characterized the work of Barbara and Dino for years. They have always tried to break down the distances dividing distinct artistic fields and to create a space for meeting and experimentation. Since the beginning Drodesera Festival has hosted artists from both theatre and visual art fields, and when the Fies Factory project was launched in 2007, the roster of artists who joined it included Anagoor, who won the Silver Lion at Venice Theatre Biennial in 2018, as well as Francesca Grilli, one of the artists exhibiting in the Italian Pavilion at Venice Art Biennial 2013.

As stated by the curators, Live Works questions “the concreteness of performance in the real world, investigating the double nature of LIVE—in person and alive—highlighting those moments in which performance integrates with the dynamics of life.” This will to underline the connection art/life and, consequently, to test the possibility for art to actually relate to the life of a community, resonates in my head and makes me think of the golden age of performance art in the 60s and 70s. Those years saw the incursion of art into life and, vice versa, of life into art. The political commitment underpinning the practice of many artists was a decisive factor for the birth of a “new aesthetic, common to different artistic disciplines that shifted the focus from sight to touch, from the rational to the sensitive, from the discrete to the continuous, from representation to life.”

Astrit Ismaili and Magdalena Mitterhofer, Pink Muscle. Photo Alessandro Sala. Courtesy Centrale Fies

Breaking with tradition meant first of all tearing down the barriers that separated the arts. The movement of interaction between visual arts, theater, music, poetry, video and cinema which animated that period, opened a way that had never been taken before, and gave life to new hybrid art forms. What happened in those and the following years is already history. Problem is that translating life into history always implies some sacrifice. Books and manuals usually tell the story of separate traditions for separate art fields and disciplines, but today, even more than yesterday, distinguishing from a formal point of view a performance by a visual artist from one by a choreographer or by a theatre company, is often tricky. Researches, influences and trajectories have multiplied and intertwined over the years. Artists today have even overcome the concept of interdisciplinarity, arriving to a new condition that have been defined as post-disciplinarity by Eva Neklyaeva and Lisa Gilardino, artistic directors of another important performing arts festival in Italy, Santarcangelo dei Teatri Festival. According to their vision, the post-disciplinary approach has abandoned the reference point of the discipline, or better, has made it superfluous. Disciplines are no longer the space of departure or arrival, because the urgency of communication is the new drive that pushes artists to appropriate multiple practices at once.

Obviously, there are still artists who align their steps along the path of a certain discipline and choose to operate in a more canonic way, but an increasing number of artists proceed on independent and tangential directions, breaking rules and categories. These kind of practices are to be found at Live Works.

In this regard, some words pronounced by Alessandro Sciarroni after winning the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at this year Venice Dance Biennial are significant. He has taken part in Drodesera Festival several times, and in 2017 Centrale Fies decided to present again his first work, Your girl, ten years after its creation. Sciarroni said, responding to the criticisms of those who judged his research as too eccentric in relation to dance as a discipline with a tradition and a canon, “I especially thank all those artists who understood how necessary it was to get out of the boundaries of their own discipline to tell the complexity of contemporaneity. Equally I’d also like to thank all those who have decided to stay within the boundaries of tradition and keep it alive. I would especially like to mention those who, because of their radical ideas, were excluded from the official circuit and the awards: thanks for not making compromises, not even when the public left the room or when it was said that what you did was not dance. (…) Thank you for insisting that we must study, but also that we should not grant anyone the right to tell us what to study.”

Live Works fosters hybrid researches and grounds in the awareness that performance art does not exist as a circumscribed space, it is more an erratic presence, that relates to and crosses varied artistic languages and media in its wandering. Frangi clarifies that the artists were not selected because they are interested in a particular topic or because they share a certain type of style. What they have in common is rather a working method. He uses the adjective “emergent” to qualify their research, specifying that it doesn’t refer to the artists’ age but to the experimental quality of the works.

During each evening guest performers accompany the presentation of the projects that won the open call. The guest artists are chosen and invited by the curators because they represent a model of format Live Works is interested in. Among this year guest performers, the artist duo Invernomuto presented Black Med, a research project that is also a DJ set, which investigates themes such as the use of technology, the phenomenon of migration and the possible communication between different species, through a collection of sounds and music from the Mediterranean area. Viewers can sit and read the text slides reporting the informations gathered by the artists, or they can just dance. Life is hard and then you die – part 3 by Juli Apponen is an autobiographical performance in the form of a lecture; the artist, who works as filmmaker, choreographer, performer and teacher, sits at a desk in front of the audience and tells her personal experience of transition from male to female sex. Vehicle of the Universe / constant minimal hooping is a choreography, a living installation and an erotic vision, in which one witnesses a progressive metamorphosis of the naked bodies of the artist duo Duchesses (François Chaignaud & Marie-Caroline Hominal), who continue rotating a hula hoop for 35 minutes while standing on two large cubic plinths in the semi-darkness of the room. The Otolith Group presented the video The third part of the third measure, born from an encounter with the avant-garde composer, pianist and vocalist Julius Eastman. The work, described by the artists as “an experience of watching in the key of listening”, is a powerful example of how the performative dimension can be extended into a video installation. In One pitch: birds for distortion and mouth synthesizers, experimental singer, composer and performer Sofia Jernberg explores the possibilities of the voice beyond the sounds and techniques of conventional singing.

Rehema Chachage, Scents of Identity, Ph_ Roberta Segata. Courtesy Centrale Fies

Before the guest performers, each night three of the nine projects taking part in Live Works are introduced to the public. They are not finished works, but rather a first elaboration of potential works. Nevertheless some of them already show a formal completeness and complexity, such as Hypernating by Cristina Kristal Rizzo e Charlie Laban Trier, that explores the possibilities of a narrative voice as a sensitive material. The voice evokes stories and bodies and shapes spaces halfway between the physical and the visionary, able to be inhabited by our imagination and our memories. In the darkness of the stage the bodies of the performers move with minimal gestures, manipulating technological objects, a mobile phone, a TV screen, which have lost their function to become something else. The artists physically mold visions as luminous gleams, that immediately are reabsorbed into a dark viscous matter. Pink Muscles by Astrit Ismaili e Magdalena Mitterhofer explores body politics and aesthetics through the deconstruction of the songs of singer, activist and former pornographic actress Cicciolina. The performance builds a sequence of elegant images through the use of the voices and bodies of the performers plus some scenic tools, and succeeds in addressing with an admirable delicacy a theme that is as hype as it is urgent. In Oriental Demo, Ceylan Öztrük hybridizes the performance lecture format with a real-time belly dance lesson, conducted by an Italian professional belly dance teacher. Starting from the narration of her personal experience, the artist investigates the way Western patriarchal narratives have generated a stereotyped and heteronormative view of femininity and of oriental traditions. Rehema Chachage presented Scents of identity, that is a performance but also an environment, made of simple elements: gestures, photographies, objects, smells. The artist’s action has the solemnity and temporal suspension of the ritual, and assembles together fragments that speak of the history and identity of his native country, Tanzania.

Others projects appear more evidently as initial manifestation of a broader research, that could potentially develop in various directions. Arcana Swarm, by choreographer Kat Válastur, explores the possibilities of translating an inner state into a performative condition, that is investigated through the movements and interaction of two dancers. Dina Mimi’s work, Is it true that only ants walk in a circle? is halfway between a lecture performance and a storytelling; she uses the circular movement as symbolic connector to construct an imaginary capable of containing a narration that embraces the universal from the particular. The artist tries to insert the use of her body into the performance, and breaks the frontality of the setting by walking among the public, making circular gestures. Ndayé Kouagou’s I don’t want any of this to be part of any of that plays on the raw presence of the artist in front of an audience. Kouagou proposes hints of reflection around the ambiguity of language and of enunciative positions, and attempts a work on the space through the use of his body and some basic elements, such as tape and a chair.

Some of the artists focused on exploring media and practices they had never tried before. With Zeppelin Bend Katerina Andreou tests the expressive possibilities of aerial acrobatics technique, bringing to the stage certain artistic trends and aesthetics inspired by club culture. Green Nasim by Nana Biluš Abaffy & Parvin Saljoughi takes inspiration from the figure of the Iranian youtube video artist and animal rights activist Nasim Aghdam. The artists try out the possibilities of distorting and altering the viewer’s perception through the live recording of a video camera.

While staying at Centrale Fies during the three days of Live Works, one has the feeling of taking part in an extensive open studio or in a midterm presentation of an art school. The unfinished and open state of the works let the visitors witness and be part of the ongoing creative process. This is the most important and interesting aspect of the project as a whole. In 2016 the curators decided to abandon the prize format. This allowed a redistribution of funds to benefit all the artists selected with the open call, not a single winning project. But, above all, the choice implied a change in the meaning of the residency program itself. Not being influenced by the necessity to present the best work or at least a work as complete as possible, the artists have gained a new and precious freedom of research and experimentation. Free School of Performance is the name of the ten-day residency that precedes the public presentations, and indeed an actual pedagogical program is offered to the artists. The program alternates moments of individual research with collective critical sessions, studio visits and reading groups, and the participants are followed not only by the curators but also by a board of international professionals. They are provided with all technical facilities and have the opportunity to constantly discuss with the staff of technicians, who, as pointed out by Frangi, is the first real curator of the projects. This community dimension and the constant sharing of knowledge and practices generates a horizontal and anti-authoritarian model of learning.

Live Works shows itself as a safe space where art can escape the obligatory production mechanisms imposed by the market even on intellectual work. It proposes a model of hospitality and sustainability of artistic research, and an idea of art also as social practice. In some aspects this model is linked to an important tradition of artistic pedagogical institutions, that starts almost a century ago with some cutting-edge teaching experiments, such as the Bauhaus and or the Black Mountain College. I would like to close these considerations by quoting a few words of two of the protagonists of those extraordinary experiences, which seem to fit well with what we are talking about. “Our central and consistent effort is to teach a method, not content, to emphasize process, not results,” said John Andrew Rice, founder and first rector of Black Mountain College. Instead Josef Alberts, who taught at Bauhaus and after the closure of the school under Nazi regime moved to the US, where he continued teaching at Black Mountain, once said “we do not always create works of art, but rather experiments. It’s not our intention to fill museums, we are a gathering experience.”

Studio Visit, Photo Roberta Segata per Centrale Fies. Courtesy Centrale Fies

Learning by Doing

This was my first time at Centrale Fies, my reflections around what this place does and what this place is may sound a bit naive, considered the fact that many calls this place home. Still, I had the privilege to enjoy with a pristine curiosity that made me discover this place at once. Centrale Fies Art work Space is an independent centre for residencies and the production of contemporary performing arts, currently located in a still partially active hydroelectric power plant, in Dro, in the Trento province in Northern Italy. The cultural enterprise that Centrale Fies is now is the result of almost forty years of history, lived by the founders Barbara Boninsegna and Dino Sommadossi (with collaborators and friends). Before we romanticize about its past, Fies today is first of all a hosting facility that welcomes and nourishes experimental practices, encourages research and facilitates production. In contrast with many similar art institutions or facilities, Fies conserves this allure of being profoundly part of the surrounding territory. Probably because the partly active power plant is still taking in water and generating electricity, but also and mostly because the project never left Dro, but rather took the world in there, generating a less literal energy, nonetheless as powerful.

Indeed Centrale Fies works as a reservoir, especially the impression I got from this 7th edition of Live Works is of a power plant turning matter into energy. The resident artists presented draft pieces that altogether gave an overview of the trends and tendencies of contemporary performative arts, from lecture performance to dance. The unfinishedness of the works reveals the pedagogical drive of the platform; initially a competition, today an expanded idea of award, with no professional jury nor a winner, the idea behind Live Works is of a long-term activity. The selected projects have a first 10 days residency, that includes curatorial support, access and guidance through all technical facilities and a production fee. The program provides a theoretical framework—the Free School of Performance, with studio visits, critical sessions, reading groups, discussions around specific themes to redefine the very concept of performance, and informal encounters to foster the production of each project.

Studio Visit, Photo Roberta Segata per Centrale Fies. Courtesy Centrale Fies

Live Works is the embryonic stage of the hypernatural entity that Centrale Fies is at large. In the words of curator Simone Frangi, the focus is not on specific theme nor medium specificity, but rather in offering and providing actual research tools to artists and their practices. The initial intention since the first edition in 2013 was to give space to performative arts, as for once there was a lack in the Italian artistic landscape, but also performance has usually been considered somehow ancillary compared to other disciplines. So to go countercurrent and revalue the matter, the idea was to build a proper performance centre that could expand and deepen the performative aspects of the artistic practice; a residency program conceived on the premises of hospitality and sustainability, founding principles of Centrale Fies’ overall mission. Although bringing in new practices, the breaking point of Live Works was a certain skepticism towards innovation—it is not always about seeing something new, as performance art is already something that breaks with tradition, that navigates in between disciplines and labels and resists stereotypes—while also an attempt to offer something other than the usual Eurocentric aesthetics and trends.

Live Works is a platform meant as a safe space, even in the moment of presentation allows the existence and sharing of this unstable material that contaminates the whole Drodesera festival, and protects the artistic product in its potential for development as an open chance to understand otherwise. When talking about the potential counter pedagogical effect on the Live Works’ audience, Frangi quotes American art critic and activist Craig Owens saying “give Lacan to the students and they’ll know what to do with it.”

Katerina Andreou, Zeppelin Bend. Photo Alessandro Sala. Courtesy Centrale Fies

This 7th edition of Live Works opens with a lecture performance by Palestinian artist Dina Mimi who asks through circular movements, “how do we begin to observe the madness that consumes the mind? If to navigate is to know the place, going in circles make us go mad.” A brief excursus made of visual and textual suggestions, unfolding the beginning of a promising research.

Choreographer and music maker Katerina Andreou invites her friend Ioanna to join in—“in a desire not to double me but cut me in half”—for a dancing performance going from birds chirping to boxing and techno hardcore, aerial dance with hanging bodies and mics, in a splitting of bodies that at times give us the illusion to be the same body.

The lecture performance Ceylan Öztrük unfolds and stresses upon the connection between heteronormativity, especially the female body and orientalism. The artist keeps the format of the lesson, accepting its unfinished character, and as she bellydances with the guidance of a local oriental dance teacher, doesn’t disguise the hesitation and embarrassment. Through this process of (weirdly exotic) imitation we witness a westernized body being guided by a orientalized body in an astonishingly effective mirror effect.

The first night is wrapped up by the guest performed Invernomuto, and their work Blackmed, an almost three hours playlist of music collected throughout and around the mediterranean area, that necessarily puts compelling topics at stake, such as migration and respective influences, technology and interspecies communication, thus turns the Mediterranean sea into a connector and container instead of a border.

Ceylan Öztrük, Oriental Demo. Photo Alessandro Sala. Courtesy Centrale Fies

Rehema Chachage opens the second day with a deep sensory experience, rich of suggestions given by simple gestures and symbolic practices like suing a cloth and lighting up incense. Chachage delivers stories through rituals, demonstrating the significance of oral and alternative histories, and delicately takes us someplace else.

A complete different vibe and approach in Astrid Ismaili & Magdalena Mitterhofer tribute to Cicciolina’s oeuvre, employing soft and body politics, the “operetta” is beautifully choreographed and makes great use of voice, props and stage, in a continuous outfit change of which the most valuable costume is the bare body.

Nana Biluš & Parvin Saljoughi’s piece is a multimediatic choreographic work that makes use of different technologies, like video, lights, and screens, inspired by the story of youtube video artist Nasim Aghdam. “Dictatorship exists in all countries, just in a different form” got stuck in my head, among the almost paranoid succession of live videos and projections.

First of the two guest performers of the evening, Juli Apponen’s Life is hard and then you die – part 3 demands us to endure a story of suffering, yet told in an extremely bold yet humble way, capable of turning pain and trauma into value. By telling difficult experiences, the artist brings forward issues of identity and generously offers a way through by sharing.

Mesmerizingly simple, Hominal & Chaignaud DUCHESSES_vehicle of the Universe / constant minimal hooping, is literally made of two naked bodies on two pedestals hula hooping. No added sound but the dancers’ growing moaninga, as the rhythm speeds up. In the hypnotic movement, many images shape in our eyes—I guess it becomes a very subjective experience, if one gives themselves to the meditation: classical sculptures, renaissance paintings, orbiting planets in climax.

On the third and final day, french artist, writer and music producer Ndayé Kouagou enters the scene in feathered trousers, and tapes himself a stage to recite I don’t want any of this to be part of any of that, a monologue that leaves space to ambiguity—“If I’m being honest I’m as confused as you”—as eventually life is a path to find the right questions, isn’t it?

As guest performers, The Otolith Group has sent their movie The Third Part of the Third Measure (2017), on the militant minimalism and black radical aesthetic of avant-garde composer, pianist and vocalist Julius Eastman. Eastman’s composition are accompanied by excerpts of Eastman’s speech, interpreted by poet Dante Micheaux and artist Elaine Mitchener. What the video doesn’t say is worth a further research.

The dancing piece choreographed by Kat Válastur is enriched by the light effect coming in the room through the windows, as if it was a setting sun. The two dancers go from ecstatic joy to physical collapse, rise and fall, continuously—“they found them covered with stars”—meet and separate, bleed and cheer, trapped in their own performative condition.

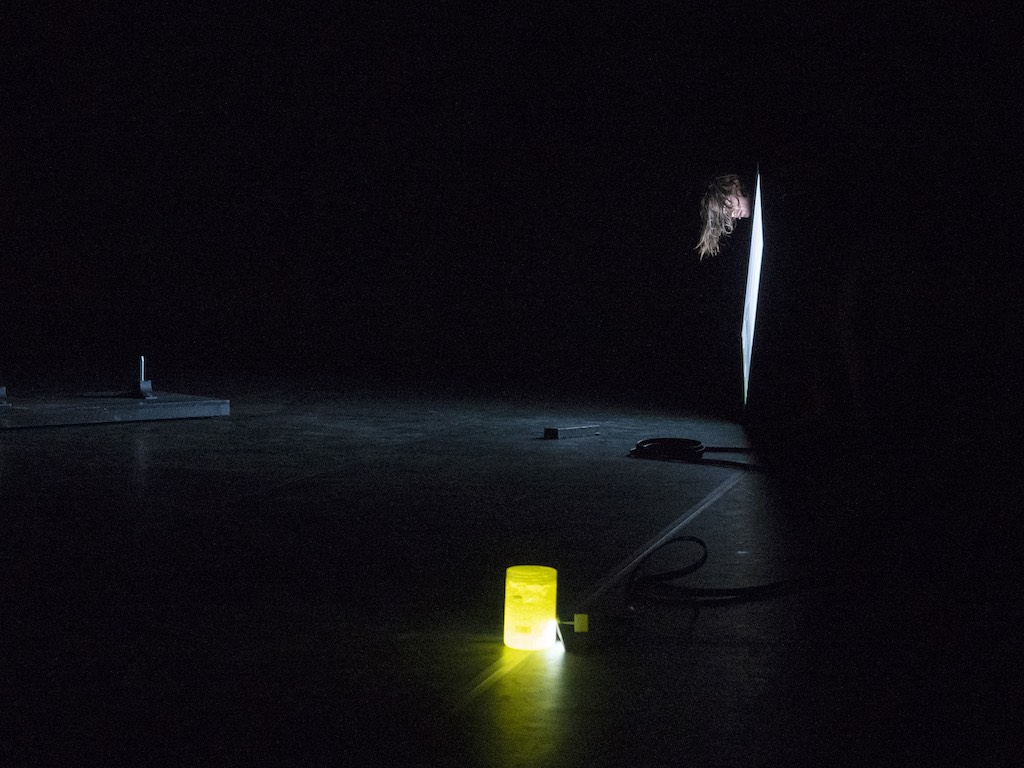

Cristina Kristal Rizzo & Charlie Laban Trier welcome us prepared for a completely dark environment, in which lights and (broken) screens become props for the slow moves of a whispering body that tells a story that sounds at times like a poem and at times like a song, maybe a love song, for sure an intimate space.

The other guest performer, Swedish experimental singer, composer, improviser Sofia Jernberg closes these incredible three days with an as much incredible performance. Difficult and diminishing to try to describe in words what Jernberg does with her voice, through non verbal vocalizing, split tone, pitchless and distorted singing she for sure took us to places; elsewhere and otherwise, out of ourselves, floating on her deep sounds.

Sofia Jernberg, One Pitch: Birds For Distortion And Mouth Synthesizers. Photo Alessandro Sala. Courtesy Centrale Fies

All this was Live Works, an experience that by means of hospitality, brings the world to Dro and takes Dro out to the world. When you get to Centrale Fies—like me for the first time, you start wondering how such a place came to exist. For those of you who don’t know the story, it’s with great pleasure that I report it here, as I perceived Fies as a place that remained true to its initial ideal, that of the people who made it and still run it.

The project, launched in 1999 by Barbara Boninsegna and Dino Sommadossi with the Cooperativa il Gaviale on the experience of drodesera festival (born in 1980), is today a proper cultural enterprise. Yet, the whole story of these 39 years is quite peculiar, especially when heard by Dino’s personal recounting, with whom we had the pleasure to sit down for a while. In 1979, Dino takes the lead of the local library in Dro, and considered the social turmoil of that historical moment and the general desire for change, the library immediately becomes something else, starting with modest musical activities and a small festival. Then the referendum on abortion comes and Barbara distributes leaflets in favor of the law. As this happens then in the only gathering space available at the time, the church oratory, the priest excommunicate them and forbids the use of the room. Dino says “unconsciously the priest is the one who founded the festival” as the immediate reaction is to take the streets.

The events move to the square, in the alleys, to the woods, by the river. Any place surrounding Dro is a potential stage—“as we did not have a theatre we used everything.” Street theatre, circus, shows, concerts, dance, sparkling wine and street food. Drodesera becomes the place of the night refined encounter. First fonds start to appear and turn the festival into something more stable, while with other theatre festivals a network is created “Viaggio in Italia” (travel through Italy), that gives Drodesera the imagination to expand and look outside Dro. In the 90s, the festival slowly approaches the opportunity to use the hydroelectric central, piece by piece, it conquers room by room, cleaning up the space and restoring it, and turning it into what is today. The restoration preserves the historical structure of the power plant, and turns it into a place for “thought, work, residency and hospitality.” The festival is for the summer and the rest of the year, the place is open for production, research and creation.

The artists come and Centrale Fies sustains them, literally transform their material into energy, converges and extract the transformative creative power. When the situation becomes more stable, the decision is made to give space to emerging artists, with no obligation to produce. For three years, since 1996, the first round of artists is given the space to make, think and create financed and welcomed by the centre—the factory. A model of sustainability that allows the artists to work without stress, and produce some of the pieces that made the history of performing arts and theatre. Meanwhile, the factory opens up also to the European network, to which Fies adheres at the condition to keep its own model.

Since the beginning the ambition is to nourish independent practices, that would go and stand against the conventional system of production and entertainment, “we started with the intention to make the revolution (…) and we remained attached to this place, because we managed to change it somehow.” Performance art is in itself an inherently transformative practice, both for the people who make it and for those who witness it. In the general precariousness of artistic production, the desire for change is often the drive behind making—as “culture is supposed to ignite and break.” The creation of a safe space is a founding step towards freedom of expression and formulation. “We learned by doing”—as giving the space to artist for this doing guarantees an ongoing open space for learning, of a double vector that brings the world to Dro and opens Dro and the Italian artistic scene to the world.