Books As Bodies

Bodies as books: a conversation with Dora García

Books Are Bodies (They Can Be Dismembered) is artist Dora García’s new work, designed for the spaces of the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome. The project consists of an exhibition, two performances as well as a reading group, and develops a reflection on the notion of censorship and its implications.

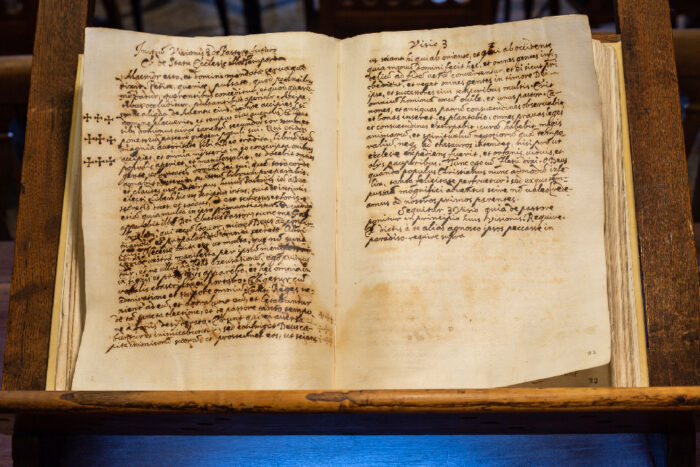

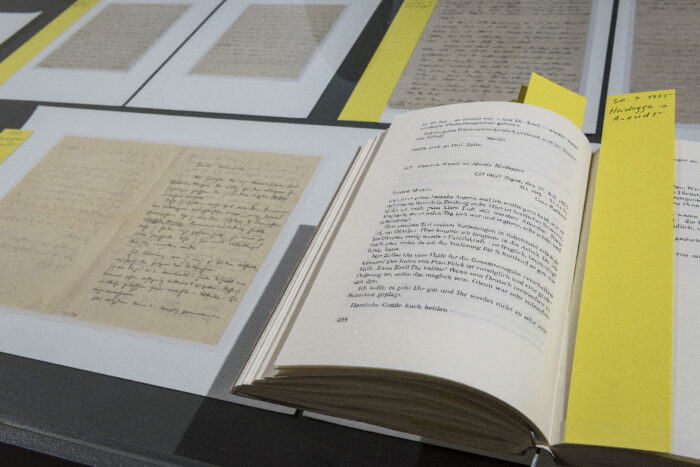

García worked on a selection of censored, erased, dismembered books from the collection of the Biblioteca Casanatense: tracing their connections and reconstructing their silenced histories, the artist analyzed the potential subversion that was recognized within the texts.

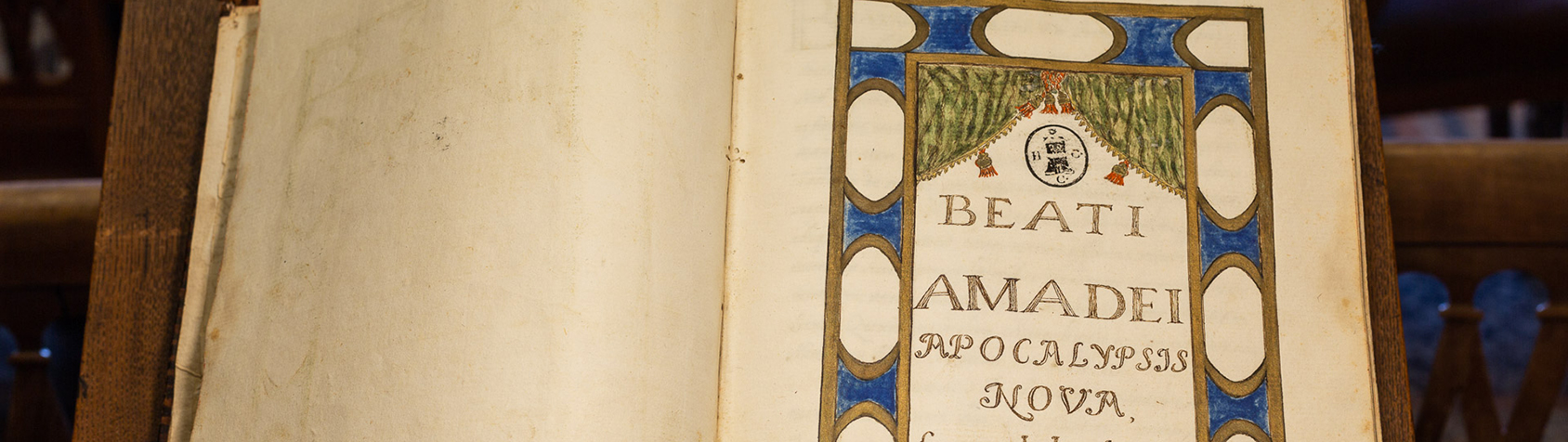

The installation focuses specifically on the volume Apocalypsis Nova, written by Blessed Amadeo da Silva at the site of the apostle Peter’s martyrdom, the Tempietto del Bramante, now part of the Real Academia de España en Roma.

Curated by Sara Alberani and Marta Federici, with Valerio Del Baglivo (LOCALES) Hidden Histories is designed as a platform for site-specific research and artistic production and aims to critically re-discuss the city’s historical-artistic legacy, adopting approaches and methods of decolonial thinking. In this third edition, the focus remains on the public space, a dimension that in Rome is closely connected to the notions of heritage, preservation, restoration, and monumentality, along with its collections, archives and objects that still today are read and valued within a white, patriarchal and heteronormative canon.

Hidden Histories 2022 Trovare le parole / Finding the words takes its cue from an expression by feminist theorist Sara Ahmed in her book Living a Feminist Life (Duke University Press Books, 2016), and focuses on the linguistic dimension as a fundamental space in which to act and declare what is not seen and recognized within society as violent, racist, and sexist. As stated by Ahmed, finding words means naming the problems we are confronted with, “allowing something to acquire a social and physical density by gathering up what otherwise remain scattered experiences.”

Giulia Crispiani: Books are bodies (they can be dismembered) is a work on libraries and censorship, or?

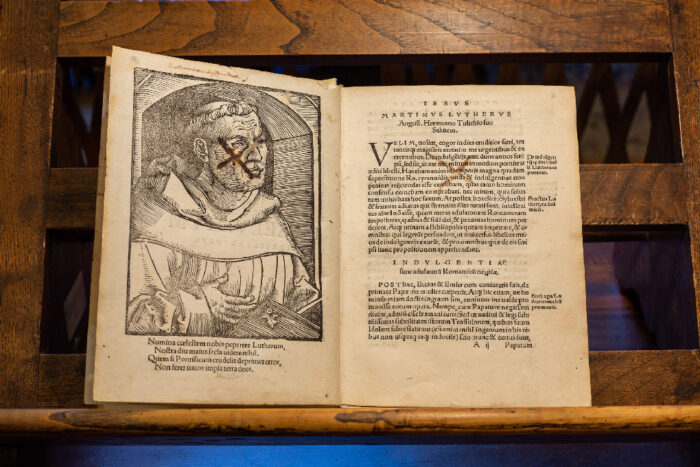

Dora García: No, it is not exactly on censorship. Or rather, it is about more than censorship. It begins with the beauty of any library, the beauty of a specific library—Casanatense, the task of preserving and classifying knowledge—with the books they keep, but also with the symbols of the Earth and Firmament globes and the statue of Thomas Aquinas—and finally, the presence of dissent—the heretic books. What is most interesting about this collection of heretic books is that you cannot cancel content—by scratching it, tearing it off, or covering it—you just create new content.

Could you guide us through your encounters and choices that lead you to this very site-specific intervention? How do you make books become bodies?

I do not transform books into bodies … I wish I could!—I make a reference to the violence of “mutilating” a book—by scratching the surface of the page, by tearing off pages, by crossing over text. We speak of mutilation of books as we speak of mutilation of bodies—the book is damaged, and much more than a surface is damaged—knowledge, ideas, are damaged, and thus transformed.

My first idea upon receiving the invitation was—this place is so beautiful; I should just find an excuse to make people visit it. Then I was made aware of the presence of the heretic books, and how heretic—meaning, contrary to the doctrine, dissident—books were preserved: there is not a section of “forbidden books” in Casanatense—rather, those books are just preserved with the others, spread through the library; which made me think of the story of Allan Poe, The Purloined Letter—if you want to hide something, place it in plain sight. The defense of the Catholic doctrine was made by damaging books and by damaging bodies—for instance, the first “censored” book I was shown was by Miguel Serveto, who died at the stake, so dissident bodies are very much linked to dissident books. My intention is to show books considered dangerous (can a book be dangerous? can you kill an idea?) and how they are hidden (warning the reader), or damaged (making reading impossible). I also include a work of mine from 1999, Ulysses that consists of the “mutilation” of Joyce’s book. A book that was also considered dangerous and that begins with a mockery of Catholic’s mass.

Why have you decided to focus on Apocalypsis Nova in particular?

This was a suggestion of the director of the Academia de España en Roma, María Ángeles Albert de León, who suggested working on this book as the legend says it was written in the Academia and as the Casanatense holds two incunabula copies. I followed her suggestion and discovered a very interesting story, of course. Legend has it that this book was written by Beato Amadeo as a revealed book, a conversation with Archangel Gabriel, at the site where we find now the Tempietto di San Pietro in Montorio—where supposedly as well, Peter the Apostle was martyred—so, quite a thriller! And this supernatural text, written between 1472 and 1475, was conveniently discovered by cardinal Bernardino López de Carvajal in 1502, giving him the legitimacy he needed to postulate himself as “the angelic pope”—not to make this answer too long, let’s say that mysticism is never too far from politics, and this one case stretches into the colonial politics of Spain.

Regarding apocalyptic theories and trends—currently very much in vogue—what do you think is their relationship with power structures and ideologies? (Sometimes lately I even feel they come from very masculine frameworks, I don’t know whether we can say that or if it’s just an impression of mine…)

I started answering this question already above, so to continue here: yes indeed! Even if end-of-the-world mood are as old as the world itself, power structures—which are obviously masculine—benefit from everything—they always win—hopefully not forever. This said, Apocalypsis means revelation and the original one, by (allegedly) John the Evangelist, is one of the most beautiful texts ever written—and it is conveniently manipulated by those wanting to cast themselves in the role of saviors. Also: even if end-of-the-world mood have existed in every decade, I think we have reasons to believe something is really ending and something else is beginning. What ends and what begins, that’s the discussion.

Censorship often happens through a certain kind of physical intervention that remains in retrospect visible and traceable—I must think about defacement and iconoclasm during the Protestant Reformation, for instance—while some other times attempts to lose track through total erasure. What have you witnessed through your browsing? What kind of traces were meant to get lost?

I believe in the case of the Casanatense research, every gesture has left a trace. We can follow every step in each book.

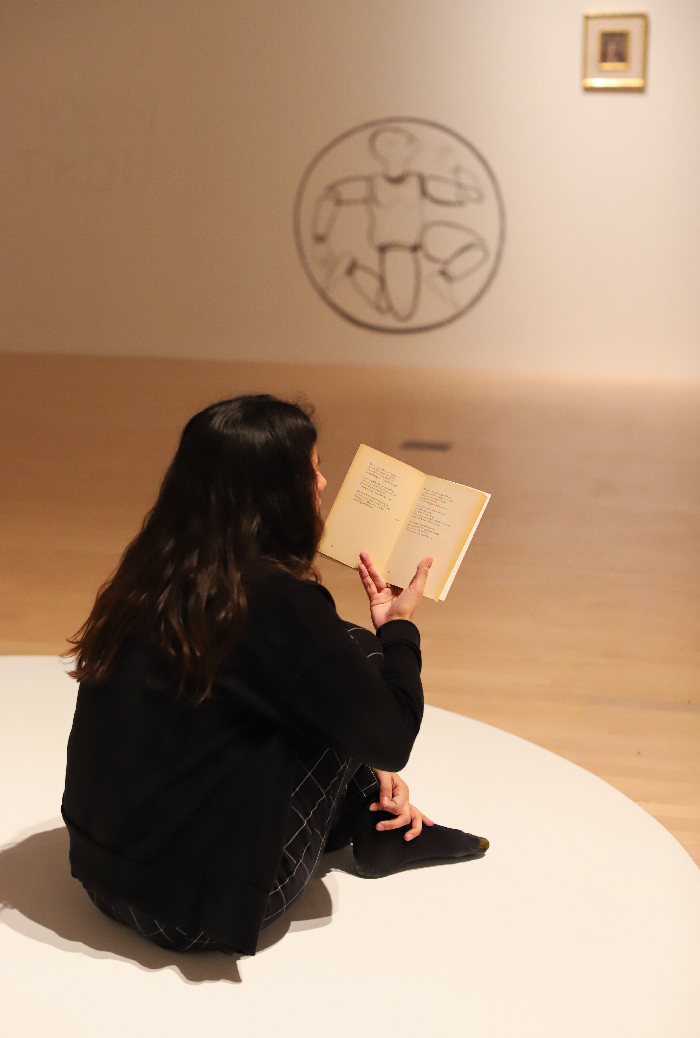

How do you approach reading groups and what do you get out of them? What is the potential of a bibliography?

I like to think of my artistic practice as study—research if you want, but I think study is a more precise word. When I worked on Finnegans Wake, in 2013, I understood the sense of reading groups. In fact, individual reading, in silence, is a XIX century invention; XIX century novels created a new type of readers. But before that, and probably it will be so in the future, reading is a collective endeavor, the text a way of creating community. And this is what interests me in reading groups. What is the potential of a bibliography? I am not sure how to answer that, but I suppose it’s about creating the gravitational field of every text, and that is very interesting, considering that a text—a novel, an essay, poetry—never stays the same, but it is constantly changing as new generations read them—interpret them.

Much of your practice is word-based. Where do you find your words and how do you leave them behind for others to be found again?

Again, I am not very sure how to answer that. I find my words without any effort, I encounter them, I bump into them, for me the world is made of text. This text-world is not static, but in permanent movement, evolution, metamorphosis, so I do what everyone else does, everybody is affected by this infinite text—that is internet, for instance—and contributes to it.