Black Digital Currents

On gendered and racialized currents of digital culture and technology

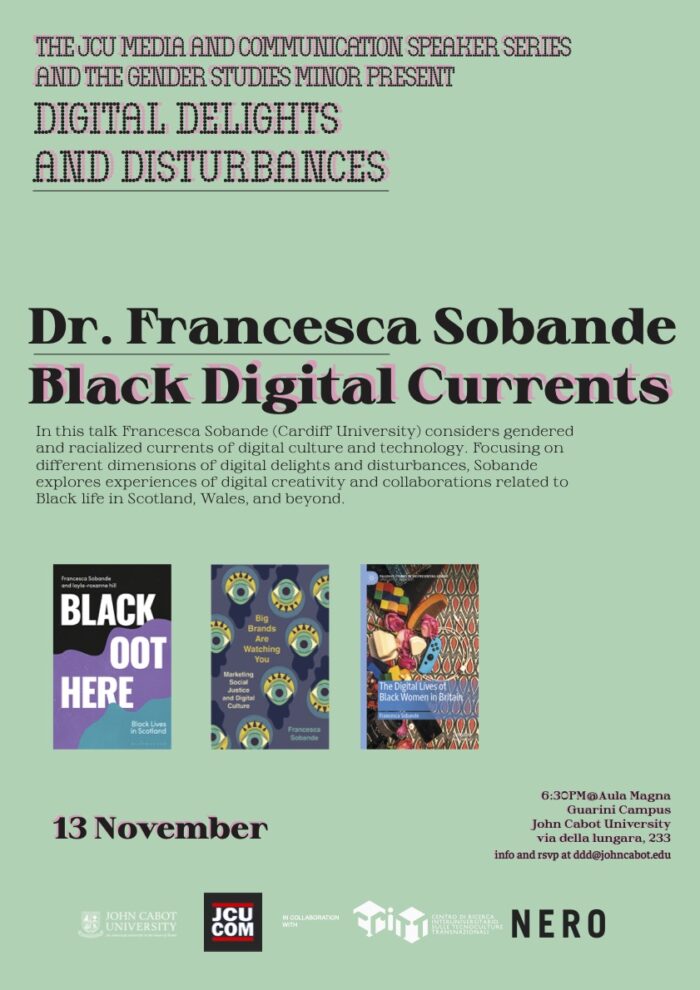

The Department of Communication and Media Studies and the Minor in Gender Studies at John Cabot University welcomes Dr. Francesca Sobande for the public talk Black Digital Currents, as part of the Fall 2024 edition of the event series Digital Delights & Disturbances (DDD). This event will take place on November 13 at 6:30pm in the Aula Magna Regina (Guarini Campus).

This talk considers gendered and racialized currents of digital culture and technology. Focusing on different dimensions of digital delights and disturbances, it draws on experiences of digital creativity and collaborations related to Black life in Scotland, Wales, and beyond. The talk addresses some of the possibilities presented by digital forms of creating and communicating as part of work rooted in Black life, dreaming, and archives.

The DDD Event Series is organized and sponsored by the JCU Department of Communication and Media Studies, in collaboration with NERO and CRITT (Centro Culture Transnazionali). Dr. Sobande’s talk is co-sponsored by JCU Gender Studies Minor.

Make sure to RSVP using this link. More info at [email protected]

How do we become food for the market on social media?

Francesca Sobande: What is posted and shared on social media spans a wide range of topics and tones, as well as numerous different formats and (in)formalities. However, many social media sites are strongly associated with promoting public images and impressions of the perceived “private” lives of people. Additionally, much social media activity stems from platforms that were designed to facilitate forms of advertising, branding, and commerce—essentially, social media = (re)production and consumption.

All of this means that beyond the descriptive term “social media” lies markets. What people post and share on social media, whether they intend for it to or not, can contribute to forms of capital and profit-making, even if such people themselves are not the beneficiaries of it. Without individuals using social media platforms, the platforms themselves would not exist. So, in a sense, we become food for the market of social media from the moment we choose (or, in some cases, are forced) to participate—consequently, feeding the demand and online content churn that keeps social media going.

When considering all this, it is helpful to turn to the striking words of Toni Morrison (Knopf Publishing, 2019) in The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations: “We become ‘ads’ for ourselves under the pressure of the spectacle that flattens our experience of the public/private dichotomy.” Often, nowhere is spectacle as strong as on social media platforms, which are designed and function in ways that feed marketing.

It would be misguided to portray social media as an autonomous imposing force. Ultimately, social media both influences and is influenced by the desires and demands of (some) people. This includes those of individuals who own certain online sites, platforms, apps, and digital corporations, enabling them to determine some of the ways that social media functions and who and which political positions are particularly platformed. We’ve seen this repeatedly in relation to Elon Musk’s ownership of X (formerly known as Twitter).

Can we emancipate ourselves in any way?

There are always ways of undertaking emancipatory actions, but it’s important to recognise that an action which may be or feel emancipatory for one person, may not be an action that is for another.

For example, some people’s decision to disengage from social media may feel freeing to them and, depending on the context, may even be deemed a resistant action by others. Yet, due to systemic inequities and distinct disparities between people’s access to the internet and technology around the world, the choice to disengage and disconnect from digital spaces can be a luxury afforded to people with the material conditions that enabled them to connect in the first place. This means that it’s important to avoid overstating the emancipatory potential of certain forms of digital disengagement, disconnection, or as it is sometimes termed, detox.

In my book Big Brands Are Watching You: Marketing Social Justice and Digital Culture (University of California Press, 2024), I looked at how some brands use the language and framing of being “anti-social media” in ways that may benefit their image and boost their visibility rather than aiding substantive changes to the state of social media/Big Tech. As part of that work, I’ve also continued to research the approaches of brands that appear to promote paradoxical ideas about social media, such as by them logging off while continuing to strategically engage influencers and the online creator economy.

In other words, emancipation from the oppressive impacts of social media requires much more than individual consumer choices or the (anti)social media strategies of brands. Truly emancipatory actions must address the effects of structural power regimes related to capitalism, global hierarchies, and much more, including by working to decentralise Big Tech’s control.

How morality and social justice are incorporated into marketing strategies and fetishised?

Marketing loves slogans and soundbites. If there is the opportunity to create a sense of buzz by tapping into discussions about topics that are trending online and receiving attention in society more broadly, brands often find ways to try to do just that. At times, these dynamics have contributed to brands commenting on issues of morality and injustice in breezy and flippant ways that trivialise oppression such as anti-Black racism and police brutality.

While brands may comment on some issues of morality and injustice, they may also actively avoid speaking about and taking a stance on others. As I look at in my work, in the UK and the US, structural whiteness shapes which issues of injustice receive vocal responses from brands, as well as shaping their loud silences in response to others, including apartheids and genocides.

During what is often referred to as “the summer of 2020,” we witnessed brands make statements and social media (re)posts sparked by the Black Lives Matter (BLM) and racial justice action that followed the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. While some brands went beyond one-off gestural communications, they were few and far between. Sometimes distracting from and diluting the messages of organisers and activists, other brands were quick to create representations that, tenuously, alluded to issues of racism or invoked illusionary ideas related to anti-racism. Basically, the fetishisation of (anti-)racism and issues of injustice in the marketplace involves promotional culture which repackages public relations rhetoric as social justice-oriented strategies.

Whether it’s in the form of influencer culture colliding with the online content of social movements, or the pithy yet perfunctory press releases of brands, morality and social justice are incorporated into marketing strategies and fetisished in many ways. In collaboration with Marcel Rosa-Salas I’ve looked at how the idea of intersectionality (the interconnected nature of systemic oppression such as racism and sexism—as outlined by Kimberlé Crenshaw) has been commodified and marketised. We’ve critically analysed how brands and the marketing industry at large reframe intersectionality to position it as a market segmentation tool—fundamentally treating intersectionality as a lens through which continuing to profile and categorise “consumers” by their perceived intersecting identities and the associated forms of oppression they are (or are not) impacted by.

In The Anti-racist Media Manifesto (written in collaboration with Anamik Saha and Gavan Titley) what kind of media do you envision?

In the book we envision an anti-racist media future that is committed to obstructing the lucrative circulation of racist discourse. This is a future which also involves media organisations and practitioners working to ensure that what they create is designed, produced, and shared in accessible ways, combatting the centralisation of media power and supporting sustainable and multi-lingual forms of journalism and digital storytelling, locally and nationally.

Can you tell us a bit about on your broader research on Black lives and Black digital organising and how do Black feminist media studies inform your research and writing?

My work has included focusing on The Digital Lives of Black Women in Britain (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020) and, as part of collaborative work with layla-roxanne hill, focusing on being Black Oot Here: Black Lives in Scotland (Bloomsbury, 2022). This has involved accounting for the changing landscape of digital culture, and media more generally, in Britain, while also considering the specifics of how Black people’s experience of that is influenced by regional, national, and international dimensions of Black diaspora(s). In the context of Britain, this also means naming how (dis)connections between its constitutive nations affect the realities of being Black in different parts of it.

My continued work with layla-roxanne hill has involved co-authoring the free graphic novel Black Oot Here: Dreams O Us, illustrated by Chris Manson and translated in Scots (by Lesley Benzie) and Scottish Gaelic (by Naomi Gessesse). A related animation, co-created with Leeds Animation Workshop, features music by Nathan Somevi. Digital technology considerably contributed to those processes of co-creation (what I feel is a “digital delight”), as those collaborations occurred in predominantly remote and asynchronous ways.

Black feminist media and music studies significantly inform my research and writing. Most recently, I’ve been doing work on the construction and cultural memory of “alternative” (alt) music genres, with a focus on the relationship between Black creative culture and certain “alt” rock genres and sub-genres. As part of that, in collaboration with Jenessa Williams, I’ve been continuing to look at elements of nostalgic narratives surrounding emo (also known as emotional hardcore/emocore). I’ve also been reflecting on the significance of a series of recent online commentaries on topics such as: (1) the tongue-in-cheek metalcore sub-genre “baddiecore,” (2) Megan Thee Stallion’s collaboration(s) with the band Spiritbox, and (3) the relationship between (nu-)metal music and the world of The Vampire Chronicles (e.g. the 2002 film Queen of the Damned and the forthcoming third season of the TV show Interview with the Vampire).

As is discussed in more detail in my forthcoming book with layla-roxanne hill, Look, Don’t Touch: Reflections on the Freedom to Feel (404 Ink, 2025), Black feminist work informs my approach to researching and writing about all of that. This includes my focus on the interconnections of blackness, gender, class, and capitalism, which contours perceptions of “alt” rock music, aesthetics, and their origins, as well as shaping who/what materially benefits from it.