Birds of Paradise, Birds of Prey

A dramatized act of writing curated by Nick Mauss

“The curtain with its flight of birds of Paradise blew out again. And Clarissa saw—she saw Ralph Lyon beat it back, and go on talking. So it wasn’t a failure after all! it was going to be all right now—her party. It had begun. It had started. (…) they <guests> went on, they went into the rooms; into something now, not nothing, since Ralph Lyon had beat back the curtain”.—Mrs Dalloway, Virginia Woolf

Following one of the many interpretations, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway is a tale of an artist’s struggle to defy death through a careful mixture of select elements resulting in artistic illumination, or the flash of an ideal. For a brief moment, marked in by the fluttering of the patterned curtains, the guests invited by Clarissa Dalloway, come together in a perfect, almost magical assemblage. In the book, this moment of divine creation results in the party’s success and allows for a glimpse into the eidos.

Nick Mauss’ Bizarre Silks, Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts, etc. is a similar attempt. Like Clarissa Dalloway, he does not seem concerned with presenting his objects of curatorial choice in dramatic juxtapositions. Rather, he leaves room for the beholder’s mind to roam the constellations he arranged and seek for meaning—the elements are already there, waiting to play the role of parts of a larger composition. The constellation Mauss confronts us with unfolds in different modes of being and resonating in space. The artist-curator sets the scene and allows its viewers to float and construct the connections themselves, lightly hinting at the moments of possible consolidation of meaning.

Rather than focusing on the properties of media, Mauss has often reiterated his practice’s interest in space: “The question for me became not so much finding a medium, but finding a space I would like to work within. The first space that I found (…) was the space of the page, rather than the space of painting or sculpture. The space of the page could easily become a space of the notebook, letter, the space of annotation, drafting and dedicating. Later also, the space of the book, with multiple plates side by side, space of margins, screen”.

An interest in exhibition making, in exploring the ways of arranging objects and concepts in space, seems only natural as an elaboration of Mauss’ approach to a page as a two-dimensional plane. His contribution to the 2012 Whitney Biennial where the artist confronted objects sourced from the institution’s collection with an architectural reconstruction of Christian Bérard’s intricate velvet room, marked a clear step beyond that. Later Mauss incorporated a fourth aspect—time—in his spatial arrangements. The most prominent (though nor the earliest) example is Transmisssions at the Whitney Museum of American Arts—a carefully researched exhibition centered around the previously imperceptible, yet dense relationships between modernist ballet and avant-garde visual arts of mid-century New York, taking performance as one of its points of focus.

Mauss’ further self-exegesis explains how he adopted a uniform plane in order to encode ambiguous messages: “I used the idea of a blank page as an intimate plane of encryption of which any number of discontinuous or conflicting images, emblems, articulations or shadows of ideas, could be made to register side by side or over one another and presented in this vulnerable in-between or not-yet-space”. This type of spatial thinking also structures Bizarre Silks, Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts, etc. at Kunsthalle Basel which plays out as a dramatized act of writing.

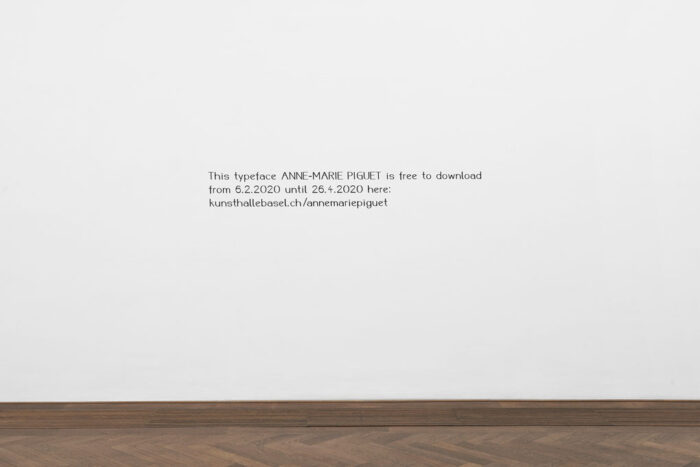

The exhibition starts prior to us entering the building—on the Kunsthalle’s website—where Bea Schlingelhoff makes available a typeface named after a Swiss Second World war heroin, Anne-Marie Piguet. Both the concept and the work itself transgresses the institution’s physical walls, and as a gift to the audience, and through writing, becomes interwoven in its users’ daily lives.

In the first room Bizarre Silks… opens with Ray gives a Party (1955), Ray Johnson’s photomontage compilation, telling a tale of a curious festivity, containing (among other odd items) portraits of invitees in animal costumes. This piece sets the mood and announces the exhibition as a banquet with an unusual assortment of guests. Those assembled at the Kunsthalle, are works by artists coming from a vast array of spatial and temporal contexts, which weave into a string of narratives.

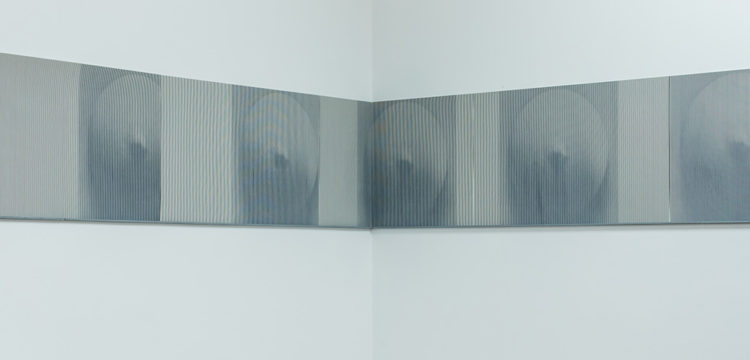

This is followed by a porous curtain resembling a mesh, an element of scenography that beckons the public further into the Kunsthalle’s interior. In the five following rooms, the exhibition will unfold in five subsequent acts. Next to it sit Ketty La Rocca’s two black PVC sculptures: J (1970) and Comma with 3 dots (1970), rescaled black lettering on two opposing sides of a white pedestal. In addition, in this first exhibition room, Mauss introduces us to Rosemary Mayer, the author of two elaborate baroque textile compositions celebrating female figures of power: the Roman queen (Galla Placidia,1973) and the ruler of Greece’s Lemnos (Hypsipyle,1973). Purple, blue, orange silks and gauzes, shaped into delicate monuments to lives turned into myths resemble elaborate ancient hairstyles, or costumes from before millennia. As echoes of the human body they also anticipate the next act.

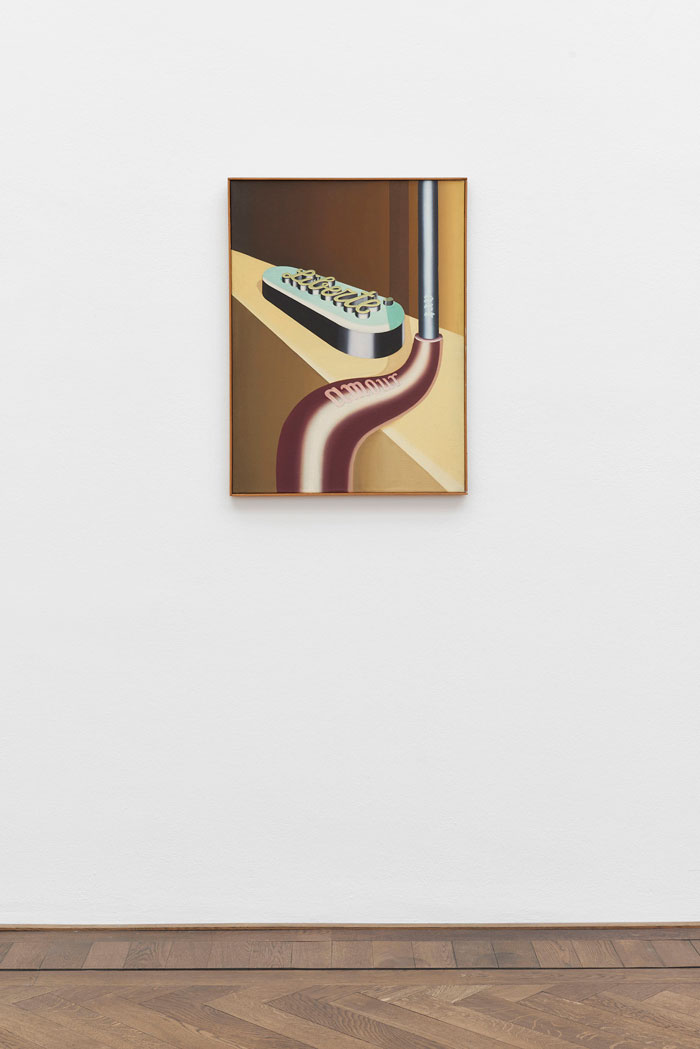

Referencing the thin boundary between animate and inanimate is Konrad Klapheck ’s Liberté, Amour, Art (1964) depicting a mechanical composition: a yellow plane in the background accommodates a configuration of pipes with the titular liberty, love and art written on them. The artist portrays words denoting strong, emotional terms as elements in an intricate yet cold, device. The notion of an object that motionless yet sentient is explored in Georgia Sagri’s series of wall stickers (Deep Cut, Open Wound, Fresh Bruise, all 2018). The work’s palette ranges from deep crimson, to plum to ochre, its uneven outlines seem to expose what lies underneath the surface of Kunsthalle’s walls: layers of gruesome, human or animal-like insides. The promised neutrality of the white cube thus challenged by an artistic gesture, which presents the building as a living organism that nonetheless bends to the artists’ and curators’ will.

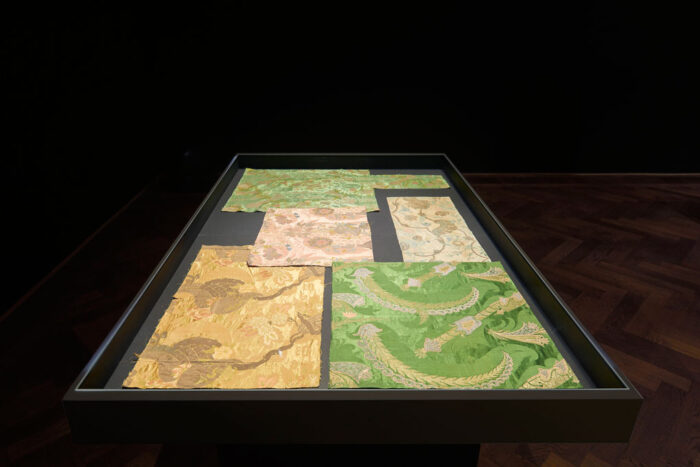

The third act is where the exhibition’s title of the show is finally explained. The darkened room is at the heart of the dramatic sequence—it hosts cases containing the eponymous “bizarre silks”. Colorful and rich, this type of fabric was popular in 18th century Europe. In one interview, Mauss described them as characterized by “anomalous design, which often included metallic and polychrome threads. For a long time it was impossible to determine where they were made. United in their departure from established design vocabulary alone, they addressed a taste for the exotic. (…) bizarre silks were the first examples of autonomous work by designers in textile production, suggesting that this short-lived genre, which broke with all rules of composition, harmony and purity, enabled unprecedented artistic ability in European textile production”. The silks’ designers, merged ornaments from Japan, India and China with quotes from contemporary, baroque scrolls and spirals, creating mesmerizing semi-familiar, asymmetric compositions.

The textile items are neighbored by Edward Owen’s Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts (1968–70). Another component of the exhibition’s seemingly cryptic title, the work is a mute, oneiric filmic collage mixing images of the artist’s mother with faces of supposedly random people, symbols and trivial objects. The “imaginings” and “facts”, key ingredients of the work’s loose narrative, impose themselves compelling the viewer to weave a story in their head. The curator emphasizes the narrative potential of chance encounters—and the fact we cannot prevent ourselves from imagining connections between the subsequent images. The longer one looks, the closer one feels to solving the film’s mystery (and more reassured we are that such a mystery exists).

The narrative potential of contrasting form with subject matter is central to the next “spatial act” taking place in the next room, where we find ourselves in a living space à rebours. Paintings of bathers by Paul Cézanne, in nocturnal blues, browns and blacks, repainted in negative colors by Megan Francis Sullivan, surround the room’s centrepiece—a black and white bed by Robert Morris. “It would be difficult to achieve erasure with a single thermonuclear device, given the present state of technology. (…) More practical and more certain would be the utilization of several dirty, fairly high megaton yield devices. (…) the circulating wind would distribute the radioactivity over the surface of the earth and all life on the planet would cease”—reads the cruelly methodical text on the pillowcase. The bed is negligently covered with black and white cloth, patterned with bones and bombs. A sense of danger and unease lurking underneath a familiar, friendly shape appears again in Gretchen Bender’s TV Text and Image (PEOPLE WITH AIDS) (1984)—two screens, on which a blunt, dark caption is contrasted with featureless, decontextualized broadcast, news snippets and commercials. The contradicting visuals provoke a cognitive dissonance—an abundant source of stories one tells oneself to justify one’s deeds.

Echoing Ray Johnson’s photographic collage, the last room also plays host to a collage anthology—this time, the scrapbooks produced by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s (1964–70 and 1979) using the dada-inspired cut-up method of combining images from different registers in one “page-space”. Referencing theatre again and adding to the Verfremdungseffekt this fifth and final act is also where Mauss’ own work shines best. Six Tresholds (2020), portals covered with Mauss’ signature drawings are displayed across the room. Monumental yet delicate, the vertical canvases alter the spatial surroundings and set the scene for the grand finale: the one of death and rebirth. The former is represented by Anton Perich’s Victor Hugo Rojas (1978), a shaky video documentation of Rojas’ performance involving the destruction of his own portrait made by Andy Warhol. The rebirth is represented by three reenactments (held in collaboration with Amanda Friedman and the Estate of Rosemary Mayer) of February Ghosts (Monoceros, Auriga and Orion) (1981/2020)—wooden and cellophane installations meant as hypothetical representations of celestial bodies.

“Still, life has a way of adding day to day”—says Mrs. Dalloway’s narrator. Just as stars had been grouped into constellations, so are random facts being joined into chains of cause and effect in order for us to make sense and navigate the future. In Bizarre Silks… the objects lie in wait to reveal themselves as a meticulously orchestrated constellation. While Mauss’ arrangement might have seemed impossible, once materialized, it feels it was bound to happen.