Comrade Artist, We Have a Problem

On representation, political endorsement and dissent, freedom of speech and fascism

The following essay is an excerpt from the book Who Makes the Fash, forthcoming for ZeroBooks in Winter 2020.

In a famous passage from The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin proposed that the spectacularization of politics brings about fascism. Benjamin was referring to the growing momentum that figures like Hitler and Mussolini had gained from a manufactured charisma but with a simple glance at the West today, one would easily find a confirmation of this. Moderate attitudes and thorough analysis are not the most popular today, and consensus seems to go in the direction of the one who makes the best use of rhetorical artifacts—the loudest the better—regardless of any factual considerations.

But this is not entirely new. Already during the French Revolution, performativity started gaining an ever-growing weight in politics, as its convergence with theatre started to become more and more evident. As mentioned by Paul Friedland in the book Political Actors, after 1789 some of the most influential public figures and members of the legislative assembly either received private acting lessons, or were dramatic actors themselves, and the decisions of the assembly were more and more influenced by acts closer to theatre than political reasoning, with paid groups of “claqueurs” in the audience inciting for or against legislative measures. Both politics and theatre greatly changed in those years: actors and politicians started representing abstract roles, and the parliament went from being the embodiment of the nation to a body that spoke on its behalf. It is perhaps in the bourgeois parliament, as the place for the resolution of political disputes, that the representation of dissent began to substitute dissent itself.

With the growing spectacularization, the emphasis grew on the acts of the performers at the assembly, rather than on the actions of the citizens,* and this professionalization of the politicians brought about the figure of the spectator (both of theatre and, most relevantly in this case, of politics), relegating it to the role of uninfluential observer. And, judging by the exponential increase in the number of newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, satirical publications and political commentators, the media of the time greatly embraced the new spectacle. The ultimate degeneration of this process is the puppet theatre we witness today, in which the characters are superficially depicted as members of a “caste”, divided in supervillains, heroes, dumbasses, clowns and so on, which makes them so easy to love or hate that any real political discussion gets flattened in violent and brief flames. The characters, on their part, make all possible efforts to be as accommodating as possible, appealing to authenticity while hiding the nothingness of their stature behind carefully-crafted avatars who thrive thanks to their claqueurs, in this case hords of Twitter bots. Welcome to the representation of the representation of politics.

*Citizens which, by burning down this or that palace every once in a while – bless the Faubourg Saint-Antoine! – reminded the various political factions of the reason why they were there in the first place, and that their heads were less firmly attached to their necks than they liked to think.

“Sono Tornato”

A parallel development can be said to have taken place in the case of mass political gatherings throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. In the capitalist industrial economy, the main strategy in labour struggles was the strike, a confrontational practice in which the workers, sometimes joined by their families, abandon their workplaces, thus stopping the process of accumulation of surplus value. After the decline of the industrial economy, at least in the economies most advanced in the transition to a post-industrial model, the strike has been replaced by the demonstration, a representation of conflict which used to be linked to the strike but nowadays takes place on its own and has become the main strategy in labour and identity politics.

The term demonstration itself indicates the act of showing something, the evocation of strength that the working classes can exert, but is always an exception, usually very limited in time and space. In an anticlimactic progression, we arrive to the ultimate, edulcorated stage of the aestheticized political action: the flash mob. These kind of acts, either organized to be such, or so labelled by the media in order to dismiss the genuine political will of the participants, constitute the least radical and more liberal expression of participation, too far from political action—like a strike or a blockade—and too close to an aesthetical gesture—as a like on Facebook—to really worry the establishment, which sometimes even encourage and participates as a proof of goodwill in addressing the issues raised.

Girotondo, 2002

But let’s make our way into art. In his book In the flow, Boris Groys describes how the very concept of “art” itself, as a thing separated from life and supposed to be contemplated, also came about in the days of the French Revolution. Groys explains that the revolutionaries decided to expose the wealth they found when they stormed the palaces of the Parisian aristocracy and instead of destroying it, organized exhibitions of their luxurious belongings for the people to see.

This act brought about an aestheticization of the past regime, and aestheticization, Groys argues, is a much more radical form of death than iconoclasm. In any case it is clear that art, as a field, is heavily loaded with a transformative potential since its very birth. In a moment when the spectacularization of politics seems to have reached its peak and neo-fascism has been able to reinvent itself, from a group of stragisti and coup-plotters, fascinated with death and purity of race, to a highly trendy phenomenon, does art still have the revolutionary potential Groys describes? Can a contemporary artistic practice have a role in shaping a different hegemony?

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Fortunato Depero being total hipsters

MYTHBUSTING: THE ARTS AS A BASTION OF PROGRESSIVENESS

As with the tale of the defeat of fascism at the end of WWII, there is another tale that needs to be debunked: the one that sees the arts as an inherently progressive environment. Perhaps since the crusade of the Nazi party against the “degenerate art” that led to the shutting down of the Bauhaus, and on the wave of politically committed art that emerged in the Western Bloc around 1968 (which is commonly referred to as cultural marxism* by the right), speaking of the world of arts and culture as a hideout for reds seemed to be at the same time a rallying factor for the right, both in out out of power, and a reassuring tale for the left.

*Nothing new if one thinks of the repeated claims, by Berlusconi and his acolytes, that “the communists have ruled Italy for 50 years” and of the need to be done with the “culture of ‘68”.

The links between fascism and neoliberalism are not only present in their economic and social policies, but also when it comes to aesthetics and the arts. If we acknowledge that a large part of the neoliberal infrastructure today is fascist (think about the implementation of concentration camps and deportations for the exploitation of surplus populations for example, or of the technology developed in the context of neoliberal business models, which contributes to and stimulates practices of mass surveillance and atomization in labour and life), and that the apparatuses involved in the generation and circulation of the aesthetics and the discourses that we call art are necessarily part of this infrastructure, we have to address how these apparatuses and the discourses they produce contribute to the reproduction and articulation of the current hegemony and its steady trajectory towards the extreme right.

There seems to be, in a large part of the contemporary art world, a certain kind of disregard, like a feeling of distrust, towards both didacticism and political activism. An art that shows too much ethical commitment is easily met with the critique of being ideologically charged, and read as propaganda. The hype of “political art” since the beginning of the 2008 financial crisis, which has seen a significant, genuine participation of artists and cultural workers to protest movements, (re)sparked the interest of art institutions and galleries in politics but didn’t seem to cause any major shift in the latests’ approach to their own politics, let alone actual politics.

(source: https://observer.com/2013/07/thomas-hirschhorns-gramsci-monument-opens-at-forest-houses-in-the-bronx/)

This attitude comes in part from the training provided in art schools, where a hypercritical, detached and “neutral” standpoint is often encouraged, following the logic that once the tools of analysis and the vocabulary is assimilated, the artists can choose what degree of political radicality apply to their work. A standpoint which nonetheless does not aim at challenging the current economic system (if anything, it is a tool towards pursuing a place in the most remunerative side of the “knowledge-based-economy”), but rather focuses on the aesthetical and conceptual aspects of art practice necessary to achieve the professionalization of the field largely pushed by neoliberal reforms like the ones that followed the Bologna process. The result is an education that does not form critical minds in the arts (as in all other disciplines), but armies of skilled professionals in competition with each other, developing an artistic process usually unable to go beyond the limits of the sophisticated, white, well-mannered, self-referential, boogie-art crowds of the Western capitals. And that is dedicated to the reproduction of such social classes.

But mostly, it is an attitude deeply integrated in and sponsored by the infrastructure that produces and sells art. As art students and young artists soon learn, an outspoken attitude towards opening up new spaces for speculation that really challenge the present state of being might boil down the enthusiasm of collectors and gallery owners, as it leaves—at least since ideology and propaganda became bad words—very little space for mystification, and for profit. Even more so in the scenario described by Hito Steyerl in her book Duty Free Art, in which the fluctuations of the art market are determined by shady trading practices allowed by freeport art storages,* extra juridical grey areas to be found mostly near airports, in which artworks are stored, permanently “in transit,” out of public scrutiny. Locked in a “secret museum of the internet era, […] a museum of the dark net, where movement is obscured and data-space is clouded,” art loses even its faint social function as a device supposedly able to touch, move and fulfill the souls and minds of museum visitors exposed by its life-changing power, and becomes just another object of financial speculation. Like weapons, drugs, livestock or CO2 stored in green bonds, works of art are left at the disposal of big investors that operate in an economic and juridical loophole symptomatic of the decline of the nation state.

*“Freeport art storage is to this “stack” as the national museum traditionally was to the nation. It sits in between countries in pockets of superimposing sovereignties where national jurisdiction has either voluntarily retreated or been demolished. If biennials, art fairs, 3-D renderings of gentrified real estate, starchitect museums decorating various regimes, etc., are the corporate surfaces of these areas, the secret museums are their dark web, their Silk Road into which things disappear, as into an abyss of withdrawal”. Ibid.

These secretive warehouses are not the only art-related scenarios where the effects of neoliberalism are evident, and it would be naive to think that the top of the pyramid does not influence its lower passages, down to the smallest bricks. As in a trickle-down effect, national museums and large galleries end up partnering with dubious regimes and being part of very remunerative speculations, in a global economy dominated by neoliberal financial mechanisms that pushes for a diversification of resources leading necessarily to obscure territories. And these institutions influence, in turn, their smaller counterparts, which can do little, albeit the alleged good intentions of some of them, to challenge the very system that at best keeps them stay afloat, and at worst turns them into part of the rank and file of fascist groups.

“In the last decade, contemporary art enthusiastically put itself on the fireline between the tech world and the common folk, with the ambition to illustrate the latter what does it mean and how it will look like to live in a world with an increasingly blurry subjecthood, in between human and machine, where politics is not a necessary element of life anymore—and sweeten the pill.”

The emphasis on optimization of resources, profit making and the detachment of the works of art from their politics (hence from the environment they would potentially transform), are fertile grounds for topics easily exploited by right-wing discourses, and even an excuse to give this discourses a platform. The ever-growing need of novelty in the spectacle-craving neoliberal economy leads, for example, to an excessive focus on technology which, as Marina Vishmidt puts it, “has always been the greatest legitimation, and naturalization, paradoxically, of the desperation of the commodity to remain ever-new, ever-same. It’s no different for curatorial and institutional agendas functioning in that very same economy, driven by those same subjectivities it generates” (Vishmidt, M. [Forthcoming] Anti-fascist Art Theory: On The Potential Of Critique. Third Text. Roundtable with Dimitrakaki, A. and Gogarty, L.A.). In the last decade, contemporary art enthusiastically put itself on the fireline between the tech world and the common folk, with the ambition to illustrate the latter what does it mean and how it will look like to live in a world with an increasingly blurry subjecthood, in between human and machine, where politics is not a necessary element of life anymore—and sweeten the pill.

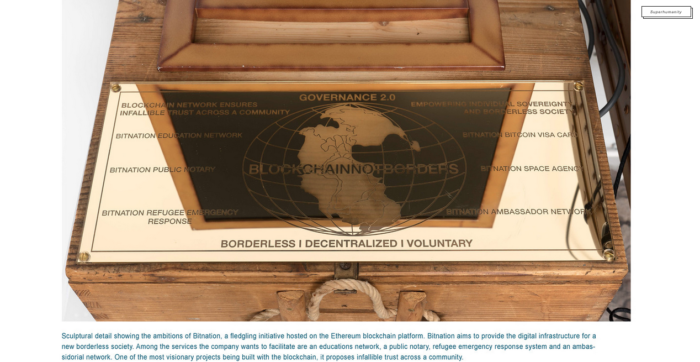

Distributed Gallery Chaos Machine (detail), 2018. Exhibition view at Schinkel Pavilion. Courtesy Distributed Gallery. Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul

To name an example, one of the most trendy topics at the intersection of technology and art is the blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies. Much like the futurists, who believed that industrial machines were going to forge a new humanity and had so much in common with the totalitarian dream of fascism, a large part of this bitcrowd seems to have an unshakable faith in the liberating power of technology, by itself capable to restructure society, deterministically reshaping humanity as a network composed of billions of interdependent nodes, in which any bit of information would be common knowledge, shared and validated by the net itself.

As in an accelerationist dream, the new prophets of the intangible foresee, for example, the undermining of the banking system via the issuing of many cryptocurrencies with no central authority. This, they claim, will bring about a truly democratic way of exchanging resources and information worldwide at the speed of light. As a result, the nation state and its borders will dissolve, as the network takes charge of its primary functions—validating the identity of its citizens and ensuring a trustworthy environment for economic transactions—thus creating a perfect neoliberal scenario, in which we free ourselves from the oppressive, bureaucratic state, without touching any of the structural aspects of capitalism.

“In a time in which the left wing seems to lack an idea of what its future needs to be (culturally even more than politically), this rhetoric appeals to the need for novelty, but with a logic of management of resources and decision making typical of a business oriented mindset and supposedly unavoidable: ‘the only way out is the way through.’”

The artists that partake in this fascination like to cloth themselves with an aura of underground and avant-garde, copy-pasting left-wing keywords like horizontality, borderlessness, participation, direct democracy, and mixing them with less politically connotated ones like decentralization and transparency. In a time in which the left wing seems to lack an idea of what its future needs to be (culturally even more than politically), this rhetoric appeals to the need for novelty, but with a logic of management of resources and decision making typical of a business oriented mindset and supposedly unavoidable: “the only way out is the way through”.

The problem with these practices that reproduce an anarcho-capitalist vision in which improving the channels of distribution ensures enough efficiency to overcome politics and sustain a stateless society, is that their foggy aesthetics hide the fact that the neutrality of technology is a dangerous myth, and that such technologies can only serve any good purpose within a historical, political and social reading of their potential. If politics is removed, if the myth of neutrality is implemented, if the substantial economic and hegemonic conditions stay the same, then those tools can only strengthen the dominant ideology, leading to a “liberation” that includes only the white subjects who have the possibility, and the will, to participate and normalize, from a position of power, this technocratic, god-like entity of atomized, self-possessing nodes à la Matrix. The other billions, what Marx called surplus population, living in the rural areas, in the slums, stuck in poverty and slavery, sieged by climate changes enhanced by millions of servers processing 24/7 will only face another, insurmountable segregation wall.

Screenshot source e-flux: Block Chain Future States

The act of promoting a novel, apparently apolitical art is thus not as harmless as it seems at first sight. As Larne Abse Gogarty shows in her article The Art Right, the alt-right is very aware of the potential of an ambiguous aesthetics and it exploits post-internet tropes to recruit confused liberal souls. In her piece, in which she discusses the scandal around the London gallery LD50, an example of a gallery that went all in in their support of openly fascist art, she quotes a Google document, found on the political section of 4chan, titled Westhetica, …the anonymous author suggests “synthesizing” … futuristic themes with a classical greco-roman base … 80s retro neon vibrancy … postmodernism and distinct irony alongside new-age imagery. These are all classic vaporwave and post-internet associated tropes, and the document further stresses the idea that “emphasis on aesthetics helps separate the notion of white identity from fat spergs/skin heads and dorky cuckservative stiffs in order to gain wider appeal.” The aim is to “appeal to the more Bohemian type of people … They could be drawn in by the aesthetics and then get redpilled with incremental exposure to the ideas of the alt-right.” This stands as an attempt to rebrand the culture typically associated with white supremacist movements in order to assist in the goal of entryism among the young, white bourgeoisie.

As Gogarty acknowledges herself, the case of LD50 and of that particular event is an extreme one: the gallery, located in one of the most important targets of gentrification in the UK, organized in 2016 a series of very secretive conferences on neoreactionary thought featuring right-wing speakers like “Iben Thranholm, Peter Brimelow, Brett Stevens, Mark Citadel and, finally, Nick Land” which relied heavily, for its organization, on the network of American neonazi websites such as Amerika.org. In what seems like a direct result of this plotting sessions, a later show displaying alt-right aesthetics, tweets by Trump and a number of other alt-right influencers, neonazi internet imagery was organized, with the clear intent to glorify the milieu in which neoconservative and alt-right discourse is fabricated and legitimized by the use of the contemporary art’s “aura”. However, as the discussion above suggests, promoting alt-right artists does not necessarily have to be part of the agenda.

Source: https://shutdownld50.tumblr.com/

Aware or not, deliberately or not, the resources the art world has to offer, like financial support, spaces and a certain credibility when it comes to the elaboration of discourse, can very easily go to the right. The issues (along with certain figures involved in) the LD50 controversy, for example, came back to the spotlight in the case of the 6th Athens Biennale, titled ANTI, a similar case of an art institution that, to say the least, refused to censor fascist behavior within its own “circle”. The Biennale proposed itself as “an agonistic space hosting different approaches on how to deal with ominous tendencies in politics and culture”. However, when confronted by artist Luke Turner, one of the invited exhibitors, about the participation of Daniel Keller in the Biennale, an artist with an ambiguous approach towards antifascism, who recently defended the abusive behavior online and life-threats by two other artists against Turner himself, the curators of the Biennale, while remarking their antifascist artists’ CV, washed their hands and pulled the good old “we need to encourage discussion, and if you want to censor another point of view, you’re not welcome” argument. Comrade artist, we have a problem.

THE SELFIE IS MIGHTIER THAN THE ARTWORK

One final note on being a politically committed artist. If both the ideas that art has a transformative potential and that it can’t be a substitute for politics are true, then politics, art and life can’t be separated. Being an artist does not exclude one from also being a political subject in a society, whatever one’s status. It might seem an obvious statement but it can be complex to navigate while dealing with issues of cultural production.

credit: twitter @barone_rotto

There is in the present moment, obviously, a right wing that resorts to strategies that we are used to associate with the left for the creation of common sense. The new right embraces cultural representation with the goal of getting rid of cultural marxism by confusing meanings and struggles in order to legitimize its own agenda: for example, the claim by the most extreme right-wing movements of protecting the right to freedom of expression is traditionally a claim of the left. So deep is the reach of the intellectual short-circuit around this issue, that people who oppose fascist gatherings and contest right-wing politicians in their public appearances are accused by liberals and the mainstream media of “directing public attention” to them. This while broadcasting the same racist groups and individuals and allowing them to perform their own self-victimization, which means that they cannot be criticized publicly without an accusation of an assault on freedom of expression. Basically, a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A freedom of expression which means, it goes without saying, that they can disseminate all their racist, homophobic and misogynistic rants without consequences. This trap of freedom of expression, intended as a sort of unquestionable licence to kill like in a James Bond movie, is such a strong, toxic narrative that it has permeated the liberal left to such extent that the institutional left wing rushes to express solidarity with the right whenever they are opposed at public events. Even personalities of the cultural world of whom a deeper level of analysis would be expected inexorably fall for it. A recent example involved one of the most praised political artists of this decade, Ai Weiwei, who recently defended the choice of taking a selfie with AfD politician Alice Weidel with the following words: “I don’t believe that differences in political views or values between people should act as a barrier in communication, […] My efforts are in tearing down those boundaries. Alice Weidel is a democratically elected politician and has the right to freely express her political views. Although her views are completely the opposite of mine, no one has the right to judge her personal life. […] If you cannot tolerate free expression, your political views are even more terrifying.”

So much for the political artist. Mr. Weiwei—along with whoever aspires to have a publicly recognized voice in political matters, that is, matters that embrace a collective scope—should, in my opinion, consider the weight that his words have, which is no less than, if not more, than that of his art. If Weiwei can’t tolerate criticism for taking a selfie with the member of a party of white suprematist, racist holocaust deniers—which reads as political endorsement—then he should have chosen a different career, or stuck to less problematic and equally remunerative gallery art. As they say, if you can’t stand the heat, leave the kitchen. You don’t want to run the risk of finding yourself cooking in the kitchen of CasaWeiWei.