The Calm Before the Storm

Chronicles of the psycho-deflation #4

April 4th

Lucia found a black and white photo and sent it on my phone. In the photo a young, beautiful woman is wearing her Sunday best, as girls used to in the 30s. With her, there is another girl.

In the background there’s a building I easily recognize. The woman and the girl are walking along via Ugo Bassi, at the back there is the triangular pediment of the building that separates Pratello from San Felice. The young woman is looking ahead, with a slightly absent look, while the little girl almost clings to her hand, seemingly demanding attention, but the woman does not look at her, she looks away ahead.

That woman is my mom, and the girl is her cousin Maria.

I immediately wondered who might have taken that picture, who was behind the camera. I am sure it’s Marcello, her fiancé. My grandfather Ernesto allowed Dora to go out with him on weekends, but on the condition to be accompanied by someone, be it a brother or a girl. Dora looks bothered, a little haughty, perhaps annoyed by her cousin’s unwanted presence. She does not turn toward her, she looks at him, at the photographer who captured that instant. She looks far ahead, towards the future she imagines, on that feast day of spring in the late 30s—when my mom was just over twenty years old, and any tragedy seemed distant. Then the war came and devastated, upsetting the life and the future she had long waited for.

April 6th

A grim calculus. This week’s The Economist title says it all. “Grim” means bleak, gloomy, and even fierce. A sad calculation we are forced into. It is easy to grasp what the magazine that has represented liberal economy for more than a century meant with this title. How much the coronavirus pandemic will cost us in economic terms, and what kind of considerations are cast upon us, such as having to choose between two alternative decisions, namely to close everything down and almost completely block any production, distribution—in short, the whole economy machine—or to accept the possibility of a massacre.

I read in the London magazine, “The governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, has declared that ‘We’re not going to put a dollar figure on human life.’ It was meant as a rallying-cry from a courageous man whose state is overwhelmed. Yet by brushing trade-offs aside, Mr Cuomo was in fact advocating a choice—one that does not begin to reckon with the litany of consequences among his wider community. It sounds hard-hearted but a dollar figure on life, or at least some way of thinking systematically, is precisely what leaders will need if they are to see their way through the harrowing months to come. As in that hospital ward, trade-offs are unavoidable.

Their complexity is growing as more countries are stricken by covid-19. In the week to April 1st the tally of reported cases doubled: it is now nearing 1m. America has logged well over 200,000 cases and has seen 55% more deaths than China. On March 30th President Donald Trump warned of “three weeks like we’ve never seen before”. The strain on America’s health system may not peak for some weeks (see article). The presidential task-force has predicted that the pandemic will cost at least 100,000-240,000 American lives.

Just now the effort to fight the virus seems all-consuming. […] But in a war or a pandemic leaders cannot escape the fact that every course of action will impose vast social and economic costs. To be responsible, you have to stack each against the other. […] By the summer, economies will have suffered double-digit drops in quarterly gdp. People will have endured months indoors, hurting both social cohesion and their mental health. Year-long lockdowns would cost America and the euro zone a third or so of gdp. Markets would tumble and investments be delayed. The capacity of the economy would wither as innovation stalled and skills decayed. Eventually, even if many people are dying, the cost of distancing could outweigh the benefits. That is a side to the trade-offs that nobody is yet ready to admit.”

All clear. The Economist confronts us with a way of thinking that despite its apparent brutality, it is simply realistic. Another headline in the magazine says “Hard-headed is not hard-hearted.” Who can deny it? Due to the decision to stop the flow of any social activity and the economy flow, political leaders have certainly saved millions of lives in the next three, six, twelve months. But—The Economist observes with uncompromising consistency—this will cost us a much higher number of lives in times to come. We are avoiding the massacre that the virus could cost us, but what scenarios do we prepare for the next few years, on a global scale, in terms of unemployment, production breakdown and distribution chains, in terms of debt and bankruptcies, impoverishment and despair?

Hold on a second.

The Economist editorial is reasonable, coherent, irrefutable, but only within a context of criteria and priorities which corresponds to the economic form we call capitalism. An economic form that makes the allocation of resources, the distribution of goods dependent on participation in the accumulation of capital. In other words, it makes the concrete possibility of accessing useful goods depending on the possession of abstract monetary securities.

Well, this model that has allocated enormous resources for the construction of modern society, today has turned into a logical and practical trap we could not find an exit from. But now, the way out has imposed itself automatically, unfortunately with violence. Not the violence of a political upheaval, but the violence of a virus. Not through the conscious decision of forces endowed with human will, but the insertion of a heterogeneous corpuscle—like the wasp would be to the orchid—a corpuscle that began to proliferate until the collective organism was unable to understand and want, unable to produce, unable to continue.

This has stopped the reproduction, sucked up huge sums of money that end up to be of little or no use at all. We have stopped consuming and producing, and now we are here, looking at the blue sky from the window and we wonder how all this will turn out—bad, very bad, says The Economist, to whom the interruption of the cycle of growth and accumulation appears to be a catastrophic event that will lead to starvation, misery and violence.

I allow myself to disagree with The Economist‘s catastrophic tone, because I intend the word “catastrophe” differently—as in its etymology it can also mean “a turning beyond which you can see another panorama.” Kata can be translated as “beyond” and strofein means to move, to change. So, we moved beyond, we finally made that move that fifty years of determined and loquacious conscious struggles have failed to carry out. Everything—or almost everything has stopped, now it is a question of restarting the process, but according to another principle—purpose rather than abstract accumulation, frugal equality for all rather than competition and inequality.

Will we be able to develop this principle to restart the machine—not the same machine that worked relentlessly before, but an elastic one, a machine perhaps a little more shaky, surely more frugal, but a friendly machine?

Will we be capable? I don’t know, and above all I don’t even know who would make that “we.” Who will be capable of what?

No longer politics, nor the art of governance. Politics is incapable of any governance and above all it is incapable of any understanding. The poor politicians seem to be hunted, staggering, anxious. The new game of the rhizomatic proliferation of ungovernable corpuscles calls for knowledge—not will.

Therefore, no longer politics, but knowledge. But what kind of knowledge?

Not The Economists’ knowledge, unable to get over the mirror house of valorization, which accesses any product as abstract terms of monetary calculation and increases the volume of destruction in order to increase the abstract value. I mean concrete knowledge, a knowledge that does not translate profit into value, but purpose into pleasure and wealth.

Do we need F35 fighter aircrafts? No, we don’t. Other than favoring futile military alliances, they are useless. Those workers could rather produce tuna cans. Also because, do you know how many intensive care units one could make out of a single F35? Two hundred.

I know, these are loosely-spoken tales that don’t take into account all the complex interdependencies behind them and so on. Okay, I’ll shut up. So let’s listen instead to the speech of those realists who chant the same song on repeat: if we want to keep the occupation at current levels we have to produce weapons, don’t we? Say The Economist realists, both those on the right and those on the left.

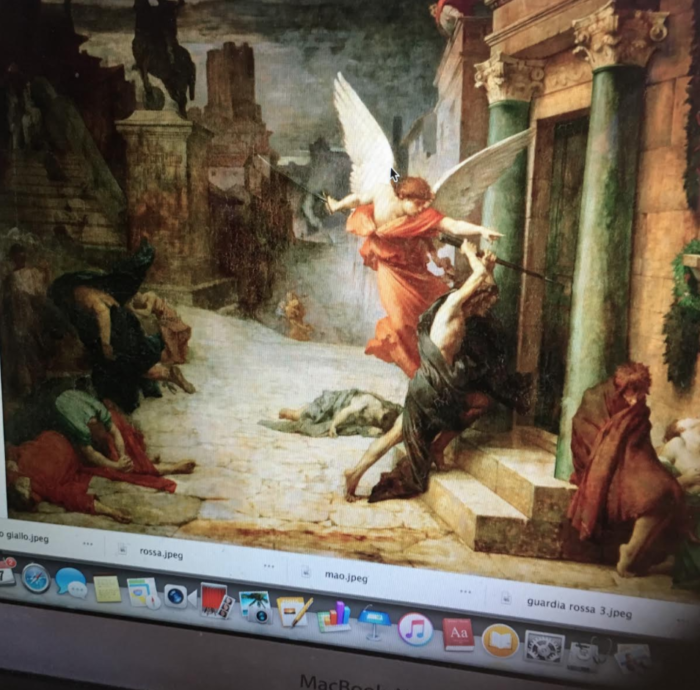

So we will continue to manufacture weapons to make all those people work eight-nine hours per day. In a month or a year from the epidemic, mass misery will follow, then war. And the extinction we just had a taste of, will come and greet us on his beautiful white horse, as in The Triumph of Death at Palazzo Abatellis, in Palermo.

What if instead we decide to make people work only for the time necessary to produce what is useful? What if we gave everyone an income regardless of their (otherwise useless) working time? What if we stop paying for the useless aircrafts they’ve already bought? What if we screw up international bonds that force us to pay huge sums of money to afford the war?

Here: these speeches are no longer the ranting of an extremist, but the only possible realism. There is no alternative 😉

My friend Penny wrote to me from London: “I just sit and write—this strange life has become familiar and calming but that is always calm before the storm.” There is always a strange silence before the storm breaks out. As if to say that the best part will come when the tired virus withdraws. At that point the fools will think it is time to return to normal, while the wise are already busy preparing for the bigger storm to come.

April 7th

After two months almost completely in hiding, asthma has returned today, and has haunted me all day. Lying in bed I gasped without oxygen and no strength to do anything.

In the evening I go to get the trash out: organic, glass, undifferentiated. I walk slowly in the little square below the house. The San Donato Best Western Hotel is closed, bolted with the shutters pulled. I walk a bit on via Zamboni to see the towers. There is no one in this street where, since the twelfth century, every spring students used to flock and court.

April 8th

I take my coffee and look out into the sunny square. Even today there is that girl who comes out from under the vault, perhaps she lives alone in a studio apartment in Via del Carro. She has a black outfit with yellow edges, she holds her phone in her hands while doing her daily exercises. Her movements are a little awkward, she raises her right leg and holds it up for a few seconds, but the cell phone draws her attention, then she raises the left leg while staring at the phone, then turns around and places her arms on the wall, and turns her head back and forth. My phone rings, I walk back inside. They call me from Milan to ask if I can still send a recording for Radio Virus today. I go back to the window, the girl is gone.

If his earthly representative didn’t forbid considering this illness a God’s punishment, I would assume that the Lord is a witty old man. He sent Johnson to intensive care first, then he sent the homophobic Israeli Minister Litzman. Litzman previously stated that Covid is a divine punishment for homosexuality.

Unfortunately, this is the only comforting news coming from that racist country. For the rest, the Israeli political chronicle tells about the endless brawl between the torturer Ganz, the corrupt Netaniahu and that Nazi, Lieberman. Probably they will go for the fourth election in a year, as the world dissolves around them they are too busy arguing to even realize.

According to the International Labour Organization in Geneva (ILO), the pandemic will cause an average 25 million increase in unemployment this year. In the States there have been over ten million layoffs in two weeks, and the number is expected to increase in the coming days. To use one of the most popular expressions of these days, these are unprecedented numbers.

Traditional economic policies will not suffice to deal with this phenomenon. Either we will resort to the violent marginalization of a huge part of a population of miserable people roaring in the city outskirts, or we should abandon once and for all the whole “modern economy” discourse, the old “full employment” utopia, the “wage labor” prejudice, and literally start all over again. What remains certain is the accumulated scientific knowledge, and above all the vital power of cognitive work, technical inventiveness as well as the poetic word.

But the economic criterion that so far regulated relations and their priorities has definitely gone mad—out of order, forever.

If we try to restore the old relationship between those who have wealth and those who have to work to earn a living, then misery will generate rivers of violence, unemployment to feed desperate armies ready for anything.

It will be a matter of requisitioning production spaces and structures. It will be a matter of regulating access to available resources under conditions of equality.

We cannot waste time in the illusion of returning to a past “normalcy” because this illusion risks dragging what remains in a spiral of devastation, with no return. What consumers expected in the past fifty years is gone, and must not come back. The system of expectations itself should radically change.

If I would have to pick an event, a date and a place as the origin of the apocalypse, I would say that that event is the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992. For the first time, the great nations met to assess the need to address the dangers that economic growth was beginning to reveal. On that occasion, the President of the United States, George Bush senior declared that “the living standard of the American people cannot be negotiated.”

Now we are all paying for his pride, which is perhaps inherent to the very existence of a nation born out of genocide, whose wealth depends on deportation, slavery, war and robbery of other people’s resources and labour. That nation will soon face a devastating internal war and, deservedly, won’t survive it.

April 9th

After a month of seclusion and uncertainty on the implications of this situation, a certain nervousness is perceived in the voice of friends who call me, but also in any written record, or analysis I get to read everyday. I do not read everything really, but I do read a lot.

In a mailing list titled Neurogreen, I got an article today written by Laurie Penny, published in the Californian magazine WIRED, which for many years has been the frontrunner of a digital futuristic and ultimately ultra-liberal imagination and vision.

It is strange to find such an article in such a usually ultra-optimistic magazine. The piece is most likely an account of a rather dramatic personal experience. Laurie Penny finds herself god-knows-where, far from home, surprised by the viral storm. “Capitalism cannot imagine a future beyond itself that isn’t utter butchery. […] Social democracy is being reinstated in a hurry, because—to paraphrase Mrs. Thatcher—there really is no alternative.”

150 members of the Saudi royal family got the virus. Bernie Sanders retires, Biden will lose the elections, (or maybe not) if elections will be held at all. Eight doctors died in Britain for treating patients with the virus. All of them were foreigners: Pakistani, Indians, from Egypt, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Sudan. Delhi’s sky is clear as it hasn’t been in years. At night one can see the stars.

Yet, Confindustria is in a hurry to resume, even if the news coming from China is not reassuring at all: although Wuhan reopens, Heilongjiang shuts down. The battle against coronavirus feels like trying to empty the sea with a bucket—open here, close there.

Maybe we shouldn’t fight at all, because the war is lost at the start. We should minimize our movements, we should accept that the stuff we used to get high on in the modern era has finally run out.

Those who pay the most expensive price are those who believed the most and continue to believe in human will unlimited power.

Understandably men trample, as they want to take the scepter back into their hands, they want to govern their future as they believed they were doing in a glorious past. But as the virus teaches us, that unlimited power was a fairy tale and that fairy tale is now over.

April 10th

The ANPI (Italian Partisan Association) proposes to make April 25th (Liberation Day) an appointment for democracy. I accept the call and make myself available for what little I can. Will I also sing Mameli’s National Anthem at the beginning of the celebrations? I await April 25th as I waited for Pope Francis’ Easter Mass. Despite my atheism, it did me good to listen to Francesco the other night, in the deserted square. In the same spirit, I will take part in the virtual event on April 25th. The divinity that democrats worship is just as illusory as Francis’ god, but it will do me good to feel proximity with a million people.

April 11th

In via Castiglione, on the Bologna hills, two kilometers from the city center, someone filmed a wild boar with six small wild boars in tow.

In Brussels, the Dutch reiterate that those who need money must sign a promissory note stating that they will pay back. Back in 2015, when it was a matter of imposing the creditor’s law on Greece, Italy agreed with the Dutch. Today Italy would understandably want to avoid the same treatment. But the notions of debt and credit appear to be rather ramshackle today, as insolvency is meant to validate the same trading system. Yet again, there is no alternative.

Speaking of Greece, Stella and Dimitri are waiting for us on the sporadic island in July. For more than ten years we have been renting a small house among olive trees. What will happen to summer, to traveling, to the sea? We carefully avoid the topic, Billi and I. Maybe there won’t be any trips this summer.

April 12th

After Rutte and Hoekstra’s open rudeness, Mrs. Ursula tries to sweeten the pill for the Italians who are very upset about the Dutches’ slightly offensive avarice. Will they grant an unconditional MES? Why does no one mention Coronabonds anymore?

However, everyone agrees over one thing, there should not be a slate clean of the past—I have heard it several times from European negotiators. Why is this slate clean a bad thing for everyone? Perhaps it would be better to give up. “Chi ha avuto ha avuto ha avuto chi ha dato ha dato ha dato scurdammoce ‘o passato simm’e Napule paisà” (Who got it got it, who gave it gave it, let’s forget about the past we’re from Naples my friend). Well, unfortunately the deep wisdom of these Neapolitan verses is incomprehensible to the economists.

April 14th

In an interview published by Il Manifesto, the old socialist Rino Formica notes that we should not believe that surviving at this moment is more important than thinking, as the Latin motto primum vivere deinde filosofari (first live then philosophize) suggests. If we don’t philosophize, Formica wisely observes, we risk not to know what choice to make in order to live.

Marco Bascetta, for his part, always on Il Manifesto publishes a (quite confused, yet intriguing) reflection on the same, slightly modified, Latin motto: primum vivere deinde laborare (first live then work). He rightly observes that there can be no market without life.

Agamben has written several times that in the name of bare life we are willing to give up on life, and another Latin maxim comes to my mind, one I have always preferred to the one mentioned by Formica, that is navigare necesse est, vivere non est necesse. What do we live for when we are no longer able to navigate?

For the second time the President of the United States threatens to suspend fundings for the World Health Organization, because, he says, they reacted slowly and wrongly to the pandemic approach, and perhaps because they even took a pro-Chinese position. He also surreptitiously threatens to fire the most authoritative expert in the whole American health system, virologist Anthony Fauci.

In recent days, some photos came from his country, portraying bags containing corpses, thrown into mass graves, dug for those who do not even have the means to afford a funeral or a burial, right outside the cosmopolitan metropolis that is New York. Many were shocked thinking this to be a consequence of the cursed virus, that is forcing the Americans to renounce a funeral, and the due respect for the deceased.

Mistake.

Those photos are no news, they don’t have much to do with the epidemic. In that country, in fact, those who have nothing and die like dogs are usually buried that way, detained in some prison, in a mass grave, or in the fetid suburb of a very rich city. That’s the normality many wish to return to.

April 15th

Some comforting news: in California crowds of homeless occupy flats and villas for sale, no one will ever buy at this point. Some disturbing news: in Lagos, citizens of some neighborhoods arm themselves to defend their properties from hordes of thieves who, taking advantage of the curfew, steal what they can overnight.

But isn’t this perhaps the same issue, isn’t this due to the fact that in times like these, in times like those coming, private property becomes something labile, weak, fragile? Somehow not straight, oblique.

I read on Facebook: “All this has created such a bad climate. You go out with a mask and gloves for shopping or buying newspapers, if you pay attention, everyone looks suspiciously at each other, and if someone gets too close there is an almost panicking atmosphere of terror. If we get over this virus, will we also get over this behavior? I don’t know. Will we frown at each other forever?”