Between Land and Sea

A review of the exhibition “Parthenope, Lighea and Other Stories”

On the occasion of the centenary of the Università degli Studi di Napoli Parthenope, Galleria Fonti curated the collective exhibition Parthenope, Lighea ed altre storie… to underline the commitment of the atheneum within the study and valorization of the sea, as central resource of the territory in terms of knowledge, culture and development.

“From the most remote times the elementary opposition between land and sea has been observed.” This opposition, in turn, has always been connected to a polarity of opposites: Catholics vs Protestants, conquerors vs settlers, friends vs foes. Accordingly, the sea has always symbolically represented the element of adventure, travel and exchange, while the solid ground coincided with firmness and rootedness.

Curated by Galleria Fonti and opened last October 2021 at Villa Doria d’Angri in Naples, the exhibition Parthenope, Lighea and Other Stories sets as its main motive the thin line that separates the land from sea. This line is the panorama outside the Villa’s windows—facing the stunning gulf of Naples dominated by the Vesuvius—and the pivot the whole show revolves around. Featuring works of six artists from across the Mediterranean, the exhibition celebrates the Parthenope University’s 100th anniversary and is an invitation to explore the sea as a political, poetic, and mythological subject in continuous transformation.

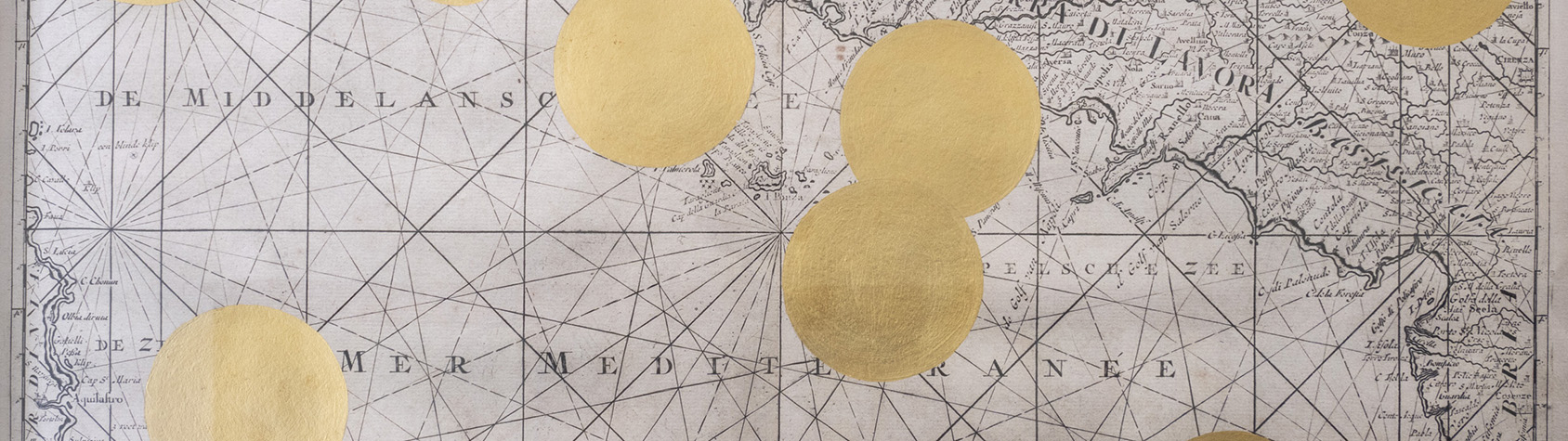

A line between land and sea might be traced at the core of Giulia Piscitelli’s (Naples, 1965) works. The artist intervened on the digital reproduction of two maps from the university’s Bourbon Archive overdrawing the silhouettes of the halos placed on top of the figures of Giotto’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ.

Employing the original oeuvre’s gold leaf technique, Piscitelli’s golden circles situate across the geographical map of the Mediterranean evoking an ideal threshold between the material and the spiritual, resonating with the artistic object’s inherent political consistency. By means of circumscribing and canceling some points on the maps, the idea of the line as a border is evoked, and its abstract, if not religious, meaning emphasized. Tackling concerns on cultural and national identity, these works might bring to the fore the most actual face of the sea—and the Mediterranean in particular: a political entity able to separate and diversificate.

In the works on show by Renato Leotta (Turin, 1982), the division between the land and sea is instead drawn through the grainy line of salt traced by the sea water. To realize Multiverso and Mare Chiaro, the artist indeed immersed the fabrics in the sea, leaving them to dry naturally to the rays of the sun. The horizon drawn on these nature-made canvases, like the underwater snapshot of the Plankton’s bioluminescence impressed by the moonlight, touch upon the concept of the median line theorized by Franco Cassano.

They narrate the inverted epic of the artist, born in Turin and returned to his parents’ native town in Sicily, seeking an alternative route to the trajectory of modernity. Here, the divide might be the one that historically has separated the industrialized North from the South, history from myth—as the sculpture Lighea suggests. A double temporality discloses: the narrative of the myth, which is timeless, and the teleology of progress. The difficulty of narrating the history of a nation lies in this duplicity.

The following sala presents a series of paper cuts by the German artist Christian Flamm (Germany, 1974). These works resonate with the adjacent Wagner Hall, dedicated to the composer who spent some time here writing the Parsifal. Three diptychs allude to a musical imagery: a portrait of a figure with a lyre, or a ballerina caught in the act of dancing, appear among the other scenes. Here, a solemnly bichromatic sonority dominates the collages, all realized by hand by the artist, together with a small and precious ink drawing of a harp. Flamm’s work evokes another facet of the sea, richly investigated by scholars, that is that of exchanges.

This time, the separation between the land and sea is traversed by cultural contamination, of which music or dance rituals constitute an important part of timeless memory. As an expression of resistance and continuity inscribed in the texture of the sea, music acted for centuries as a melancholic bridge between far places. After all, the sea that washes Naples’ shores attracted artists, musicians, dancers and composers, from Nureyev in Li Galli to Wagner in Villa Doria. The sea can be read as an “ecology of rhythms, beats, and tonalities that generate sound cartographies in which unprecedented sounds and feelings cross, contaminate, and creolize the landscape.” A new geographical space where “sound cartographies cause an interruption, or a cut, in existing cartographies.” A line is traced again, but immediately blurred.

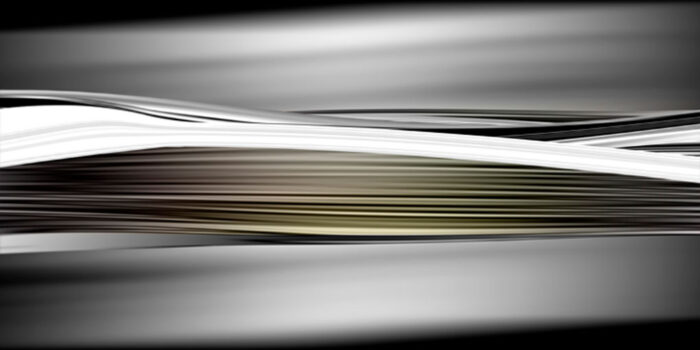

The same harmony of the Mediterranean landscape is the source of Paul Thorel and Marieta Chirulescu’s seascapes, which explore vision using different media. Chirulescu’s works appear to be “less about technology per se than its residual effects on (and capacity to describe) memory, personhood, statehood, and canvas.” Thorel, to whom Partenope, Lighea and other stories is dedicated, in turn manipulates the image by combining photography with digital treatment, to the point where it becomes almost impossible to recognize the original. In the two artists’ works, any attempt to draw a line is blown. In Chirulescu’s interchangeable sky and land, one may take the place of the other depending on how we read her work. Realized on the occasion of a residency at Villa Massimo in Rome, these landscapes play with vision and illusion, as overturn-able perspectives.

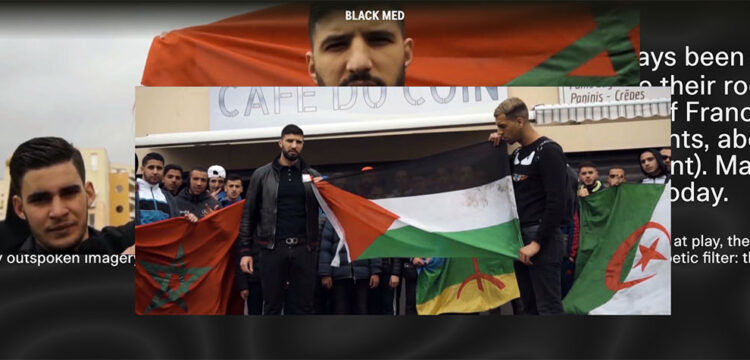

If the Mediterranean is “the sea amid the lands”, and if there is no Mediterranean without the land, then the Mediterranean doesn’t exist without Africa. Nor would Europe, notwithstanding the borders traced by its “fortress” and their inaccessibility, built at the expense of Africa itself, as Fanon argued. To address the sea today is to primarily address it as a frontier and boundary—conversely to what Carl Schmitt assessed. To investigate it, means interrogating history, identity, and memory, beside landscape.

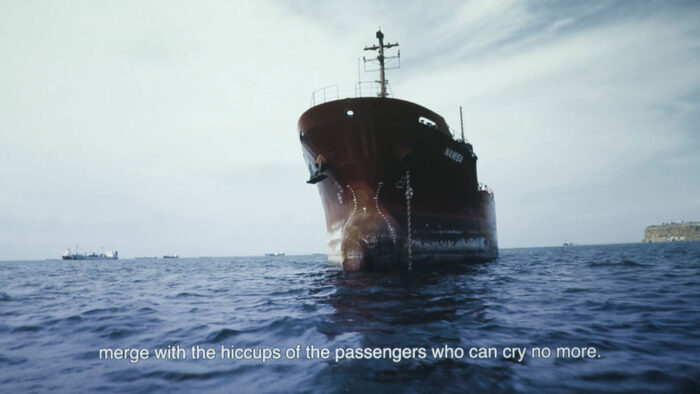

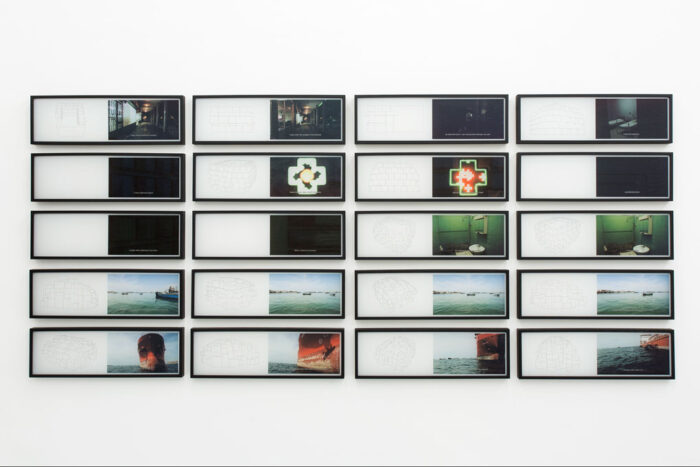

This is what the video installation by Kiluanji Kia Henda at the second floor of Villa Doria does. Here, Concrete Affection – Zopo Lady, complemented by a series of seventy-five still frames and related ink drawings, seventy-five, account for the last few days of the Portuguese occupation in Angola. Hometown of the artist, it conquered independence only in 1975, after gruesome turmoil and a civil war.

Inspired by Ryszard Kapuscinski’s book, Kia Henda’s video narrates the last hours of the Portuguese occupation registering the suspended void that poignantly describes the status of modern diasporas. Over twisting the plot, the leaving of the colonizers for a moment stages the universal, liminal condition of migrants, evoking its excruciating feeling of the unknown, well opposed to the “unknown” of the sea above the Herculean Columns.

It is not easy at all to talk about the sea and the Mediterranean without risking to fall into stereotypes. Conceiving an exhibition on the sea, means to mobilize landscape, as well as history and modernity. The Parthenope University, formerly the Naval Institute, is also not at all a natural place where to carry such a task. As Paul Gilroy asserted, ships are the political entity that conveyed modernity, and a mobile laboratory for the plantation system.

Listening and seeing what the view of the sea may tell us is internalizing what Gramsci defined “an infinity of traces welcomed without the benefit of the inventory”, while learning to break the idea of wholeness, that might instigate to reflect against the “unthinking assumption that cultures always flow into predictable patterns, congruent with the borders of essentially homogeneous nation states.” And learning to read the story from the other side of the sea, as well as the interstitial histories written between land and sea.