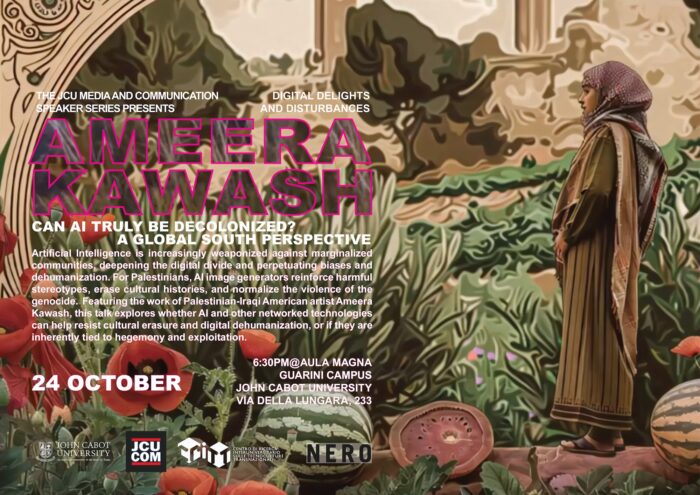

Can AI Truly Be Decolonized?

A Global South perspective

Artificial Intelligence is increasingly being weaponized against marginalized and oppressed communities, deepening the digital divide while perpetuating biases and digital dehumanization. In the case of Palestinians, popular image generators often reinforce harmful stereotypes, erase cultural histories, and normalize the violence of genocide. Featuring the work of Palestinian-Iraqi American artist Ameera Kawash, this talk asks: what if AI technologies were employed to affirm Palestinian narratives and futures rather than contributing to their erasure, epistemicide, and digital dehumanization?

In this talk, happening on October 24th at 6:30PM at John Cabot University’s Aula Magna (via della Lungara 233, Roma), Kawash will elaborate on her participatory, critical archival methodology aimed at reimagining generative AI systems. By resisting the “futuricide” of the Palestinian people, her project seeks to transform AI into a tool for amplifying and safeguarding the stories and futures of marginalized communities rather than aiding their erasure.

Digital Delights & Disturbances (DDD) offers radical ways to think out-of-the-(digital)-box we live in, imaginative and informed food for thought to feed our souls lost in the digital mayhem. DDD is organized and sponsored by the Department of Communication and Media Studies at John Cabot University, in collaboration with NERO and CRITT (Centro Culture Transnazionali).

Make sure to RSVP via this link, or follow the Livestream here. More info at [email protected]

How does AI normalize violence?

Ameera Kawash: The question of whether AI normalizes violence is critical when considering if AI systems can be demilitarized and the role consumer technologies play in normalizing the nefarious uses of AI.

We are already seeing AI integrate into military systems, most notably Israel’s use of these systems in coordination with lethal drones and strikes, mass targeting individuals and communities in Gaza, amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

High-speed computing, machine learning, and automated decision-making are rapidly becoming part of military technologies. Furthermore, digital dehumanization is closely connected to datafication. Digital dehumanization, as defined by Automated Decision Research—an advocacy group monitoring autonomous weapon systems—is the “process whereby humans are reduced to data, which is then used to make decisions and/or take actions that negatively affect their lives.”

As AI relies on the datafication of human and nonhuman life, reducing complex and rich systems to data points, we must be highly critical of the potential violences and the seemingly smooth functioning of technological processes that are reductive, generalizing, and potentially annihilating.

This is true for both highly dangerous AI as well as popular Generative AI models, which also contribute to digital dehumanisation through biases, omissions, or in the way that violence, war, or genocide is depicted synthetically in Gen AI media.

At the same time as doing our best to counter all forms of digital dehumanisation, we should expand our understanding of data to include human-rights-centered and ecosystem-centered approaches to datafication, radically altering data ontologies to center empathy and life-affirming principles.

What is the subversive potential of AI?

The subversive potential of AI is tied to calculating or weighing the risks of either not participating in the system or only engaging passively—or worse, being forced into a non-consensual system. This is already the case with AI being used in case management in welfare systems, immigration, weapons, or surveillance technologies.

There is a danger of further weaponizing the digital divide, impacting economic development, health, and creating more unhealthy dependencies and asymmetries between the Global North and South. The consequences of exclusion from these systems can further entrench the digital divide or create situations of technological apartheid, where one group has access to high-speed computing, servers, and AI while others do not.

AI cannot simply be “put back in the box,” and not having minoritarian, Global South, and marginalized perspectives in AI innovation is deeply worrying and a significant global loss. We should, however, use these systems while demanding the demilitarization of AI and global accountability.

How can AI contribute to the preservation and application of stories and futures of communities at risk of erasure?

First, AI contributes to epistemicides at scale. This manifests through manifold biases, such as anti-Muslim bias, where violence is disproportionately associated with Muslims over other groups. As knowledge and culture become increasingly datafied, there are inherent violences in this reductionism. Moreover, there is a danger of further erasing the knowledge of oppressed, at-risk, and indigenous peoples, as well as ephemeral forms of knowing and being.

However, we are seeing initiatives around indigenous AI, for example, that combine traditional knowledge with AI. Artists are using AI to address archival violence caused by colonialism. It is fascinating that generative AI is structured like an archive—with vast amounts of data indexed, categorized, processed, and retrieved; yet, unlike traditional archives that focus on preservation, generative AI is future-oriented, creating an archive of possibilities.

In your work, you often bring together traditional and ritualistic practices and AI (as in Tatreez Garden and Black Body Radiation). How do they coexist in the same framework? What are the challenges and potentialities of overlapping them?

In Tatreez Garden, I trained AI models on Palestinian embroidery and plants from the Palestinian ecosystem that are vital to diet, culture, and tradition. I was surprised by how well the AI learned to embroider!

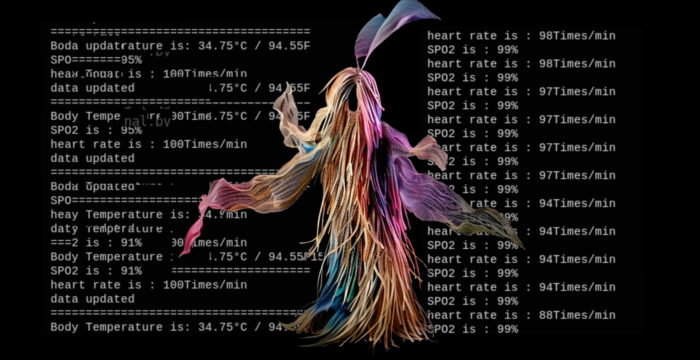

Black Body Radiation, a collaboration with artist Ama BE, references West African masquerade traditions and rituals. The goal was to use AI and the technological backend to create alternative methods for documenting performance artworks, which are a form of ephemeral knowledge. Instead of photos and videos, the documentation was tied directly to the performer’s body metrics. The idea was to make the process artist-led and intimately connected to Ama BE’s gestures and bodily movements.

In these cases, I approach AI as a critical archival practice, leaning toward iteration and future possibilities. I don’t believe there is an inherent conflict between tradition and technology, drawing from Afrofuturism, I reject this binary. Perhaps we need to expand our definition of technology to recognize ritual and other forms of knowledge as part of technology and science. Part of undoing the violence imposed by technology involves expanding our understanding of what technology means.

How have you engaged with ethical automation? And how can AI be diverted toward the affirmation of Palestinian futures instead of their annihilation?

I am actively trying to engage with ethical automation in projects like Tatreez Garden, which I am developing into a fundraising and advocacy tool to support Palestinian organizations and causes. Generally speaking, ethical automation should center consent, social and environmental impact, and a human-rights-centered approach to technology. Ultimately, it’s about whether we can build systems of digital humanity and digital resilience that can better support all life on the planet.

With regards to Palestine and Palestinians, especially in Gaza and the West Bank, high-tech technologies have generally been used as tools of violence, to impose injustice and inequality, and “scholasticide,” “culturcide,” and “futurcide” on Palestinian society. Israeli society is often depicted as high-tech and future-oriented, while Palestinians are forced into deliberate de-development, restricted, oppressed, and erased by these technologies.

This weaponization of the digital divide, created by Israel by limiting Palestinian economic growth, control over cell phone frequencies, infrastructure, and hardware imports, should serve as a warning to all of humanity as to the dangers posed by extreme information, digital, and technological asymmetries.

Gaza is limited to 2G internet and suffers from massive blackouts while enduring the horrors of Israel’s unfolding genocidal war. Yet, despite these immense challenges, brave citizen journalists in Gaza continue to share their stories with global audiences. I agree with Mariam Barghouti that the future of journalism is being upheld by the integrity of Palestinian journalists, even as this genocidal war has been deadly for journalists.

In using AI to support Palestinian life, culture, and futures, one goal is to counter the incredible violence that results from the weaponization of the digital divide. Additionally, if AI is used to support Palestinian life and futures—whether through archives and digital humanities, documenting and protecting human rights abuses, or improving health services—it will have a positive impact on the rest of the world. If we center Palestinian life, as well as the lives of marginalized and oppressed groups, in these systems, we stand a better chance of making AI serve digital humanism and not rampant militarization and the weaponization of the digital divide. In doing so, we support life on this planet for everyone.