Appeal to All Western Countries

Safe and Sound #3: Yaniya Mikhalina

Appeal to All Western Countries by Yaniya Mikhalina is a part of the program Safe and Sound, curated by the duo League of Tenders as part of the Nomadic Program 2024–2025 of Vleeshal Center for Contemporary Art (Middelburg, the Netherlands), and first published by Nero.

Safe and Sound draws on a performance by American artist Jana Haimson, held at Vleeshal almost 45 years ago, in December 1979. In this improvised piece, Haimson combined vocalization with experimental choreography. Haimson is among the western artists who explored and developed various genres of time-based art, often using scores as starting points for performative improvisation.

To reflect the concept of the score, as well as the production and transmission of knowledge in non-western cultures, League of Tenders invited three artists of different origins, living across Europe—Natalia Papaeva, Mukaddas Mijit and Yaniya Mikhalina—to create their scores and propose someone to perform them.

These scores are addressed to and inspired by their communities, offering a means to unite people across borders, within diasporas, and far from their homelands. Performing these scores—through their bodies, voices, and spoken words in their native languages—becomes an act of shaping their communities as visibly present, seen, and “sound.”

This series also includes projects by Natalia Papaeva and Mukaddas Mijit.

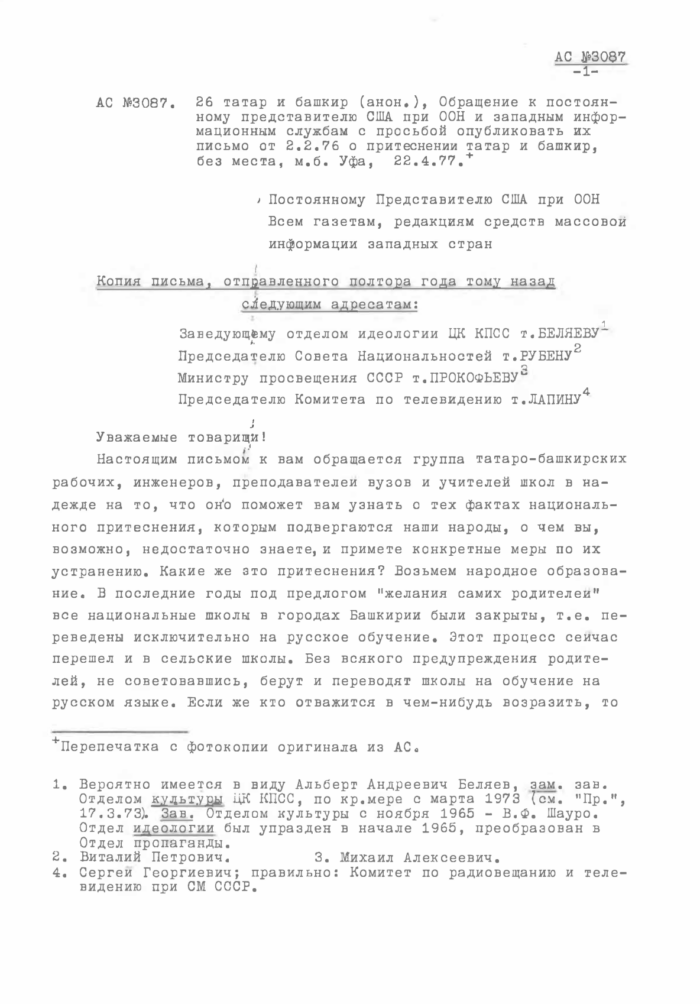

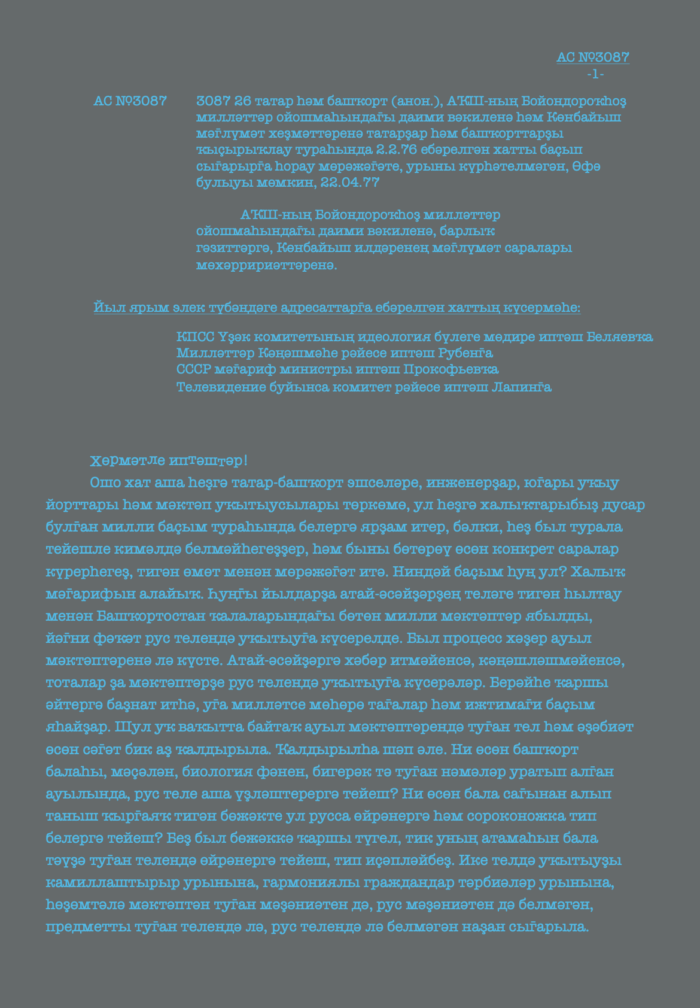

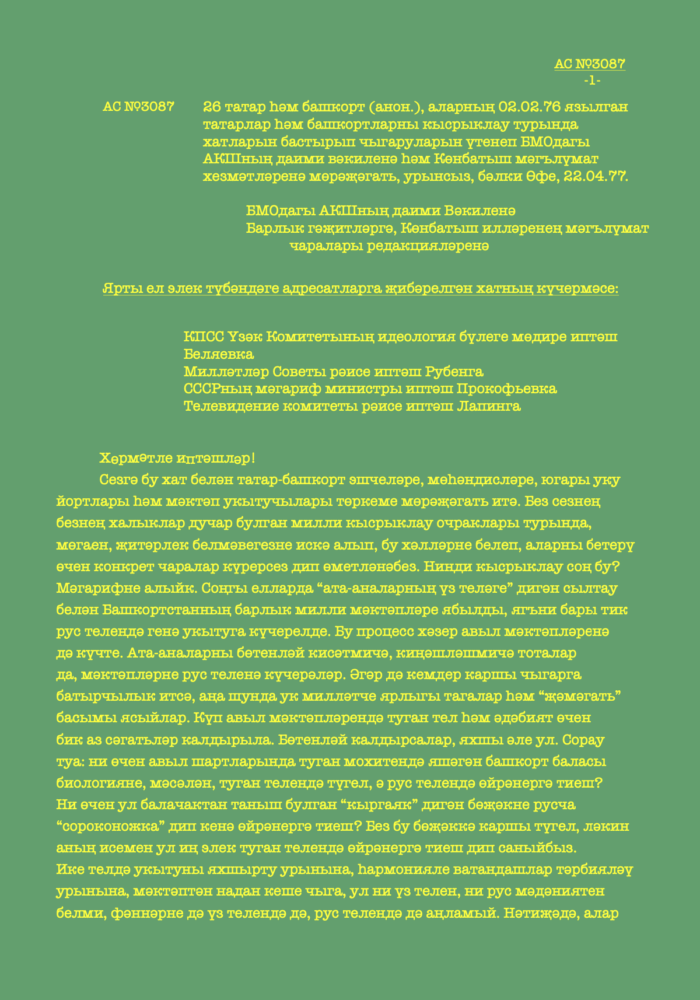

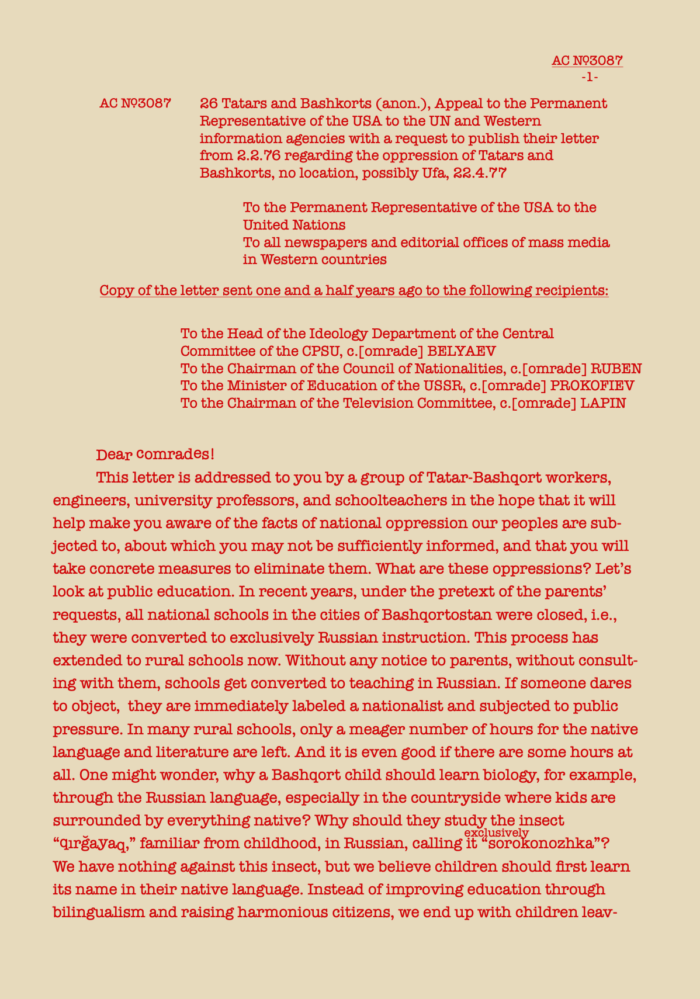

Appeal to All Western Countries

In 1977, a group of Tatar-Bashqort workers, teachers, and engineers appealed to all western countries through an anonymous letter sent to Radio Freedom, in a desperate gesture to draw attention to the colonial politics of the Soviet Union against the Indigenous languages and reforms in the educational system. This letter, written in a very emotional language, has never reached the international agenda and was silently stored in the Blinken archives in Budapest for almost 50 years, until I found it by pure chance earlier this year. Sadly, history repeats itself: the amount of people speaking Indigenous languages in the so-called russian federation is continuously decreasing. Reading the letter one gets a feeling it was written today, echoing the recent twists of colonial legislation.

This work is a deeply collaborative effort in carving out the collective presence, convened alongside people of four generations and many sensitivities. I have invited contemporary Tatar and Bashqort language activists to re-enact the original letter that has been translated from Russian to Tatar, Bashqort, and English. Mansur Möhammätshin, Zilya Biqtimerova, Ziliä Qansurá, Tansulpan Buraqaeva, Çiksezlek, Deenar, allapopp, Dinara Rasul(eva) generously shared their voices and exposed different positions within their mother tongue. A self-sufficient sonority of the native languages, a form of history in itself, is blended with an effort to imagine a Tatar-Bashqort soundscape.

The labor of contextualization stands as an important tool of recovering the past and opening a possibility of imagining a rooted future. Bashqort filmmaker Tansulpan Buraqaeva, in a spirit of Indigenous indifference to the compartmentalization of knowledge, has been both the translator, musician and one of the recorded voices in the project. The work is accompanied by a text of a Tatar researcher Leisan Garif that gives an insight into the history of colonial education politics on the Volga-Ural land. The humor, spiritual support and persistence of Masha Sarycheva, a co-curator of this project and a dear friend, made this community come true. Last but not least, the thoughtful sound design by sound artist Omar Itani took place in Lebanon, Beirut, thorn by continuous attacks by the Zionist entity. Necessarily translocal, this collaboration calls for urgent and simultaneous recognition of other than capitalist-colonial logics across the world.

Layering Indigenous instruments, archival and staged sounds, Appeal to All Western Countries is a heartfelt attempt to address the international community once again.

Credits:

A project by Yaniya Mikhalina

Sound design&mix – Omar Itani

Qurai – Ilyas Farhullin

Jaw harp – Tansulpan Buraqaeva

Song by Magfira Galeeva, Yarattim min rus egeten

Voices – Mansur Möhammätshin, Zilya Biqtimerova, Ziliä Qansurá, Tansulpan Buraqaeva, Çiksezlek, Deenar, allapopp, Dinara Rasul(eva)

Bashqort translation – Tansulpan Buraqaeva

Tatar and English translation – Çiksezlek

Text (un)heard languages by Leisan Garif

Thank you: Oksana Sarkisova & Blinken Archives Budapest

With kind support from OCA – Office for Contemporary Arts Norway

To read the text of the letter in Russian, in Bashqort, in Tatar and in English.

(un)heard languages

by Leisan Garif

Tel baylığı bay itәr, tel yuqlığı yuq itәr.1

Tatar proverb

My mother recalls how their education was switched to Russian after finishing primary school in the Tatar village in Bashqortostan. By 1974, only the Tatar language and literature classes remained in Tatar, while all other subjects transitioned to Russian. Students had to relearn all the terminology in Russian, and their grades in mathematics and other subjects immediately dropped. Teachers who were once addressed by their Tatar names—Fayagöl apa, Rәşit abıy—were russified to Rashit Lutfullovich and their ilk. These were the same village teachers, still speaking Tatar with their neighbors, but now forced to teach children in Russian. By the 1970s, such changes reached even the most remote schools. My mother’s sister, who was two years younger, studied entirely in Russian from the first grade onwards.

By then, Russian came to be seen as the “Soviet”2 language—the language of the state, institutions, economic progress, science, the army, and urban life. In the early years of the Soviet Union, ideas of national self-determination echoed both at the grassroots level among ethnic intellectuals and at the top in Lenin’s writings. However, by the 1930s, these voices had been consistently silenced—suppressed, distorted, or eliminated. While Tatarstan since 1920 and Bashqortostan since 1919 were recognized as autonomous republics, their autonomy in language policy steadily diminished. The Indigenous peoples of the western Urals and the eastern banks of the Volga (indigenous name Idel) and Kama Rivers – culturally and historically distinct from Russian-speaking settlers – faced increasing pressure. Before the revolution, Tatarstan and Bashqortostan had flourishing Muslim educational institutions combining religious and secular learning: madrassas in cities and mektebs in village mosques. Neighboring peoples like the Mari, Chuvash, and Udmurt—Indigenous Finno-Ugric and Turkic populations—had their languages and beliefs. None of them has been untouched by russification. Before rapid urbanization, caused by state-led migration and the Soviet project of “modernization” that justified the extractivist politics of the state imposed on Indigenous lands through the idea of progress, languages resided in the same places as their speakers. The “urban” status implied the general use of the Russian language: in cities, already in the 1950s and 1960s, children of Bashqorts who moved from villages often spoke little or none of their parents’ native language.3 In cultural narratives, Russian was portrayed as universal, while other languages were relegated to the provincial sphere.4 Indigenous languages were stigmatized as “backward”, and even though they continued to be spoken in cities, their use was increasingly confined to private circles. In public, native languages risked being dismissed as out of step with progress.

Khrushchev’s era introduced the vision of a unified Soviet people, not only politically but also linguistically—through the means of Russian. Officially, bilingualism was promoted, but the necessity of schools with mother-tongue instruction has been questioned. Some languages were deemed less viable or suitable for the “development.”5 In the post-war years, there were still schools offering education in native languages. For example, in the Mari ASSR during the 1948–1949 academic year, 56 secondary and middle schools were taught in Mari, and even five new ones opened. By the late 1950s, all Mari-spoken schools disappeared.6

The 1958–1959 education reform marked a turning point, making the study of Indigenous languages optional. Before the reform, native language education was guaranteed in primary and sometimes secondary schools. Afterward, there was pressure to switch to Russian from primary school. In some cases, the change was abrupt—like in all Karelian schools—while in others, like Chuvash schools, it was more gradual.7

By the early 1960s, only 47 languages were used in Soviet schools; by 1982, that number dwindled to 168. Final exams were conducted in Russian, as the language was needed for higher education. By 1961, only 6% of urban students in Tatarstan attended Tatar schools. Families stopped passing on their languages, perceiving them as losing value. In Ukrainian, this is described as “комплекс меншовартості”—“a complex of inferiority”, or a ”younger brother complex”, highlighting the dynamics of being subordinate to a dominant culture. The systemic displacement of Muslim education institutes in the Tatar and Bashqort context allowed Russian-language culture and institutions to dominate, asserting itself as the “elder brother.” By replacing Indigenous educational institutions tied to Central Asia and other Muslim territories, the Soviet state aimed to create a unified citizenry. To be a Soviet citizen meant speaking Russian and accepting its dominance in public life.

Who wrote the letter that we hear? Was it ever read? The document is a testament that even during this period of suppression in the Volga-Ural region, defenders of language did not remain silent. In the late 1980s, during a wave of national revival, a poem by Rәmi Ğaripov, “Tuğan Tel” (Native Language), gained recognition—long after the poet’s death. Written in 1957, a year before the education reform that undermined native language education, the poem reflects a deep reverence for linguistic heritage:

Şuğa la min belәm tel qәźeren:

Ber teldәn dә telem kәm tügel –

Köslö lә ul, bay źa, yağımlı la,

Kәm kürer tik unı kәm küñel!..9

Rәmi Ğaripov, “Tuğan Tel”

Ğaripov passed away 20 years later, in 1977. That same year, activists, frustrated by the lack of response to their letter about the violation of Bashqort and Tatar rights, sent it to western media. We don’t know the fate of these anonymous authors, but they may have been among the grassroots organizers in the late 1980s who led movements for linguistic and national rights in Tatarstan and Bashqortostan.

Echoes of this struggle persisted into the 2010s when linguistic conflicts in Russia’s ethnic republics were most visible in Tatarstan and Bashqortostan. Protests arose against federal language policies and the cancellation of native language classes. The 2018 amendments to the education law made Indigenous, or, to borrow the state’s vocabulary, so-called regional languages, including Tatar and Bashqort, optional once again. Previously, these languages were part of the regional curriculum, requiring residents to study them for several years, regardless of their origin. After the reform, they entered unequal competition with the “state-forming” Russian language. Resources for teaching native languages now depend on parents’ willingness and capacity to submit requests and fight for their rights.

Today, a period of silence has returned. The “Russian world” interests take precedence while dissenting voices are few, speaking quietly, anonymously, or only in safe, trusted spaces. Will these voices ever grow stronger and louder? Who will hear them?

1 “The richness of language brings prosperity, the lack of language leads to ruin.”

2 Wigglesworth-Baker, T. (2016). Language policy and post-Soviet identities in Tatarstan. Nationalities Papers, 44(1), 20-37.

3 Kiyekbayev M. J. (2004) Problems of the Bashqort population in modern conditions. Bashqorts of the City, p.15.

4 Faller, H. M. (2011). Nation, language, Islam: Tatarstan’s sovereignty movement. p.56.

5 Grenoble, L. A. (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p.57.

6 Alpatov V. M. (2000). 150 Languages and Politics 1917-2000. Sociolinguistic Problems of USSR und the Post-Soviet Space. p.103

7 Grenoble, L. A. (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p.57.

8 Kreindler, I. (1982). The changing status of Russian in the Soviet Union. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 1982(33). p.51, 54.

9 “That’s why I understand the worth of a language:

My language is not inferior to any other –

It is strong, rich, and melodious,

Only a poor soul would look down on it!”