Beyond Inner-Outer

Some proposals from the feminist group Nemesiache

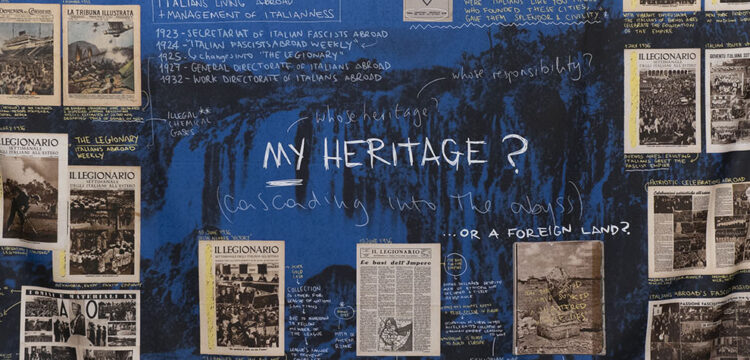

Our truths flow together with the waves aims to explore the concept of self-image in relation to landscapes, focusing on the intersection of gender and identity. It draws inspiration from the artistic path of the Nemesiache, a feminist-artistic group based in Naples from the 1970s on. Consisting in exhibitions, workshops, and online publishing, the project’s research is centered around the exploration of women’s condition as a cosmos, using various artistic mediums such as dance, music, rituality, and poetry. Our Truths Flow Together With the Waves will be hosted at the Italian Cultural Institute in Copenhagen from July to August 2023. Additionally, Casa Morra, Archivi d’Arte Contemporanea in Naples, will host the project in October to November 2023.

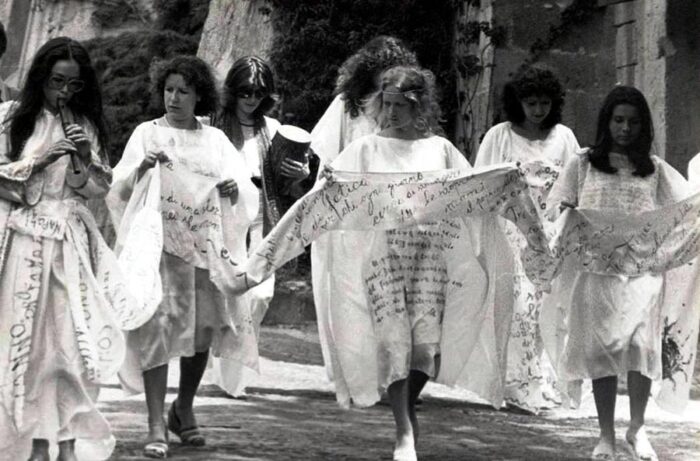

The day some of the members of the Nemesiache broke into Santa Chiara Church, in the old neighborhood of Napoli, walked together down the aisle and randomly posed around the altar, will never be allowed the status of historical fact, but that moment did transform the narratives, the history of that church, beyond any other permanent or structural intervention. Those simple actions consisting in restored behaviors like walking or dancing and marked both by an aesthetic and an actual thinking, reshaped the narratives unscripted in a frame which restrains women’s bodies and enhances the mind-body dualism. By avoiding any form of orality and performing an everyday-life behavior, the Nemesiache didn’t reclaim a space, but radically turned it into a space of freedom and joy, opening it to a dimension of multiple values. Space and narrative are interchangeable concepts: space, as narratives, needs to be heard and it hears us so.

The radical feminist path of the Nemesiache, the group founded by Lina Mangiacapre in Naples in 1970, for more than fifty years has been combining artistic practice with feminist struggle. After attending Roman feminist circles in the late 60s, such as Rivolta Femminile led by Carla Lonzi, in 1969 Lina Mangiacapre went back to her native city and, together with her sister Teresa founded the group, motivated by the desire of imagining new practices of living together and shaping a new patriarchy-free culture.

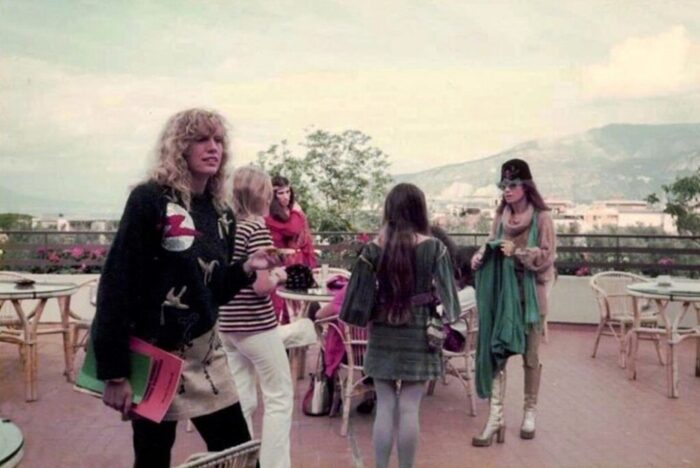

The word “Nemesiache”, coined by Lina Mangiacapre, refers to the Greek myth of Nemesis (the name that identified Lina Mangiacapre from 1969 on), the goddess who enacts retribution against those who succumb to hubris and social injustice. The other members of the Nemesiache, followers of Nemesis, were inspired by ancient Greek mythology and legendary nymphs, such as the naiads of the freshwater, the dryads of the trees, and the oreads of the mountains. The components have changed throughout the decades and the group has been animated by up to twelve women at times, but the core of the group consisted of at least five people. Considering the body as a cosmos, the Nemesiache explored and investigated the complex feminine reality through a multidisciplinary practice, which included performance—with a specific focus on ritual, dance and music—cinema, poetry, painting and sculpture activities, comics, political and philosophical speculation.

By providing a number of proposals conducted by the Nemesiache in the 70s and 80s, this essay aims at highlighting an artistic path that came out of necessity and shaped both a physical and a symbolic space where neglected stories and roots are allowed to emerge. In order to abandon simplistic and linear Western logic, considered by the group the core of the patriarchal ideology, the Nemesiache recurred to the body and its relations with the landscape energies as a valid means to explore and express self-identity.

The Nemesiache expressed their refusal to build an artistic path which does not affect real life and marked a radical distance from the contemporary conceptual activities of the 70s and the following artistic scenarios in Italy, so little committed in political and social terms. In the last two decades of the 20 century, Napoli has been crossed by numerous male personalities—such as Joseph Beuys, Hermann Nitsch, Andy Warhol or the members of the Italian movement Transavanguardia—who held the notion of artist as a master, and did not question the problem of individuality concerning the Modernism. In this regard, the Nemesiache asserted their art as a result of horizontal processes and never presented their works as the outcome of individual practice. In that sense, the Nemesiache did blur the boundaries between personal and collective struggle: every member of the group never acted as a single artist, but as a “nemesiaca”, differentiating also from most of the other simultaneous feminist groups.

In 1980, Lina Mangiacapre wrote a poem dedicated to Andy Warhol, where she refused every form of art as pure entertainment or speculation, considering his interest in gender theories as unavailing in the Neapolitan context:

A poem to Andy Warhol

This Avant-garde

This Avant-garde

in slippers

all it does is

trivial gestures and phrases

playmates and champagne

Only you, as no else, could

carry the whim

of inebriation

And, as usual

Napoli is selling off.

Dear Warhol, today we do not understand

the reason behind the gunshot from

Valerie Solanas,

in that gunshot and in the reasons why she suffered.

Avant-gardes shouldn’t get shot

but we just need to wait for them to…

I am sorry Leopoldo, you, like Napoli

disguided, misinterpreted

by those who intend the mind as the only means [1]

Typical of the Nemesiache’s path is the double struggle for women’s liberation and the condemnation of the downgrading of Southern Italian cultures (still a crucial concern, in Italy). In 1981, on “Quotidiano donna” [2] Lina Mangiacapre remarked the importance of the Mediterranean roots on the raising of a feminist consciousness in Napoli:

“If feminism means criticism and condemnation of every form of oppression, right from the beginning, in Rome or in Milan, for me it was necessary to denounce the racism of the “North” against the “South”. [Even in the feminist circles] the threat was about repeating the same oppression of male culture, by considering the Southern women as the ones who didn’t develop any form of consciousness, like it happened during some of the first reunions. In those moments, my blood pulsed through my veins and I wanted to shout: “I’m a woman from the South and I don’t let you estimate my conscience, speak for yourself!” Or the boredom of some reunions on which women used to compare their consciousness with the male one. I kept wondering: “stop it! Are we that uninterested in us not to say anything on ourselves, on our desires, within us? The men, hounded out of the door, used to back in through the window, colonizing our whole imaginary. […] If the Roman movement, seeking the streets, the public protests and manifestations, fought on an external level in belief of the ancient Roman roots, we, as followers and daughters of the Siren Parthenope, rather investigate the origins and the rituals of our Magna Grecia. Avoiding any form of power, we have searched for our actual strength. […] The need for love and art belongs to the whole history of Napoli. The Roman feminist struggle connects to the glory of the capital, the Milanese feminist struggle, and the other Northern feminist circles so, are connected to the analysis. But Italian history is composed by others roots too, and our movement showed them.” [3]

In 1974, in response to a letter sent by a young woman from Palermo, Angelina, the Nemesiache wrote: “The women of Southern Italy come from a reality, a history, that presents different forms of oppression, therefore the Southern women developed a different way to react.” [4] And yet, “The reality of Napoli, the intricate and complex condition of Southern women, cannot be interpreted, or even rearranged, through the analysis of externalized or generalizable relations. Here, there is something that has been undisturbed: the depth of the ego, an overwhelming ego that cannot be undermined by any social frustration.” While most of the other Western feminist groups struggled for labor rights and social empowerment, the Nemesiache aimed to create a new dimension, a space where to explore reality and its complexity, remote from the oversimplified cause-effect logic. The Nemesiache’s first Manifesto, written in 1970 and published two years later, by aiming to imagine and shape a space where exploring the female inner desires, voice, needs and creativity, suggested that space and narrative are not concepts, but realities, and they are interchangeable too. In such a contest, the human body -considered by the Nemesiache as a constellation that manifests itself through dance, music and rituality- plays a key role in their consciousness raising, so called psycho-fable. Again, if bodies are at the core, the dimension of space becomes central in their practice.

The dimension claimed by the Nemesiache refers to the establishment of a space, which takes shape while it explores both individual and collective subjectivity, towards a body-rooted poetry by virtue of the recognition of a physical basis of human interactions. The forms of the body and interactions are open, as are the forms of poetry. Both interactions and poetry are hardly decipherable to Western logic: the Nemesiache’s earliest performance and movie structures did not follow linear sequences or closed plots: their artistic path is devoted to a process of image-thinking, in contrast to simplifications of objective categories, that started to one such line of thinking in the West.

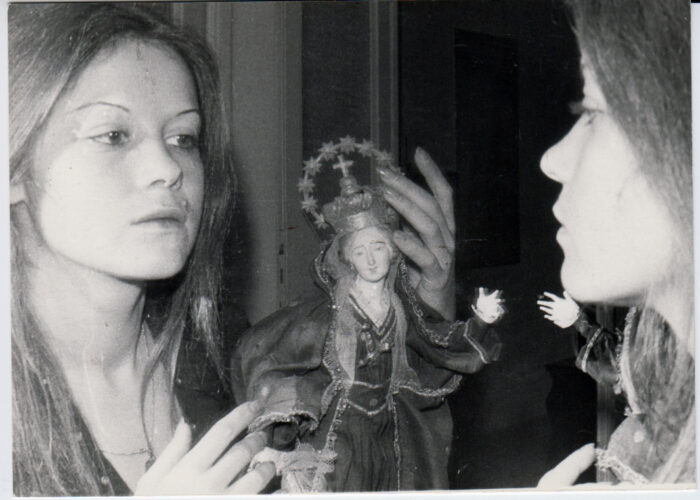

The group’s first performance, Cenerella (Cinderella), staged in Naples in 1973, is a re-writing of Cindarella’s story, which refuses a stereotyped and unified portrayal of the main character: Cinderella is here introduced as a polyphonic woman, who falls into passion, desperately seeks for poetry, freedom and self-expression. It is no coincidence that the play presents the Western founding philosophical fathers (Aristotle, Plato and Socrates) as the main obstacles to Cinderella’s liberation. Cindarella turned into a movie in 1977: in that case, the Nemesiache showed the slogan Inventeremo e creeremo la nostra lotta, come la nostra sessualità, come la nostra cultura (We will imagine and shape our struggle, along with our sexuality, along with our culture). The same statement was also present in the performance Antistrip (= Anti-streap, 1976), recorded and converted into a video in the 80s. Antistrip overturned the performative axis: in a regular theater context, the behaviors concern the performative frame and do not attach to social structures. Since the Nemesiache believed in performativity not as representation, but materialization and evocation of the real, [5] in Antistrip the undressing does not represent but means their own way to explore sexuality through playing: “For us, erotism is a play: once we play, we achieve another sexuality: our own”. [6]

Given the above, the stage becomes a liminal space where to bring to life the hidden dimensions of identity. The performance, transforming a former condition, is a means to change a status, it shapes the former narratives and territories: in the Nemesiache’s performing activities, as it happens in the field of rituality, the efficacy element is dominant over the entertainment. However, while communities usually resort to ritual for establishing and maintaining hierarchy, the Nemesiache’s aimed to modify a pre-established social order by proposing different ways to explore the cosmology of the female body. If stage and life come to coincide, the performing space has both a symbolic and an actual value.

Feminist movements did not underestimate the value of space as materialization of the encounters: in that sense, the field of publishing was meant as a political commitment in the space shaping process. In the late 80s, the Nemesiache launched “Mani-Festa”, a journal devoted to feminist film and art criticism, advertising, interviews, poetry and comics. Although “Mani-Festa” mainly contained cultural contents, every issue included contributions by everyone who wanted to share inner creativity, in the form of poems. Unlike many other feminist journals, which have been collecting testimonies and articles reporting political thinking, the Nemesiache’s journal did not work as a space of the encounter only but as maps of desires.

Some of the 20 century feminist practices deconstructed the primary binary logic, which intended geography in term of configuration of material forms or as a mental or ideational representation, and provided a new imaginary to connect space and perception. By placing the body at the core of their path, the Nemesiache opened a new dimension where to combine the real and the imagined, mind and body, consciousness and the unconscious (through the psyco-fable), everyday life and unending history, potential and real. Beyond any dualism between the reason and the desires, bodies and voices, one can shape a “Third Space” that combines the potential with the real and normalizes desires. In that sense, narration and space become the same reality.

All bodies and all voices are shelters of inner spaces, what if in and out come to coincide?

Thanks to Reading Aloud, here you can listen to the audio version of this text.

[1] Mangiacapre, L. (1980), A poem to Andy Warhol, Archival document in the Nemesiache’s Archive, Naples.

[2] The feminist magazine “Quotidiano Donna” (1978-1982) was conceived as a weekly journal in 1978, but the editorial board turned it into a newspaper in 1981.

[3] Mangiacapre, L. (October 16th, 1981), I covered my beauty with darkness, in “Quotidiano Donna, no. 23.

[4] The Nemesiache (1974), Letter to Angelina, Archival document in the Nemesiache’s Archive, Naples.

[5] The Nemesiache, If Within Several Ideologies One part of Reality in Not Accounted For”, Archival document in the Nemesiache’s Archive, Naples. Also in: Damiani G. (2022), Ritual and Display, Amsterdam: If I can’t Dance, pp. 59-62.

[6] Mangiacapre, L. (1980), Cinema al femminile. Padova: Mastrogiacomo – Images 70, p.15.