Complaining of Supermarket Tomatoes

Canedicoda works in his nomad studio-atelier and opens its doors only by appointment

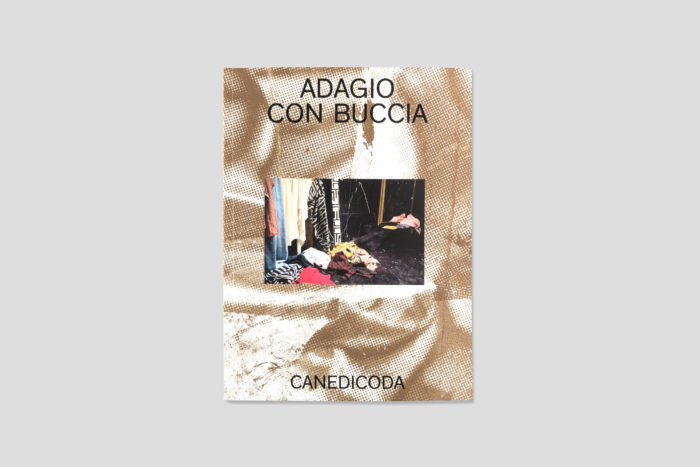

The following essay is from Adagio con buccia (NERO Editions, 2018), a book by Canedicoda, telling the story of a project that unfolds from an intuition on the performative potential residing in the act of making an object, in particular tailoring clothing on mindful bodies. On Saturday 20 October 2018, the book will be launched by Xing at Raum, in Bologna

AROUND

I first started Adagio con buccia in my studio out of necessity and curiosity; and it essentially refers to my study of how clothes are created and used. During the April 2015 edition of Live Arts Week, through discussions with Daniele Gasparinetti and Silvia Fanti, I’d say that Adagio con buccia found a sort of “official” channel and context outside my own private sphere. On that occasion, without really even noticing it too much, I met with 27 people in 4 days. The event was billed as an ad personam performance. The idea was to create, in approximately one to one and a half hours, a wearable—or at least usable—object. That meant six or seven appointments a day in a rather protected environment, one-on-one, face-to-face, with people I knew and people I didn’t. There was the meeting, a brief explanation of what was going to take place, a sort of introduction to the project, then little by little our reciprocal engagement in the creation of the possible garment. There was my desire to open up, to unveil a process and share a technique. My greatest expectation was to generate something useful for the person that somehow broadly portrayed some of the physical and personality features of my guest. There was also my curiosity about the guests: how much would they participate, to what extent would we be able to help each other and how. Being alone with a person you don’t know, for a very limited span of time and with a specific purpose. It was always a big challenge.

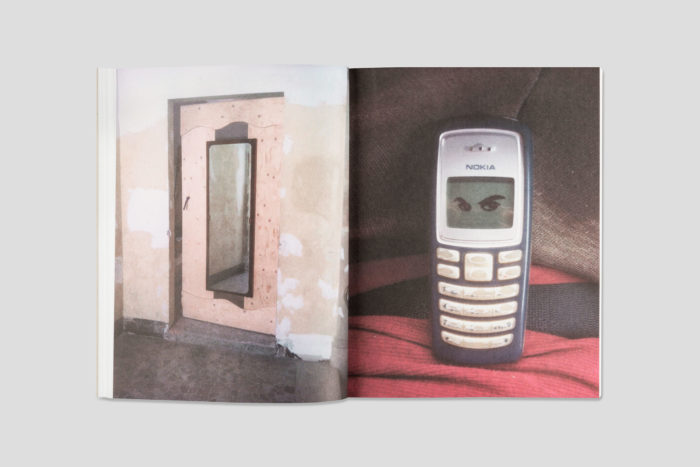

Adagio con buccia, Canedicoda (NERO, 2018)

Luigi Bonotto is the founder of Bonotto S.p.A., with its main office in Molvena, Vicenza. Bonotto is an important textiles company that I’d been in love with for some time. The first time I submitted this project to them, very cautiously seeking out their help, my ideas weren’t all that clear because everything was still in a rather embryonic stage; but I trusted my intentions. I felt a sparkle of joy and an interesting shiver while I instinctively chose and selected bolts of fabric once I’d gotten permission. A great gift. At the end of the first round of 27 appointments in Bologna, I felt it was necessary to extend the measure of comparison to a generally larger number of people and, to the extent possible, to different geographical areas. Simply put, clothing must meet our needs in terms of climate and our social role and it must actually be comfortable and esthetically pleasing. The next stops of Adagio con buccia were to be elsewhere, according to the limits and possibilities of the situation, but elsewhere. Aim for 100 appointments.

From there to Milan: a city that has always reflected on clothing, with all that fashion scattered around everywhere. Whether it’s the staff or the higher ups, there are lots of people in the city who really need their clothes to quickly communicate to others who they are. It’s easy for an outside observer to see just how much Milan wants to feel beautiful and elegant. So yes, I just had to schedule a stop in this city that’s been hosting me for some time now. Then luck stepped in and the opportunity arose. An important jump, into a luxuriously ancient environment. Plants and marble palaces, water, carpets, and mirrors. And those were intense hours too; 32 underground appointments in 6 days: my desire to see outside began to surface. And then one summer I came across this little town on the lake: one of those perfect little spots. Great, lots of coincidences: I came upon traditional needs and a taste that was partially freer and more personal—let yourself get carried away by curiosity. Another 32 events in exactly 6 days in Switzerland. I ended that series in my studio with the calm or slowness you feel when maybe you just don’t want it all to end, or you’re trying to savor your last bites in a different way. I found nourishment in these appointments that made me reflect on how to carry on making clothing like this. Who is the person I’m meeting, if not indeed the one who’s going to be using the object? Various transitions were skipped over and, theoretically, there were only two people who were getting in touch. Paradoxically, this was supposed to be a luxury. In pursuit of greater efficiency, trying to fit in more and more.

Adagio con buccia, Canedicoda (NERO, 2018)

INSIDE

I’m interested in clothing. I’m interested in creating objects that are practical, that you can touch, that wear out with us, following our movement. And that accompany us: our protection and our story, for ourselves and for others. To tell you the truth, I’m not crazy about fashion at all, or how fashion often seeks to be perceived. Although I’m happy to deal with bodies and fabrics, I’ve never really wanted to have a traditional fashion show, but more than anything, I would never want my name, Canedicoda, to become a brand. Why? Maybe simply because I want to be free, or maybe because of a healthy immaturity. I want responsibilities that fit with my awareness. I believe in time, in a time that is long but doesn’t make us forget. Or is it better to lightly vanish away? Leave it behind.

What coexists in the world, willingly and without causing mutual harm. It’s not like this project is something new—making clothes by appointment while you’re talking and getting to know each other, where the relationship is guaranteed and the space is as real as possible—however, it’s probably reasonable to think that we still don’t need another designer, another sales campaign, other prototypes, more and more other products. Or at least—and perhaps much easier—that I’m not actually a designer within the context of fashion. Still very careful about money, whether it’s a lot or a little, it’s never enough. Never entirely carefree and never fed up.

It’s funny to see rich people who are unhappy or who’ve just dropped dead on the toilet. It won’t even be that long, I’d say. Direct and prosaic. Vulgar but healthy and in the bag. A jump into the bag. That’s it, more than anything I’d like to be healthy, have real ideas; and get rid of as much trouble as possible. Adagio con buccia arose from a need for relationship, to feel transparency with my own hands. Perhaps even unveil some arcane mystery, at least to myself. Debunk the myth that only I can do it. Offer an experiential lunch, share a two-headed yet potentially convergent gaze.

Far Festival Nyon, Switzerland – August 2016

Reflecting on the untouchable nature of art, the unattainable nature of gesture, the objective nature of genius. I’d gladly melt when people talk about art. Perhaps it’s my superficial gaze that reaches out to dismantle people’s trust in systems of fashion and art (which might ideally be respectable conversationalists?) However, what I want is optimism that is pure and origins that are worthy. Mobile. That’s it, this has often proven to be a useful way of looking at things: their changeability. Knowing how to jump from one thought to the next and that the mind physically moves us elsewhere, moving our feet to arch our back toward other things that are constantly opening up.

In the diversity of the bodies and minds of those 100 parallel meetings, I experienced postures and people’s perceptions of themselves that were changeable. And I told myself: We really don’t realize that living in movement, we feel better when we’re moving, yet we often stand there immobile in front of the mirror, or too close, observing ourselves in a way that never does us any good, that’s probably stifling, even for beauty that’s entirely unbiased. Scrutinizing the mirror may generate false impressions. I’ll say it again: We are in constant motion. Inside and outside. Something is constantly being used up. Even in our perceptions of time.

So this work has also given me the opportunity to reflect on the issue of time: two hours per appointment, sometimes less, sometimes more. It isn’t too little time; it might be enough if we manage to stay focused. And at first having a timeframe seemed like a pleasure. On many occasions, however, the clock turned into a wretched companion, an unpleasant presence; ready to remind me of my duty to be efficient and the possibility of surrender. Right when I told myself I had a penchant for error. The longing to fail was great at times, to discover and share the absence of desire: That train’s just left, sorry sir, we just can’t get that stain out. It’s all sold out, without even really talking much about merit.

Or saying, come on, we can do it, either to myself as if it were a personal goal or an experience that is largely cooperative: a chance to come up with a solution in the here and now. It’s true, it’s just an object—maybe even something simple, like a dress—but on the other hand, there’s a very fragile world there, made up of arms, shoulders, legs long and short, necks stretching upward, heads that tilt to the right or left or that look up. And our entire way of moving, breathing. A being enveloped inside a body. Perhaps our essence is just protected by that body. It might be, right? I write innocently, free. It’s good to know how to accept yourself, even like yourself. I don’t mean pride; pride seems ridiculous to me, and often risky. All it takes is a bit of it to dismantle your courage. A little water or a little cold air is all it takes. The elements that came before us and that will undoubtedly go on without us are all it takes. How far thoughts reach, or how much they inundate people’s minds.

Far Festival Nyon, Switzerland – August 2016

Still on Adagio: 100 people is a generic number used to express an actual amount. “I’m going 100 miles an hour,” someone once sang. Vanna’s fans screamed “100!” while running the 100 meter race, or 100 as a number to express a commitment. I remember something about every appointment. I tried not to repeat myself, to listen to every voice, just trying to go with it as much as possible and hoping to be amazed. And, excuse me, but what is this amazement? How many times can we play the same game without getting bored? I’d try to find a method for simplicity. There’s a beat, a rhythm, a way of observing that registers and strives toward awareness. I perceive myself in a body, a context, and I formulate experiences. Hands are offered. Lead and be led. Relationships with a double transition: an internal and external one. I sought dialogue with each person, considering each person unique. It was a mirror that definitely wasn’t monotonous. Some garments turned out better, in a unique flow, and so I’m sure that in the hands of the “co-pilot” it will perform its function of being a good, useful object. Others turned out less loaded, less emphatic, or just wearier, for many reasons, like dog and cat or even because of the specific case or point of view.

I’ll gladly accept what took place. I also learned that there are fabrics that are easier to work with and others less. Fabrics that are easy to control and others whose fragile rigidity commands respect. I also found out that I don’t want to force anybody (materials included) to be anything except for the pursuit of themselves. For the next freeze: a tissue paper raincoat. For the next hot spell: a knit shirt made of itchy wool. Everything in its place, without wasting, please. Without producing garments before finding someone to purchase them, and without desaturated purchasers in comfortable uniforms.

These are common questions but it’s always fruitful to learn from experience. I’m sort of addicted to clothing that I create for my own use. Kind of like the winemaker that produces a healthy wine and doesn’t enjoy drinking industrially produced wine. Kind of like a grandmother who tends her own garden and complains of supermarket tomatoes that don’t have any flavor. Ideas and awareness are generated. Perhaps temporarily and there are a thousand questions that may or may not contradict each other. Caught in a neverending paradox, I’d like to conclude my reflections on this project with a salute to all the clothes we’ve loved and love, to all the caring moments.