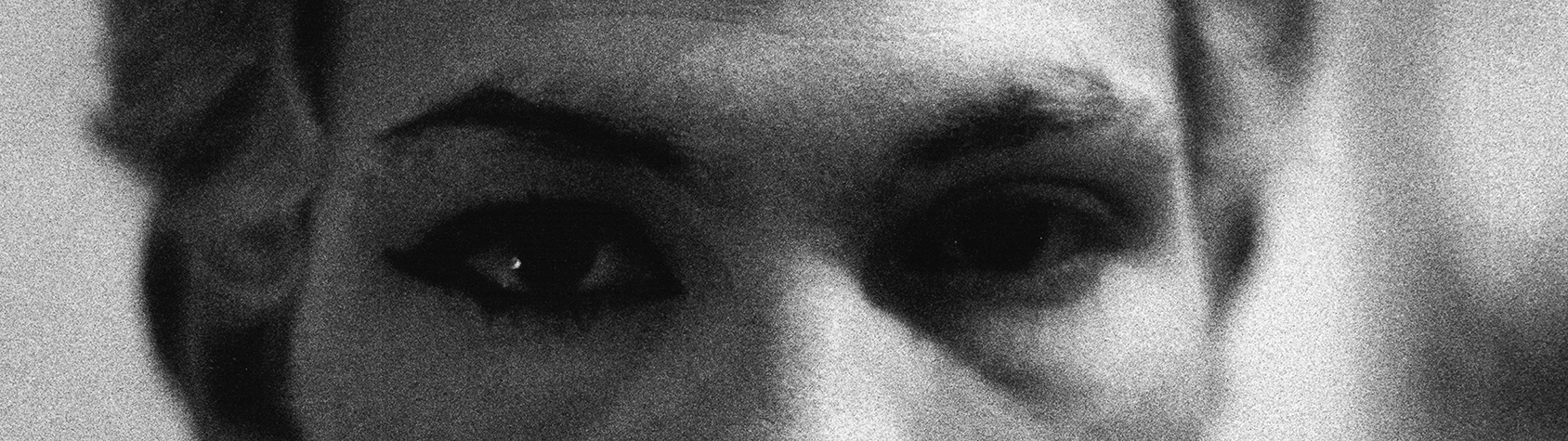

Contemporary Queer Carmi

Lisetta Carmi worked as a photographer from 1960 to 1978, capturing her contemporary minor histories

Currently on view at Museo di Roma in Trastevere, an anthological exhibition, curated by Giovanni Battista Martini in collaboration with Zètema Progetto Cultura, retraces the intense professional life of the Genoese photographer Lisetta Carmi, who has been said to have lived five different lives. This is the first public exhibition in Rome mainly dedicated to the second life of the over ninety-year-old artist, displaying an overview of her life and photographic oeuvre.

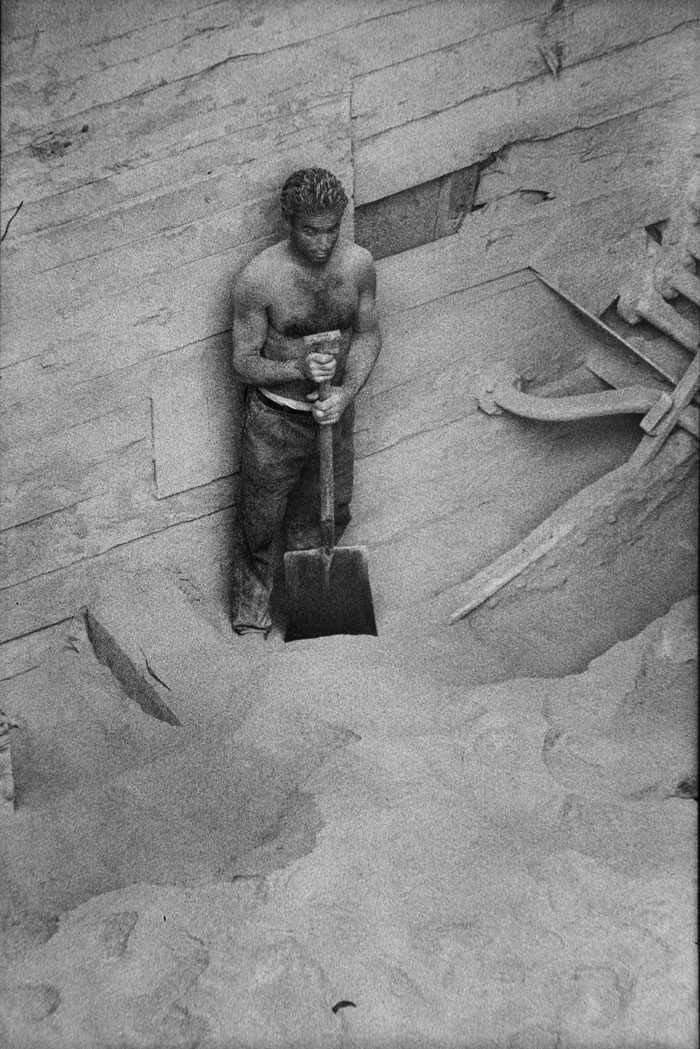

We begin from the harbor of Genova. In 1964, Lisetta Carmi was asked to capture the working conditions of the dockworkers, in a time when the access to the dockyard was strictly forbidden to anyone, especially women. Back then, Lisetta Carmi was forty years old, photographing only since four, and already living her second life—although she was not aware yet that she would have been living five lives. Her first life was completely dedicated to music, as a very talented pianist Lisetta toured for concerts and worked as a piano teacher for 22 years, until one day, on 30 June 1960, her piano master Alfredo They didn’t allow her to attend an anti-fascist strike—called for the same dockworkers she was going to photograph four years after—because she would have run the risk to break her arm and ruin her career. Already frustrated by the very individualistic nature of her occupation, Lisetta quit playing piano the day after, because, she says “if my hands are more important than the rest of mankind, then I’d rather quit.” Shortly after, she decided to get herself a camera and follow her ethnomusicologist friend Leo Levi in a trip to record the chants of a Jewish community in San Nicandro Garganico, in Puglia. As she got back to Genova she developed the three rolls she had been shooting and decided to become a photographer. Her brother Eugenio was already experienced with photography, so he suggested her to visit his photographer friend Kurt Blum in Bern. “Look always at what’s in the background”—Blum told her. During her second life as photographer, that line sticked to Lisetta’s mind the whole time. Beside and beyond the formal approach of Lisetta’s gaze, her attitude and peculiar attention towards marginal situations and characters, minorities, underground and funeral architectures are somehow recurrently taking us back to a social background that would usually remain non-portrayed, yet is definitely and absolutely central in her oeuvre. Immediately visible from the first photographic series in the exhibition, Carmi’s shots are a critique, or to use her own words they “give voice to those who aren’t allowed to speak.”

Lisetta Carmi, Il Porto, Genova, 1964. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Lisetta Carmi, Italsider, Genova, 1964ca. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

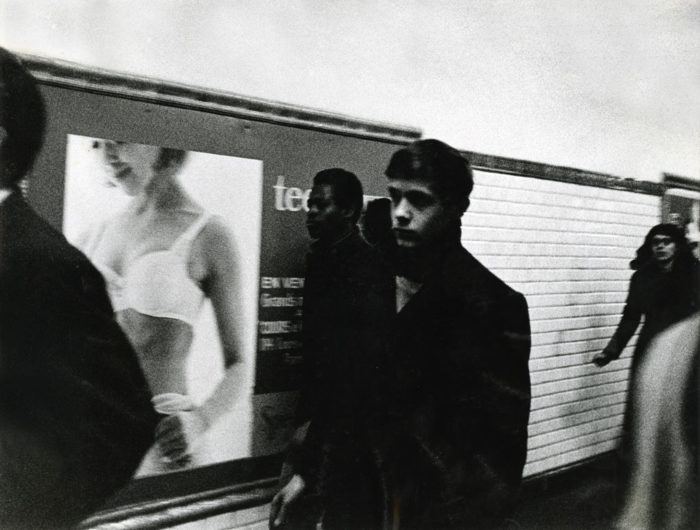

In the first photos, the dockworkers are in rags, shoveling phosphates and moving an economy of heavy goods. The images that Lisetta gives back are overwhelming of dignity, and somehow gratitude. The fact that she comes from a “good family” contributes for sure to some sort of exoticism in regards to the subjects she photographs, but her interest seems genuine and she does not tend to fetishize them. At the end of the alley, Lisetta’s own voice resonates declaring she is an anti-conformist. In the challenged position of the viewer, it is easy to recognize that the first one who’s looking for challenges is the artist herself. It is more a matter of truth, than taste. The questions that are posed to the viewer were at first called on herself. And the issues are bold and still—more than ever—contemporary: class, gender, inclusion. The anti-conformist territories that are explored depict nothing antagonist, but rather other constitutive grounds of reality, which she seems to be willing to make as legit as what is considered to be a “conventional scene.” Like in the Metropolitain series, the obsessive focus to the Parisian underground shows a life happening below the city surface, and could that ever be considered less of a city or less of a life? Or in the Staglieno cemetery photographs titled Erotism and Authoritarianism in Staglieno, where erotics and politics are placed under a magnifying lens, Carmi is resuming a lover’s discourse into an otherwise funeral and silent corner. A lover’s discourse that puts patriarchy at stake.

Lisetta Carmi, Il Porto, Genova, 1964. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Series after series, I did not feel it was about courage—as it might be said of such an independent woman, back in the days—but I rather felt any choice was driven by a genuine fascination, curiosity and necessity. A compelling aspect of Carmi’s practice is indeed her project-based methodology. She was not simply going out in the world looking for shots, but when she was taking her camera she already knew what she was looking for. Sometimes, the “project” lasted for a few days, some other times for years. Several projects ended up being books, some others book maquettes, some others remained films in rolls. Nevertheless, every picture still radiates a manifest desire.

Lisetta Carmi, La Metropolitana, Parigi, 1965. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Lisetta Carmi, La Metropolitana, Parigi, 1965. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

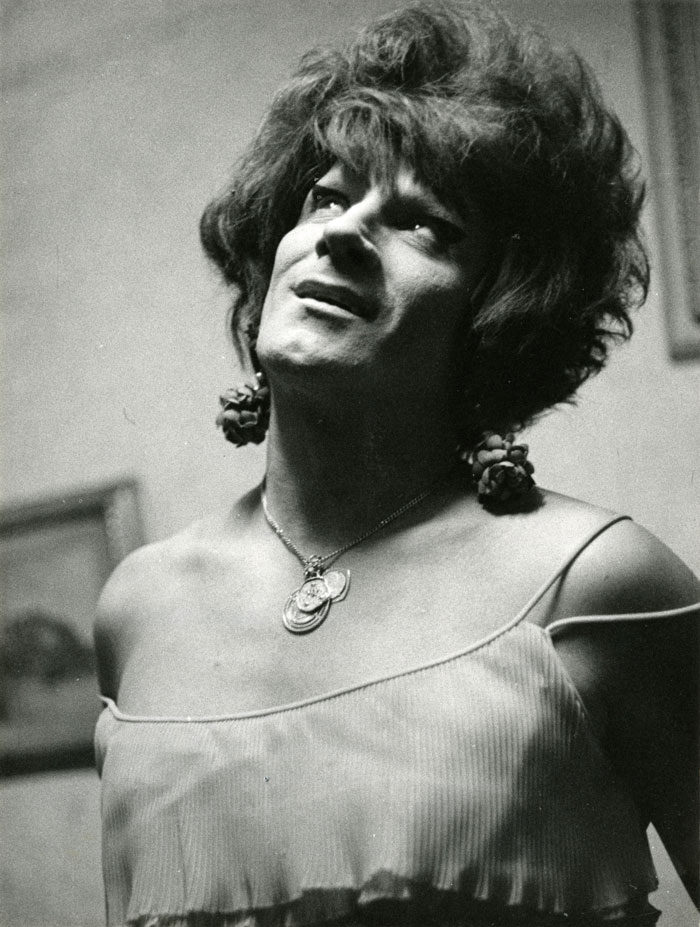

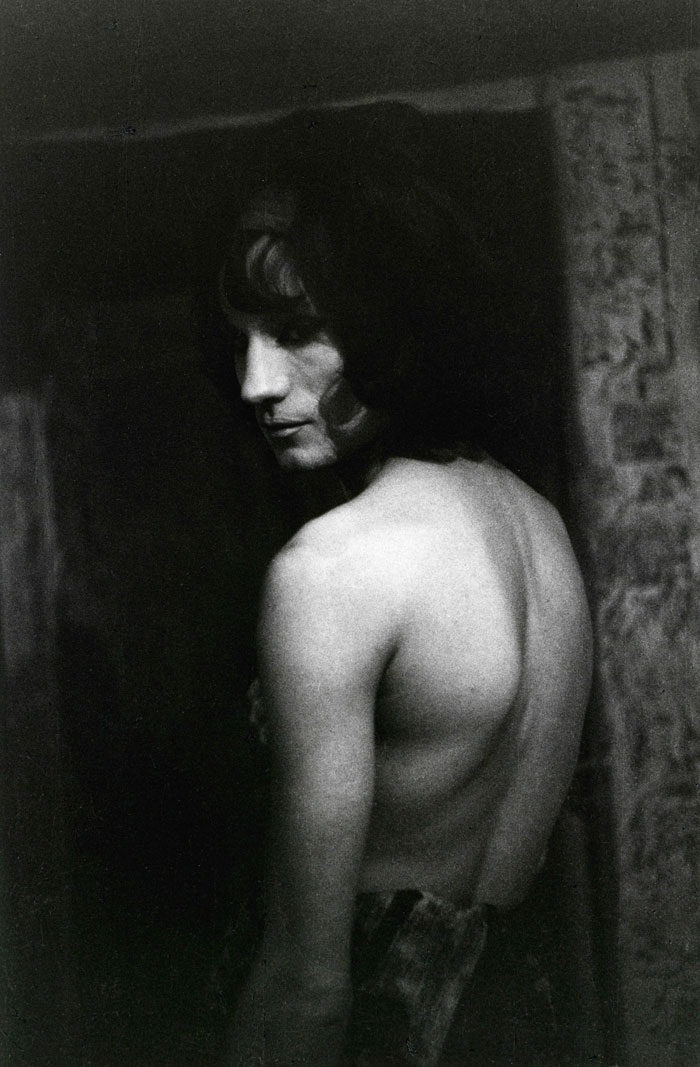

As the exhibition unfolds, we are lead to Piadena to meet the pedagogue Mario Lodi and the folk musicians Duo di Piadena; to Orgosolo (Sardinia), and then to Sicily where she could fluidly narrate the local society under the pretext of water. Within the umbrella of the project titled Acque di Sicilia (1977), waters of Sicily—a research on the water resources of the island, commissioned by Dalmine and with texts by Leonardo Sciascia—the sub-series on women, men, landscapes and funerary notices give us a much more complex anthropological account than the assignment was initially meant to convey. The most water-related aspect of this work is surely the fluidity of Lisetta’s language, and the inherent feminism of her approach. A feminism not necessarily outspoken nor declared, which is even more perceivable on her most known work I Travestiti (1972): a series on the transvestites’ community of Genova, which also became a book, with a much more controversial history when compared to Acque di Sicilia. Again, it is not just an exotic fascination that lead Lisetta to approach and photograph her subjects but rather an affiliation. Lisetta Carmi never felt comfortable with the female role society had destined to her, and never really pretended to play it. Beyond sexuality and gender, the independent strength of her personality is visible in the confidence invested in her life style. The impression is that everything is a voyage, whether she travels from one life to another, or to another land, or she is approaching a world yet unknown—a religion or a community, with curiosity and openness, she is never being sensationalist. She was looking for beauty and found it. I had to think of Virginia Woolf’s Room of One’s Own, “…I am talking of the common life which is the real life and not of the little separate lives which we live as individuals—and have five hundred a year each of us and rooms of our own; if we have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think; if we escape a little from the common sitting-room and see human beings not always in their relation to each other but in relation to reality; and the sky, too, and the trees or whatever it may be in themselves.”

Lisetta Carmi, Sicilia, Piazza Armerina, 1976. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Although the book I Travestiti was received as controversial when published and already had encountered many difficulties before even going to print, these specific portraits are more perceivably about friendship, rather than a mere anthropological study. Today a collector item, the book includes a series of interviews conducted by Lisetta and her psychoanalyst friend Elvio Fachinelli. In her video interview, she recounts the story, that once she left Fachinelli to do the interviews alone and he got teased so much by the ladies, he had to beg her to come back. In the book, he wrote that the photos were born within an in-depth relationship of complicity, and they were tearing the label and brought diversities on the surface. Looking at the photos, I feel it’s more about inclusion than difference. I feel she felt home.

Lisetta Carmi, I Travestiti, La Gitana,1968. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Lisetta Carmi, I Travestiti, Dalida, 1965-1967. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Anyway, at the time the book topic was so tough that the first publisher renounced, and when it got finally printed (funded by a friend), no bookstore really felt like having it on display. Only the bookstore Remo Croce in Rome bought one hundred copies and organized a presentation with writer Dacia Maraini, anthropologist Luigi Lombardi di Satriani and poet Dario Bellezza. In the audience, there was also Alberto Moravia. Still, more than 3000 copies laid unsold at the typography, and if writer Barbara Alberti wouldn’t have rescued them all, they would have been disposed of. Eventually, Barbara Alberti gifted all her copies away, Lisetta always refused to reprint the edition, and the book became a cult object.

Among other portraits, the Ezra Pound series lingers instead on the unspoken, respectful of the blurred mental condition of the subject: a silent photography, suspended in the incommunicability, where these few instants of contact are perceived as extremely valuable, as if the gaze of the poet could contain more than any of his verses. Again the background sustains the object: a background that is not composed nor framed into stereotypes, but rather organic and fateful.

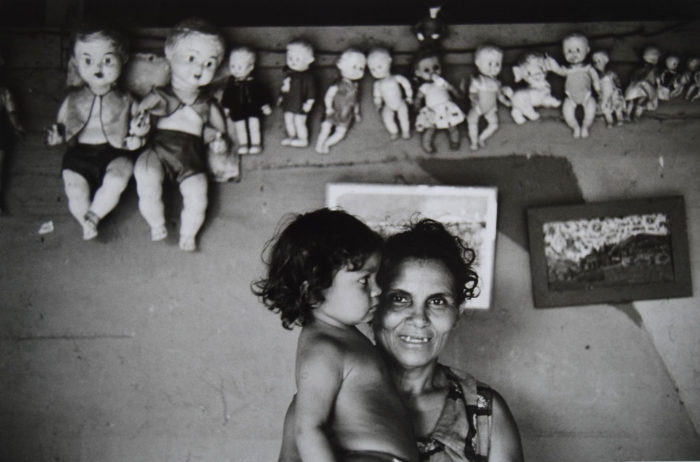

Lisetta Carmi, Venezuela, Venditrice di Bambole, 1969. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Lisetta Carmi, Venezuela, El Basurero, Maracaibo, 1969. © Lisetta Carmi. Courtesy Martini & Ronchetti

Among other places, we are invited to counter events, we get to take part into this or that counter culture, like at the Convegno di Ivrea (or New Theatre Convention, in Torino, 1967), or at the Congress of the International Psychoanalytical Society dedicated to the new developments within psychoanalysis, with among others Jacques Lacan (Rome, 1969), or in Amsterdam meeting Provo’s Bernhard de Vries. We get to Israel, Latin America, India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nepal.

But my favorite, overall, it is the most frontal and sincere, probably most scientific of all the series. In the last room, the birth scenes—realized in 1968 at the hospital Galliera, in Genova—allow us to witness the most natural of the deliveries, almost removing the pain of it. The perspective discards any religiousness and poetry, and the beauty and simplicity of the composition liberate us from any sort of mystification of motherhood. As if it’d want to tell us, look this is how you came into this world, once upon a time.

Indeed, timelessness is the main gift Lisetta Carmi has left behind with her photography, both in terms of subject matters and in celebrating any instant of this suspended existence. A photography that goes beyond any documentary purpose, but rather remains as an account of the beauty and significance of minor histories.