Dear Grandma, Did You Know?

Laure Prouvost’s “Ohmmm age Oma je ohomma mama” at Kunsthalle Wien

Curated by Carolina Nöbauer, program dramaturg of the cultural festival Wiener Festwochen, the exhibition Ohmmm age Oma je Ohomma mama is the first solo exhibition of the French artist Laure Prouvost in Austria on view at Kunsthalle Wien until October 2023.

“Oma, did you know we can play

music so loud that the sound can

reach the other side of a city and give

us goosebumps?”

The exhibition presented at the Kunsthalle in Wien is a multimedia, composite, and layered letter that the French artist Laure Prouvost dedicates to the figure of the grandmother, starting from the origin, the small Paleolithic statue of Willendorf Venus, discovered in Austria and exhibited at the Naturhistorisches Museum of Wien.

This show could be seen as the counterpart extension of the previous exhibition entitled GDM – Grand Dad’s Visitor Centre, shown in 2016 at Pirelli Hangar Bicocca in Milan, in which Prouvost created a museum dedicated to his grandfather—a supposed artist—who passed away.

She conceived the aisles of the Hangar as multiple scenarios, capsules composed of small domestic settings and large screens. On one of these, Wantee (2013), his grandfather’s works are projected, sculptures that became part of Prouvost and his grandmother’s daily life after his absence.

If in the exhibition shown in Milan, the French artist’s attempt is to “musealize” his grandfather, through a chaotic mix of images from mass culture and the evocation of private settings, in the exhibition curated by Carolina Nöbauer at the Kunsthalle in Wien, Prouvost—always starting by the same matrix—tries to depict a mixed media portrait that restores the figure of the Grandmother by intersecting private narratives with social ones, returning an atlas of 130 “sisters” composed of women who belong to the artist’s private life, but also those who inspired her, continuing to draw from some of her major issues, such as language, seen as a somewhat disjointed, childlike practice, given by the mixture of the two languages spoken by the artist, French and English. Language acts as a bridge for new linguistic formulations that produce shifts of meaning and tender misunderstandings, contributing to another main theme: the construction of stories and their stratified transmission between past and future generations.

The title of the exhibition “Ohmmm age Oma je ohomma mama” is a clear example of Prouvost’s artistic practice: when read and then repeated aloud, it evokes the mantra “Ohmmm” encouraging meditation, followed by “age”’ in English, which contributes to the word “homage”’ and then “Oma” meaning grandmother in German. [1] The linguistic resemblance of these three languages creates universal recognition, forming an “Homage to Oma’’, the grandmother Prouvost addresses in the exhibition.

The homage is composed of a heterogeneity of elements: objects, films, sounds, and lights that are intermittently activated, guiding the viewer through the dark space on the ground floor of the Kunsthalle. Upon entering the exhibition, a group of six drum cymbals mounted on vertical supports intermittently activated by an electrical impulse at unexpected intervals. The result of Hi Her Garden (2023) is a vibrant and high-pitched sound, recalling an initiatory, yet ancestral dimension. This surprising element jolts the viewer as he approaches the musical instruments, bringing back the playfulness inherent in Prouvost’s artistic practice. Upon entering the space, visitors find themselves immersed in a-temporal darkness. Here too, a capsule awaits—a large metal mesh structure that immediately exudes coziness, serving as a protective nest. This nest offers a place to watch the first video screen that stands between the visitor and the works arranged in the space, preventing an overall view. The first film Here Her Heart Hovers (2023) emanates vibrations that branch out into the bodies of the viewers crouching in the nest and gradually into the room itself. It becomes clear that Prouvost has designed the exhibition as a pulsating, expanding cosmos.

At the center of the screen, a group of women are filmed sitting in a circle, reminiscent of their ancestor’s intent on telling stories, in an intimate and private dimension. Then, a shadow of a gender-undefined child addresses Oma, the grandmother, with tender questions that all begin with—“Oma did you know?” echoing the way a child shares new acquired knowledge with an adult, depicting the affectionate relationship between grandmother and granddaughter.

Through childlike and naive language, the artist engages with Oma and the viewer, although the themes are no longer those of childhood; they express the profound turmoil of our contemporary society, such as globalization, women emancipation, land consumption and climate change—“Oma did you know that now we have tap water in our homes, we eat avocados coming from the other side of the planet, did you know we threw each of us an average one ton of rubbish each year?”

After a series of questions, the video begins to “break through” the fourth wall and engage with the surrounding space. It activates the lights behind it, guiding the visitor to go beyond the screen. The video acts as a portal, and as visitors cross it like the child they become the shadows that new visitors will see scrolling across the front of the screen. The voice, previously concentrated on the speakers above the screen, starts to expand and pervade the surroundings along with the lights. These resembling theatrical highlights, illuminate objects hanging from the ceiling and the objects appear awakened and begin to tell their stories, intersecting various storylines within the exhibition.

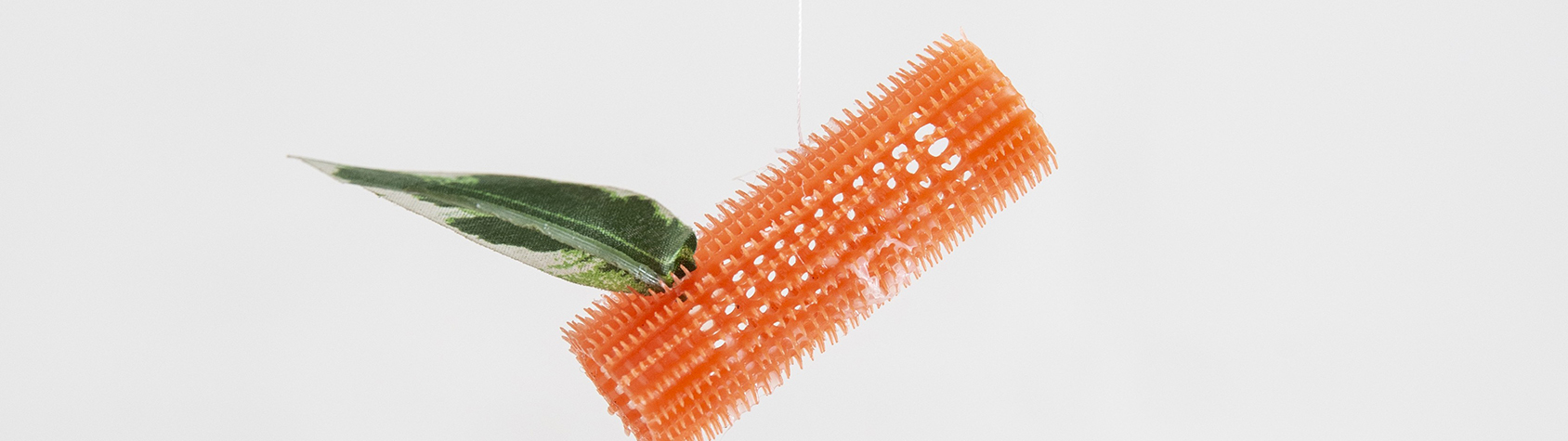

The hanging installations above the piles of sand filled with objects evoke Bruno Munari’s mobiles—once again, drawing on childlike imagery—an example is Moving Her (2023), which encourages intuitive and affective engagement. This approach mirrors our attempt as a child to fill moments of boredom by collecting everyday objects found half-submerged on the shoreline: old lighters, tampon applicators, empty medicine blisters, a curler. These objects are combined with naturalistic elements like pebbles with unique shapes, bird feathers, in unconventional assemblages. These compositions carry personal and intimate meanings, reminiscent of tiny, ephemeral childhood treasures, destined to be abandoned again after a day of playing.

As in the solo exhibition presented in 2019 at the French pavilion of the Venice Art Biennial Deep see blue surrounding you / Voi ce bleu profound te fondre, small glass and ceramic objects return, this time carrying more explicit meanings. Each object pays homage to the “grandmothers” of history, who are pioneers of social movements, scientific discoveries, and significant contributions to cinema and art: another “net-nest” place the visitor in front of Gathering Ho Ma, The Glaneuse (2023), where a pile of wood and glass sticks creates an improvised bonfire, surrounded by a series of objects. The small bonfire induces a feeling of rest, of pausing in an environment that the artist makes comfortable and “warm”. Prouvost recreates the cave’s atmosphere present in the first film we encountered; this time we are no longer the spectators but an active part of the story, in which hanging objects play the role of our interlocutors. One of them is a potato laying on the ground, it seems roasted by the heat spread by the fire on the sand, but it is also an homage to the French film director Agnès Varda, who was obsessed with the tuber. Provost’s method can be approached as one of the Varda’s subjects depicted in the documentary, Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, where as a modern gleaner wanders in search of relationships, food, collecting junk objects, such as mobile phones that we find hanging or placed along the exhibition route, they were used as instruments of a ritual in the first video we encountered, but as we walk through we find them again with a broken screen or next to a still image. They seem like fossils, consumer products now in disuse, positioned next to a pair of ceramic slippers, fragile reproductions of those that belonged to the grandmother, relics of the private life of the artist.

Sound also plays a crucial role, as the result of a collaboration between the artist and the composer Elisabeth Schimana (1958), considered a pioneer of electronic music in Austria. The entire exhibition is a continuum made up of whispers, verses and small phrases recited by a female voice, fluttering among the installations like dragonflies. Schimana becomes another “grandmother” to whom Prouvost pays homage.

The set of portraits that Prouvost collects and reformulates within the exhibition leads to an archetypal genealogy of the Grandma. The ethereal grandmother embodies other grandmothers from the past, spanning from antiquity to recent history. These portraits appear as pathosformels, lying on piles of sand arranged along the exhibition route. The 130 women range from the Venus of Willendorf, considered the progenitor of all grandmothers to activist Rosa Parks, Agnes Varda, to the mathematician Ada Lovelace: their stories intertwine with those of female figures in the artist’s private life, creating an elective and enlarged family nucleus, that span outside the biological family.

In this confusing and affectionate overabundance of grandmothers, through simple everyday objects and oral storytelling Prouvost manages to make people identify with her narrative, where memories related to our grandmothers become hers and vice versa, until it becomes an inclusive and indefinite stream of knowledge, continuously expanding, inviting us to build our own atlas, in seeking and identify our personal Venuses of our daily life and paying homage to them.

[1] Carolina Nöbauer’s introduction to the exhibition.