Archive of Dispersal

A space to reimagine what it means to create, disseminate, dismantle and continue the life of an archive

The new book by Tara Fatehi Irani, Mishandled Archive, records and reflects on her intentional scattering and displacement of a family archive. The book offers a space to reimagine what it means to create, disseminate, dismantle and continue the life of an archive.

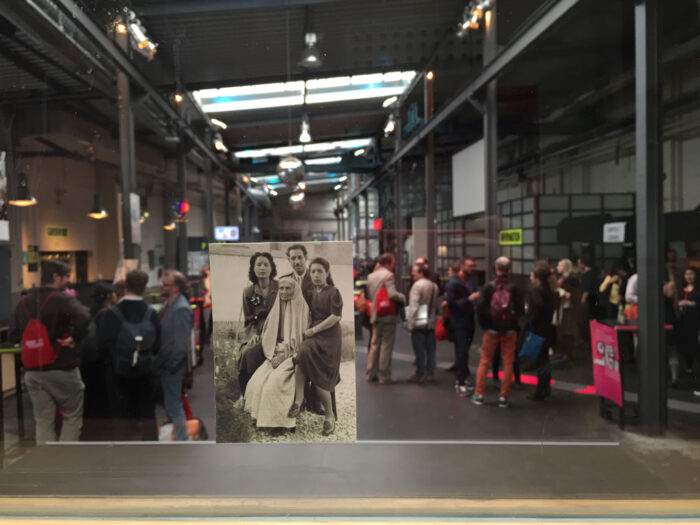

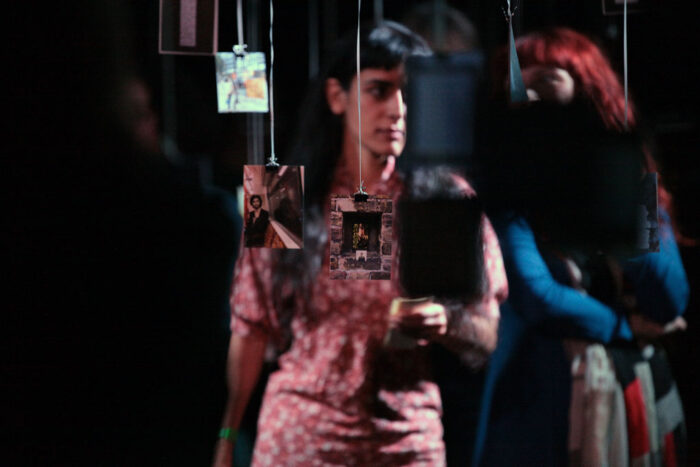

Every day for a year, Tara Fatehi Irani dispersed fragments of family photographs and documents in public places in the UK, Iran, Switzerland, Kurdistan, Germany, Italy, Ukraine, the Persian Gulf, and in between borders and amongst the clouds. She made a photograph, an annotation, a dance and an Instagram post on the site of each dispersal.

The project embraces nomadism, taking up temporary homes in unexpected public places and in the bodies of those who encounter it. In this nomadic dispersal, there is potential for sites, bodies and histories to intermingle and reimagine themselves through a fantasy of possible futures.

Contributions by artists, writers and researchers expand and reflect on the themes of the project including creative engagement with archives, anthropophagy and history, accumulating forgettable objects, fictional kinship, homelessness, and choreographing uncertainty.

The publication is designed by David Caines and features contributions by Nicola Conibere, Maddy Costa, Diana Damian Martin, Eirini Kartsaki, Joe Kelleher, Shahram Khosravi, Giulia Palladini, Mary Paterson, Marco Pustianaz, Anahid Ravanpoor, Holly Revell and Jemima Yong. The following is a short review by Giulia Crispiani and an excerpt of the book, Marco Pustianaz’s Lives of the archive (A stranger’s edit).

What is contained in other people’s memories, in those images that fix moments? How do they become so attractive when we lose track of their provenience, as they gain new consistency when their background changes, when we displace them. What do they bring with them, beside the eyes of the portrayed? Do they ever get to see or to imagine their new surroundings?

First of all, Mishandled Archive is a daily commitment, a routine and a ritual. The hand of the mishandler is careful to keep the score, whilst adapting the celebration to each instance, all for them to find a new home. The future is only imagined, and deeply intertwined with the past—the vector is shifted. The mishandler always returns to a past, but never nostalgically, because she invests every day to leave notes for those to come. Those notes are rather records than prescriptive instructions, yet how would you feel if you’d find such a trace? How would you treasure it? How would you continue its life?

The mishandler keeps herself busy to set memories in motion, to find a new landscape for a figure, to have them live beyond their histories and their bodies. Yet, she sets up both a dance and an archive—a desiring account, a hint, a rite for their future lives to stem rhizomatically from this one instant, as it’s offered a new backdrop, a new owner and a new box, this one image becomes a memory of others—of those who land in the archive, because the mishandler has faith in the founder. As for many artifacts, once they are shared they exist beyond their maker. Your words are passed to the witness. The same happens to images. An archive is always born to be witnessed. When the photo turns into a postcard, the dance remains textual. This allows me—who can’t really dance—to dance along. The mishandler knows that recording the temperature can remind me of my skin—or help me imagine what it felt like to the hand to pick up a photograph, it makes me desire to have this chance.

The mishandler does it for a year, and we get to follow her moves—both in the sense of travels and dances. Her invisible body is always behind us, and she wants us to look ahead and around us. She exists only as an archivist, she acts and files her actions into a book mishandling images, she makes new ones, she tries to keep track of their existence after she has left them. Before she has them returning to paper, the mishandler shares them online, reducing the delay of the dance. Some might have danced the same dance on the very same day, who knows. But when those memories return to paper they have changed substances, they’ve already turned into several dialogues. Each of them gives new suggestions for thinking the world, from the archive outwards, and vice versa, from the world inwards, to the archive indeed, but also back to the subject, who becomes aware of how tangible each of our memory is. To turn them into images inserted in different geographies is what creates landmarks, and how to connect those landmarks has already drawn a map of the world we inhabit. In this mishandled archive, both timeline and map are no more reliable tools than the body that moves through them.

Lives of the archive (A stranger’s edit)

Imagine a picture, a document, a certificate, partly straddling the boundary between private and public. Not just photographs, but also letters, ID cards, newspaper clippings, and so on. By being entrusted to the artist, they become part of a material collection, each item tangled up in stories—whether told, pieced together or imagined—as to who is pictured and where, as to the occasion behind the image or document. Each item may serve as a source for a micro-history founded on hearsay and guesswork. This step marks the beginning of a gathering together of disparate items into a single place, following a centripetal movement. Call this collection, say, “the archive”. Although it is debatable to what extent this can be called the artist’s own personal archive, through meticulous assemblage and accumulation it becomes for her like acquired family.1 At the same time, detached from its previous context, each item jostles for relevance in the new collection: forgetful of its past, it becomes a fragment of a story yet to be told.

Imagine this archive being displaced from Tehran, where it had mostly been gathered together—although the single items might point to a number of other locations—to London, subjected to a diaspora of its own, though also resonant with the diasporic experience of an Iranian artist settling in the UK. Having left her country, she now takes back with her, so to speak, the whole of Iran shaped as an archive of digital fragments. In London, for each of the items one copy is printed out. Through the medium of digitization, the archive mutates and spawns other instances, similar yet divergent, each with its own singular form and appearance. There are now three archival instances, two analogue, one digital: the earlier material collection (“the archive”), comprising different documentary genres, the digitized archive (an archive of files made of code), and the printed archive (the archive of copies). Printing homogenizes the original documents by turning them into visual objects, each print similar to a photograph, whether or not it was one to begin with. Although the three archives may look similar in content, they are liable to different destinies. The destiny of the third archive is what concerns us here. This print collection is a temporary archive made up of fugitive items, each ready to go its own separate way. The only reason the artist has reproduced them is to disperse and disseminate them, one at a time. Even though they still point back to the originals, their emergence counters the archival impulse towards centralization present in the first two instances with a different logic. While they have been produced through acts of collection and association, the printed copy scatters the archive with its potential of autonomy and dissociation. Taking leave of the temporary archive, they play out its centrifugal momentum.2

What could be the name for an archive of dispersal, one intended to be scattered rather than preserved? Here, the suggested name is “mishandled archive”. There is a wealth of meanings in this expression. A mishandled archive may be the name of an archive that fails to be handled with due care, or according to prescribed uses. There is a connotation of wrongness, even of abuse, hinting at an operation that exposes the archive to unwonted consequences. While handling involves some kind of cautious manipulation, mishandling conjures up the sight of items passing from one hand to another, not necessarily the right ones. Bona fide archives have strict rules as to who handles their items and how. Items are guarded and kept in a secure location. They are housed. Mishandling an archive, therefore, entails multiple serious dangers to its preservation and inspection. Arguably, a mishandled archive may well be the name of an archive that is no longer one, having failed the procedures set in place for the functioning of an archive as such, whose primary goal is the preservation of sources, of origins. In this case, against all good archival practice, danger has been actively courted, at least since the printing of copies, which has punctured any residual aura around the uniqueness of “the archive”. In contrast to an original, bound to its location, a copy is a moveable object. Having neither place nor memory of its own, it is always out of place. It can only hope in the future.

1. That even a “family” archive can be alienated rather than treated as autobiographical is one of the most interesting aspects of this archival performance.

2. The interest in centrifugal movement and its fictional potentiality is also made explicit in the collaborative project between Tara Fatehi Irani and the sound artist Pouya Ehsaei, called /gorizazmarkaz/ (“centrifugal” in Farsi).

Mishandled Archive is published by Live Art Development Agency supported by The National Lottery through Arts Council England. The book is available for purchase here.