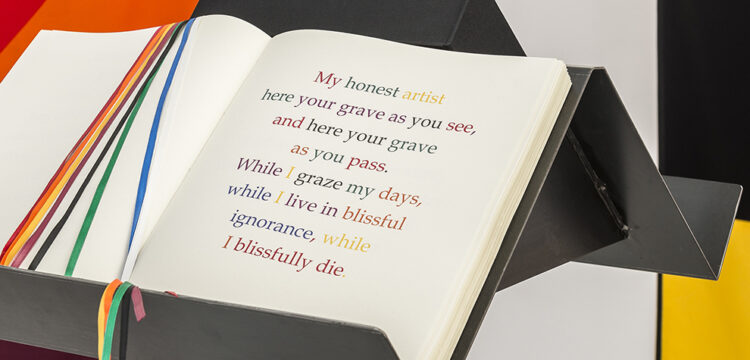

Between Presence and Absence

A conversation with Margherita Landi, from “Dealing with Absence” to “Landi’s Cube”

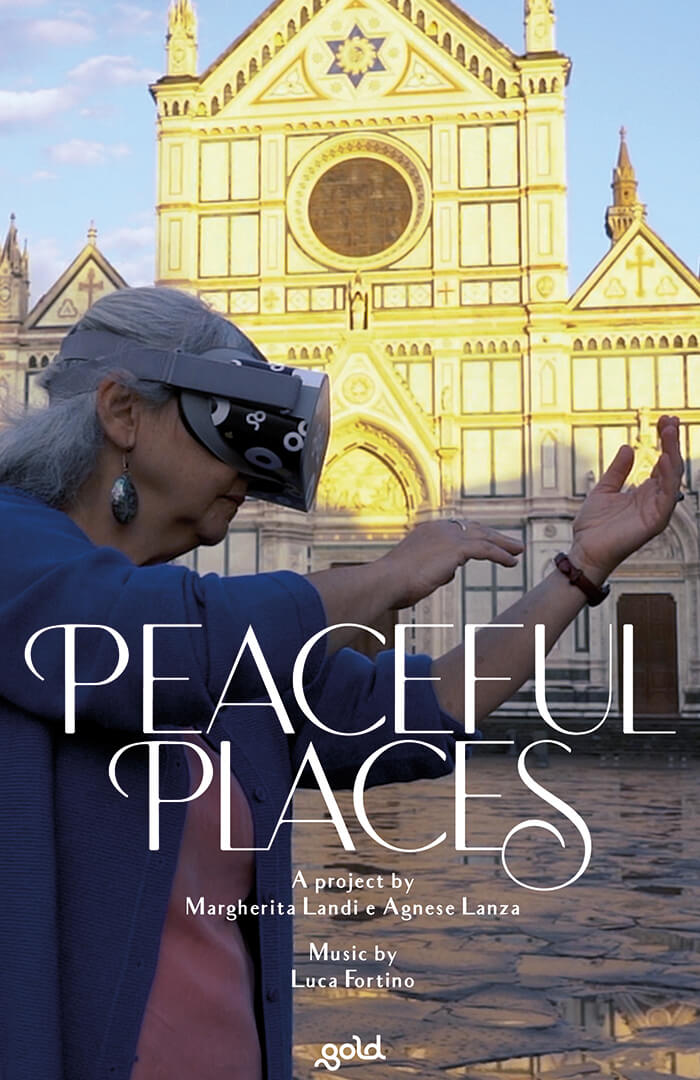

Dancer Margherita Landi continues her practical and theoretical exploration in the realm of Virtual Reality, leading to two dance projects in collaboration with Agnese Lanza. These projects were featured in technology and theater festivals, including Peaceful Places (awarded the 2021 Auggie Award for Best Art at the AWE – Augmented World Expo in the USA) and Dealing with Absence (recognized for Residenze Digitali in 2021). Both projects delve into the emotional states evoked by images within the dancer’s or user’s VR headset.

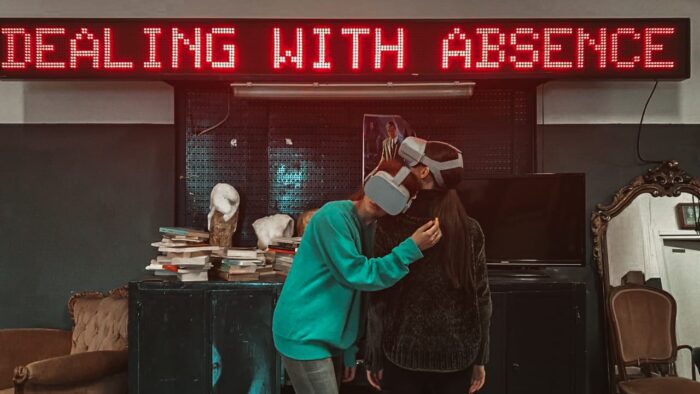

Peaceful Places is a virtual reality dance experience where the headset becomes the audience’s tool to reacquaint themselves with the human instinct of embrace. On the other hand, Dealing with Absence offers the audience a glimpse into a private, intimate journey executed by performers wearing VR headsets, and dancing movements inspired by films (such as Tarkovsky’s Mirror or Bergman’s Persona) exploring the theme of absence through gestures . The audience can witness this journey from afar, behind their online screens, while maintaining a clear awareness that this framework is absent for the performers, who are immersed in the virtual reality headset throughout.

The connected audience streams the dancers choosing physical spaces to “set” their theme of absence, experiencing the tension between the perception of the place shown in the headset and the one they are in. Absence as a new presence: the VR device constantly calls us back, as noted by Antonio Pinotti and Francesco Casetti, to the sense of presentness, along with that of unframedness and immediateness. “Presentness,” the authors suggest, “should be understood in a double sense: of the user feeling present in the environment (a condition frequently referred to through the formula ‘being there’), and of the digital objects perceived as actually present in the space-time of the user.”

Together with Agnese Lanza, Margherita Landi seems to attribute a dual value to the VR device: it embodies the concept of absence both as being elsewhere, not belonging to anything, and simultaneously also as a place of presence in its concealed condition. Desire and lack—presence feeds on absence, while disappearance generates a perspective reversal. “The hidden is the other face of a presence” wrote Jean Starobinski, “like seduction and fascination, which are the forces that later lead to desire, to nourish oneself with what is hidden.” [1]

The artists work on absence, by transforming it into something that can be present again. The paradox or contradiction in the nature of the medium arises when the desire for presence emerges from a technologically mediated form of communication, represented by the VR headset. Hito Steyerl questions this, formulating the concept of the “economy of presence” in the essay The Panic of Total Dasein: Economies of Presence in the Art World:

“Why is presence so coveted? Because it conjures the promise of unmediated communication, the splendor of uninhibited existence, an experience that appears unalienated, and an authentic encounter between human beings” and “The claim for total presence does not oppose the use of technology; it is rather a consequence of it.”

It is worth relating Landi’s reflection in regards to anthropology, a field of study dear to her, which she started from. According to scholar and anthropologist Ernesto De Martino, [2] absence stems from a ‘crisis of presence” caused by external events for which we are not responsible. It leads to total disorientation, generalized uncertainty, and a crisis of identity, both individual and collective. [3] Available online for the spectator, the title of the work, Dealing with Absence, induces an error: dealing with absence—symbolized through virtual technologies, the lack of spatial and geographical connotations, the absence of self-recognition, and communal isolation—naturally leads to a necessary exploratory and transformative phase that surpasses the distressing here and now.

In the virtual experience, the absence of reference points reflecting the historical human condition prompts the search for familiar, recognizable elements that can be linked to actual and emotional experiences. The redemption of humanity in a moment of significant loss of centrality, and identity concealment, is regained by recognizing a sense of belonging to the community and its certification, by sharing places of one’s memory and, in the case of Peaceful Places, through the gesture of embrace. This gesture validates the essence of being there, strongly countering the extreme peril of losing oneself in annihilation.

Therefore, Peaceful Places implies the necessary inclusion of the spectator in an active relational dynamic. The virtual experience, mediated by images of bodies and architectures, empathetically induces a transcending of thresholds as a genuine technique of escape and metamorphosis to reclaim presence.

A Virtual Cube for Real Dancers

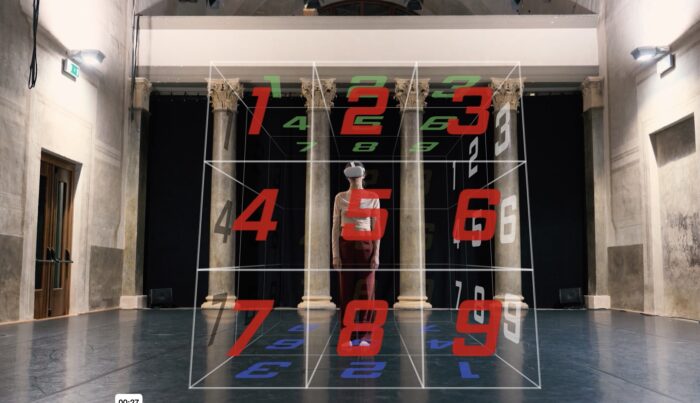

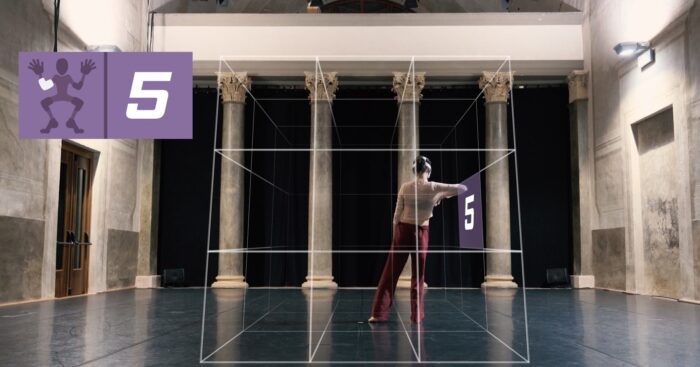

Through a series of residencies in Italy and abroad, Landi advances the concept of defining a virtual space as a training ground for dancers wearing the headset to create impromptu choreographies. Guided by visual cues displayed in the headset, the dancers can understand how to progress, which part of the body to move, and where to place it. The initial prototype, named Landi’s Cube, allows the direction of a single dancer using a controller. Margherita Landi introduced it in June 2022, on the occasion of Cinedans, at the VRLab, in Amsterdam.

The second phase occurred in December 2022, at the Creator’s Lab of the Immersive Tech Week organized by VRDays and Eindhoven Design Academy. In this instance, two dancers are directed by Landi not with a controller but from a keyboard, allowing for more compositional precision and speed. In Milan, thanks to practical and theoretical-philosophical elaboration, Landi secured a residency grant at An Icon (affiliated with the University of Milan) and simplified some technical details from March to July 2023 to work on the theme of the first performance to be developed with the Landi’s Cube.

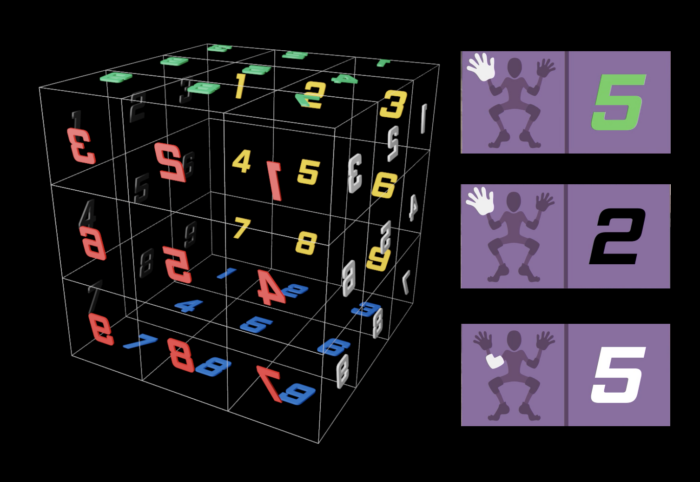

The Landi’s Cube is a spatial visualization system that enables real-time learning of movements. It originated from the amalgamation of various influences: Laban’s cube, the game Twister, and the Rubik’s cube. The application leverages the pass-through mode of the Quest application, enabling the visualization of the real space through the headset and the addition of augmented reality information.

This allows you to see your entire body and potentially other dancers and interact without avatars. The system is inspired by Laban’s cube, as it presents itself as a cube within which the dancer is positioned, becoming a guidance system. Through the headset, a thin grid is displayed, indicating numbers from 1 to 9 on each side of the cube. Each side has numbers of different colors, similar to the Rubik’s Cube. The system combines a body part (hand, elbow, foot, knee, head) with a colored number, identifying a specific spatial area to place the body part. By varying the speed at which these combinations are provided and adjusting the size of the cube, it is possible to construct a choreographic dynamic. Two dancers can be directed using two Bluetooth keyboards, each connected to a VR headset. Through them, Margherita Landi proposes a choreographic track she has constructed or random instructions generated by the program. By combining different “cues” (visual indications and dimensions), Landi can build a short improvisation.

In October 2023, the artist presented the first study titled TREMENDA PRESENZA, that makes use of the Land’s Cube. These occasions are crucial for publicly presenting segments of her research, engaging in exchanges with industry professionals, and experimenting with various technical solutions, unexpectedly accelerating the process.

As part of the performance titled TREMENDA PRESENZA, the Landi’s Cube was showcased in Milan at the Spazio Ariella Vidach AiEP at the Fabbrica del Vapore, marking the first outcome of the An Icon Residency. It was presented as a workshop, titled IN BETWEEN, at the Interactions Festival in Rome on November 8th. At On Live in Turin on November 26th, the Landi’s Cube was introduced as a talk accompanied by a brief improvisation performance with Amina Amici as a local dancer. In less than an hour, Amici grasped the language of the Landi’s Cube to collaborate with Landi. Subsequently, the audience was given the opportunity to try the system.

Anna Maria Monteverdi: In both projects, Dealing with Absence and Peaceful Places, absence is the main theme. The absence of physical contact, the absence of the body, the absence we have experienced during the pandemic.I’ve experienced Peaceful Places with your guidance at the PIM space in Milan, and recently in Turin, in the courtyard of the Rectorate during the European Days of Theatre and Technology. When the audience removes their headset, there’s a felt need to seek a real body, to search for genuine physical contact. Was this the purpose of the project for you?

Margherita Landi: Yes, a virtual experience that triggers a desire for the real.In Peaceful Places, the attempt to engage with virtual bodies, that feel very close but are lacking substance, leads the audience to embrace both emptiness and dance. Inside the headset, one experiences closeness; outside the headset, there is absence.

In Dealing with Absence, the online spectator never sees what appears to the dancers through the headsets. Something happens within the performers, the body is touched by something else, and movement is generated. It’s a solitary journey: there is no shared physical space, rooms and places remain separate, with no contact between bodies living in the same moment, in a diffracted elsewhere, sharing the same experience. It seemed like a possibility for connection, a hope to overcome isolation, and that’s when I proposed to Agnese Lanza to envision a community of dancers scattered across Italy but connected through gesture, as it happens in Dealing with Absence.

It appears evident to me that rather than a sociological reflection on the virtual device, you are aiming for a consideration of the tool as both a generator and dissipator of absence—a transformative vehicle, in essence. This approach aligns more closely with an anthropological perspective.

It is a common (Western) habit to conceive absence and presence as antithetical when, in reality, the relationship between these two states involves interpenetration at different levels. In our culture, we tend to avoid absence, associating it with emptiness and death, as Derrida elucidates in his “metaphysics of presence.”.

We are in a feverish search for new ways to be present, ubiquitous, immortal, and it seems evident that Virtual Reality (VR) is one of these avenues towards ubiquity. However, VR possesses a unique characteristic that makes individuals present in a virtual world while simultaneously present/absent in the real world. The body is physically present but engaged elsewhere, existing both here and elsewhere—a concept that has always fascinated me, representing significant creative and perceptual potential, especially when one has the courage to remain on the threshold.

In Dealing with Absence, the dancers intentionally navigate between these two realities. Their gaze follows the video track, while their bodies attempt to reposition it within the surrounding space, activating their physical and emotional memories related to these chosen intimate spaces. The system also activates a tactile sensitivity akin to the experience of dancing blindfolded, providing a way to reconnect with one’s body, engaging senses not involved in visual perception and relocating them in real space—an integration and presence practice.

I found it intriguing to conceive absence as the “inability to see.” I was immediately fascinated by the fact that observers cannot see what VR users see—the absence of the image from which movement originates. This differs from interactions with smartphones, which lack the same potential to generate body movement and interaction with the image. Typically, a person absorbed in their smartphone is almost immobile and relatively unexpressive; usually, only the thumb moves. This state doesn’t allow observers to understand what the person is experiencing. In contrast, with a Virtual Reality headset, movement is almost inevitable, even just to explore the content around oneself. Something imprints on the body, enabling a form of empathy from observers. Through the user’s movement, one can comprehend the experience and emotions the person is undergoing within the VR headset.

There is a reflection on the materiality of absence…

Yes. There’s a tendency to perceive absence as immaterial, forgetting that to be perceived, it requires access to one’s physical and emotional memories. In both projects, I don’t believe that the video generates the emotional state; rather, it’s the movement, activated by a visual stimulus and enforced through mimesis, compelling the projection of the video image onto the body. This triggers a mechanism of evoking physical and emotional memories. This is particularly evident in Peaceful Places, for instance, where the choice of which pair to mimic is guided by the emotional quality of the gesture. I am drawn to it because I know it and miss it, so I retrace it, and in retracing, relive it.

Movement, therefore, represents a further immersion into the immersive content.

An absence can generate a more acute presence (quoting L. Crozzoli Aite). It seemed very clear to us that this occurred in the choreographic process activated in both Dealing and Peaceful. We then pondered how technology could “deal with absence,” giving rise to a trilogy of projects with Agnese Lanza—a process of approaching Absence. Thus, in Dealing with Absence, we delved into absence as distance, in Touching Absence, absence as a relationship, and in Embodying Absence, absence as an inner state in relation to memory. In all three projects, the headset always serves as a threshold to another realm, leaving the body in a state of simultaneous presence and absence.

It seemed logical to open a new chapter with a performance titled TREMENDA PRESENZA, where we explore the presence of the invisible—a development of the work carried out on absence. This also marks the initial outcome of the interactive project Landi’s Cube, in 6DOF (Degrees Of Freedom).

Where does the need for the Cube originate? Is it from your experience as a dance instructor, your intention to advance VR performance formats, and your understanding of creative-choreographic processes based on Laban’s? How did the idea of constructing choreography in real-time come about?

These two questions are intertwined for me; I cannot separate them. The concept of the Landi’s Cube arises from the necessity of creative spontaneity that brings the gesture as close as possible to authenticity, which is the aspect I most seek in my work. I stumbled upon technology in 2012, starting with cell phone videos to capture unique and authentic moments, eventually leading to Virtual Reality that, for now, has taken the form of a cube, but it could change.

The need for spontaneity and authenticity stems from my background as a dancer. Coming from classical dance, I was trained in a strict and predefined language. Transitioning to contemporary dance, I had to and wanted to break down that language, immediately being captivated by improvisation, which allowed me to discover the language through which my body could and wanted to express itself. I was particularly fascinated by the concept of instant composition, a specific area of improvisation.

For years, I worked with improvisation and on degrees of freedom in relation to listening to others, on the theme of limits as creative potential, on concepts of perception and attention, and on how to maintain the authenticity that occurs in improvisation even in choreography. At some point, I started asking the opposite question: how to place the dancer in specific conditions where they are compelled to be authentic, where the gesture is obligatorily dry and concrete, simultaneously retaining all its vulnerability and humanity, and not acted in an artificial or decorative manner. On these shared premises, the collaboration with Agnese Lanza began, who, like me, was in search of the same essentiality and creative precariousness in movement. The word “precariousness” united us in a common research intent because perhaps there is nothing more human, spontaneous, and authentic than the precariousness of life, the world, the body, and thus, the gesture.

With Agnese Lanza, we experimented with real-time choreography learning mechanisms through videos, smartphones, and eventually, Virtual Reality headsets. Learning in real-time immerses the body in a movement that is inherently precarious, in search of a present that constantly eludes, chasing a gesture that continuously evolves, its endpoint unknown, demanding an expanded, dynamic, and active attention and listening.

So, it seemed logical to continue. I wanted a mutual spontaneity that would challenge not only the dancer’s role but also my own. In this project, the role in crisis (I always speak in terms of crisis/opportunity) is that of the choreographer, who doesn’t exhaust their role in rehearsals but finds themselves on stage with their dancers in a new capacity. Thus, I questioned how a system could work, allowing me to work with local dancers, which is something I am experimenting with in search of new production systems that leverage the concepts of spontaneity and community as their strength. My dream would be to have a community rather than a company of performers. So, I got to work, and the cube’s form was a simple resonance with the process I was already conducting with choreographic traces in 360-degree videos, which eventually evolved into a 360-degree cube.

Is it important for the user to use this device beforehand?

For amateurs, a few minutes are sufficient to grasp the system. For dancers, and to construct a performance, it is crucial to have a basic understanding of navigating within the cube. To reach a performance level, slightly more than a day of rehearsals is necessary. This is mainly because it is essential for me to learn the expressive language of the dancer in order to guide them effectively.

Is there a risk of uncreative repetition by the user/dancer? Perhaps a sort of “instruction manual,” depriving them of their expressiveness?

This is a question many ask, perhaps because they perceive Landi’s Cube as the artwork itself, and to some extent, it is. However, primarily, it is an instrument that can give life to infinite performances. Until used, it remains an empty box, similar to a guitar or piano containing a language of signs, the musical notes, which can create melodies, but nothing happens until it is played. The difference, though, is that it is a three-handed instrument, played in part by me (the choreographer), the dancer, and the apparatus, which can be invoked with random indications. The Landi’s Cube, facilitating direct, non-verbal communication between the dancer and choreographer, can fall into monotony if not “played well,” if there is no attentive listening, much like a poorly played guitar making the melody less enjoyable.

Depending on the project, it might be more or less suitable for the dancer to know the score. Presently, I enjoy surprising dancers with unexpected indications to elicit genuine reactions on stage. For example, the first project realized with the Landi’s Cube, TREMENDA PRESENZA, works best when the dancers are less familiar with the score. They tend to interpret it, losing some naturalness, which aligns with my choice to remain in spontaneity.

Dancers often feel liberated from the burden of thinking, enjoying this instrument with a nature akin to a video game that lightens the creative process, removing the seriousness that can sometimes be imposed. Despite this, they face interesting challenges: listening, allowing themselves to be guided, choosing how to interpret indications, immersing in a see/not see dynamic that compels them to remain physically present, and deciding when to embrace the freedom to interrupt or change direction. It’s a system of improvisation, not coercive to the dancer, who can execute the same indications in infinite ways, and each dancer might perform the same sequence differently.

Your previous work originated from the need for emotional empathy, sharing a gesture that brings people closer, like a hug, which, even in the virtual environment, evokes a special feeling for those who experience it. What kind of emotion did you want to evoke in the audience this time?

Landi’s Cube is merely a system containing a language of signs; if not applied to a message, it doesn’t produce meaning, much like the alphabet itself lacks inherent meaning but can be used to write poetry, varying in quality. This is why I wanted to develop a preliminary work with a clear message. In TREMENDA PRESENZA, I delved into the invisible and Rilke’s angel of elegies. “The angel of Elegies is the being who guarantees the recognition of a higher rank of reality in the invisible,” wrote Rilke in a letter to Witold von Hulewicz on November 13, 1925.

In this sense, speaking about a higher rank of reality, not in Virtual Reality but in what the audience imagines and projects onto a Virtual Reality that is felt fitting. Often, it has been pointed out that it’s frustrating not to know what the dancer is seeing. I aimed to demonstrate that it’s not crucial; what matters is what the spectator believes the performer is observing. For me, this is the fundamental difference between VR experiences (as the market presents them) and performance. In VR experiences, you want to look into the headset; in performance, the headset becomes a scenic mask like any other, and it’s up to the performer to make you believe in that mask.

How did the cube originate from a technical standpoint?

In the project Dealing with Absence, developed for Residenze Digitali, I had reached a visual synthesis of a cube, on each side of which I placed the video track of the choreography (in that case, scenes from a film). This allowed the dancer to follow the score regardless of their head and gaze’s position. I’m attaching an image to clarify the concept. One day, looking at this cube, I thought it could become similar to Laban’s cube. I studied at the Laban in London for a year, so I have some Laban training. However, I always found Labanotation language complex and challenging to incorporate, especially because learning a choreography from a sheet requires a time of interpretation and a second time of action with the body. I wanted everything to happen in a single moment. For now, it’s a cube because it’s the simplest thing to design and visualize, but even in this version, it changes shape and size. I hope to soon figure out how to adapt the system to a sphere or other geometric shapes.

How does your presence on stage influence the understanding and alter the motivation of the dancers? What does it change in the magic circle of the stage?

It has a significant influence; I am experimenting with finding the best position. During improvisations with the Landi’s Cube, I felt the need to be close to the performers to connect with them. In TREMENDA PRESENZA, on the other hand, I felt the need to follow the frame from the front, on the ground in a corner, at the edge of the audience. This position allows me, after a while, to disappear while remaining on stage and to have a frontal view of the piece. As the next developmental step, I am studying the possibility of guiding with a touchscreen interface. This would enable me to view all the performers’ cubes on multiple screens.

The professional relationship with Agnese Lanza: what are your areas of interest, and how do you collaborate?

We have very clear and well-separated areas of interest, with choreography being the common ground based on a shared taste. When we first met, Agnese’s research focus was on mimesis from a screen, while mine was on the choreographic, performative, and perceptual potential of VR. In the realm of the body, Agnese explores focus and attention, while mine centers around perception, emotion, ritual, and the digital. Since our encounter, these two research lines have merged, giving rise to a collaborative process that incorporates mimesis to move with the VR headset. We have co-signed several projects, and it’s likely that we will co-sign more in the future. Over the years, I have independently developed all the VR content for our works, delving into the technical aspects as well. The Landi’s Cube, not involving mimesis, was developed independently by me because it did not fall within our common interests. It underwent about a year of theoretical and technical development. Agnese, however, collaborated as a dancer and choreographic assistant during the creation phase of TREMENDA PRESENZA because she was interested in participating in this less technical and more artistic phase.

We operate as a flexible, fluid duo, composed of two independent artists. While we share a strong connection in our research and common interests, there is significant respect and support between us. Both of us pursue independent projects in parallel, a richness to bring to the Landi-Lanza duo.

[1] “Il nascosto è l’altra faccia di una presenza come la seduzione e la fascinazione, che sono le spinte che portano in un secondo momento a desiderare, a nutrirsi di ciò che è nascosto” J. Starobinski, Il velo di Poppea, in L’occhio vivente, Einaudi, Torino, 1975. Translated from Italian by the author.

[2] “Ernesto De Martino (1908-1965) delved into the study of presence, its crisis, the definition of disorientation, the dynamics and rituals of magic, and the risks to which presence is exposed, particularly in the context of death. Presence is a state that materializes in existing at a specific historical moment, within a particular existential condition shaped by memory and experience. It is closely tied to what he termed the crisis of presence, signifying a state of disorientation resulting from unforeseen and often painful events such as death, conflict, or migration. The trauma leads to a loss that extends beyond the objective and real, encompassing profound and symbolic aspects of one’s existence—geographical, historical, cultural, and personal. De Martino points to the risk of a separation from a state of domesticity: the peril of facing a crisis of non-existence.” E. Solito, Intorno alla crisi della presenza di Ernesto De Martino. Translated from Italian by the author. https://formeuniche.org/ consultato il 11 Febbraio 2022

[3] “To be in history means to give formal horizon to suffering, to objectify it in a particular form of cultural coherence, and to transcend it into a particular value: this simultaneously defines presence as the fundamental ethos of man and the loss of presence as the radical risk to which man – and only man – is exposed.” E. De Martino, Sud e Magia, Feltrinelli, Milano 1959, p. 15. Translated from Italian by the author.

Concept, Artistic Direction, Movement Research

Margherita Landi

XR Programmers

Fabrizio Ciolino, Sergi van Ravenswaay, Esther de Bruijn

Design

Matunda Groenendijk, Charlène Dosso

Production

ERC ADVANCED “AN-ICON. An-Iconology: History, Theory, and Practices of Environmental Images

With the support of

VRDays, Eindhoven Design Academy, Cinedans