Anti-colonial Fantasies

Ideologies and representation in the public space: a conversation with Daniela Ortiz

On September 29th and 30th, artist Daniela Ortiz presents a new performance entitled I Figli Non Sono Della Lupa, which will take place on the Gianicolo hill, in Rome, as part of Hidden Histories 2021 programme. The work is inspired by the equestrian statue of Anita Garibaldi, one of the few public female sculptures in the city. Commissioned in the fascist era by Mussolini, it shows the woman bare-breasted, holding a gun in one hand and her baby in the other, while riding a rearing horse. By opening a dialogue from this representation, Ortiz’s work generates a visual narrative in order to critically understand how childhood and motherhood are ideologically manipulated and controlled by yesterday and today’s fascist and colonial political systems.

Providing a glimpse into Ortiz’s parallel practices as an artist and militant, the following interview deepens the line of reasoning developed by the artist in the preparation of this performance and retraces the origins of her long-standing research on public monuments as tools to reinforce structural racism and patriarchal ideology.

Hidden Histories is a site-specific public program, consisting of performances, workshops, talks and urban explorations, meant to reflect on the cultural and historical heritage of Rome from a decolonial perspective. Conceived and curated by LOCALES, a curatorial platform founded in Rome by Sara Alberani and Valerio Del Baglivo, the project presents this year its second edition, running from June to October and including interventions by Stalker, bankleer, Josèfa Ntjam, Leone Contini, Daniela Ortiz and Adila Bennedjaï-Zou. As the program unfolds, a series of interviews conducted by Marta Federici with the artists of HH 2021 will explore their research and provide a broader context for each.

Marta Federici: I’d like to start from the fact that you are both an artist and a militant: how do these two spheres, art and militancy, interact in your experience? Can someone be a militant through their artistic practice or rather the two things trace two parallel paths?

Daniela Ortiz: Well, I think it’s absolutely necessary to make art about political or social issues—that is what I do myself. But militancy is another type of work that has nothing to do with exhibition-making. In militancy, you must attend assemblies, organize meetings, take decisions, and be political. Militancy always deals with collectivity, never with individual work. On the other side, artistic work can obviously reinforce the political work one is doing, by questioning certain issues. Artistic tools have been used, in different moments in the history of popular uprisings—but it is culture that has played a bigger role at times. Because culture is not one artist with one artwork, but rather many people working simultaneously to create an alternative imaginary or accompany a revolutionary process.

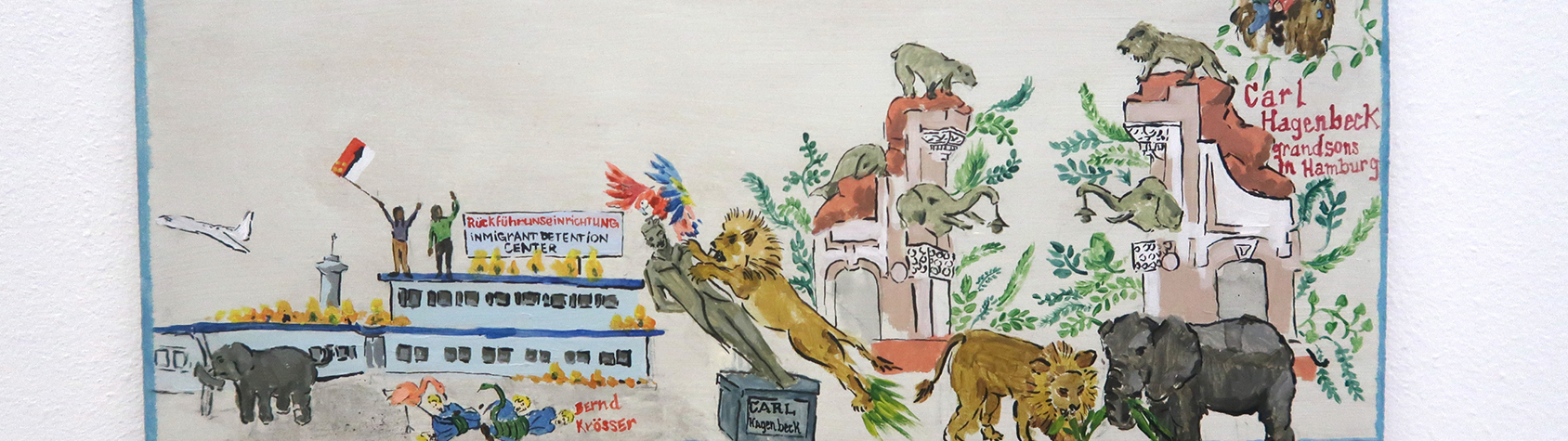

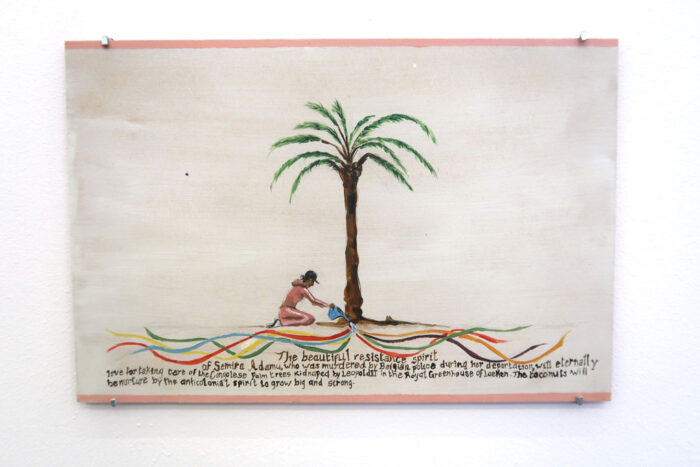

Part of your artistic practice focuses on creating visual narratives, through paintings, drawings, embroidering, and children’s books. As you said during a recent talk, these narratives generate “anti-colonial fantasies”, which is a beautiful expression. Etymologically, the word “fantasy” specifically refers to the ability and possibility of the human mind to create images, so I was wondering if you could tell me more about the role that images have in your work, about how they come alive. And also, what part do images play in anti-colonial and anti-racist resistance?

First of all, I want to clarify that “anti-colonial fantasies” is a quote from a publication by Imayna Caceres, Sunanda Mesquita, and Sophie Utikal, made a few years ago and which carries this very title. Coming to the question, I have studied painting, all the traditional techniques around this medium, and how to build an image: this is how I started. When I moved to Europe, I didn’t have enough time, money, nor physical space to do this kind of artistic work, so I began to use more conceptual, performative languages, which, on the one hand, have a more Eurocentric white esthetic, but are nevertheless cheaper and more accessible. These media allowed me for instance to present an intervention in the chocolate store where I used to work. But then two things happened. First, one day Brazilian artist and a friend Marissa Lôbo told me that the content of my work was not fully connected with that super white, European esthetic, but that it rather seemed to respond to a white cube contemporary-art-world vision. Second, not much later, I got pregnant, and spontaneously started to approach children’s books and to deal more and more with children’s materials. I started to read about the policies imposed on migrant family’s children raised by single mothers, while at the same time I was also researching racist and colonial statements found in children’s books. Actually, my return to images happened primarily through children’s literature. Meanwhile, I regained more time and opportunities to draw, paint, and do similar stuff, and I realized that I had forgotten how much I personally enjoy doing that. In the end, I decided to reconnect with the possibility of creating images myself. Images can be a territory of liberation where you can invent whatever you want. You can create an entire reality inside the painting you are doing, with its sizes, colors, names, everything. But when I speak of anti-colonial fantasy, I don’t refer to something unreal; in fact, in most cases, I refer to reality. Many of the works that I have been painting or drawing have to do with anti-colonial utopias rooted in reality. There are many territories in the global south, communities, towns, and peoples that have struggled and succeeded, and have been living liberated. For example, you can think of the Zapatistas; or some territories in Colombia, like the Cauca region; or the Mapuche people. Those contexts bear witness that a different existence is a real possibility, although power wants to destroy it: that is why they are persecuted.

Moreover, images are also important as a possibility of creating memory and oppose the manipulative pictures that are produced by the global North and its media, for example in the migrant communities’ narrative.

In general, I think that my responsibility as an artist is to create tools that everybody can use, including younger people, to make complex things understandable, and talk about complex issues in a simple way. Working through images is a way of doing this.

For Hidden Histories, you’ve been invited to work in relation to a public monument, specifically the equestrian statue of Anita Garibaldi on the Gianicolo hill, in Rome. You have been working on monuments for several years now, especially on colonial and patriarchal monuments and their implications. When and how did you start working on this issue as an artist?

My research started with analyzing the imperialist and colonialist symbols Spain uses to construct their national identity. These symbols have persisted throughout the years, in different contexts and moments in Spain’s history: during the dictatorship, democracy, and monarchy. The first symbolic reference I decided to work with is the celebration of Spain’s national day which falls on October 12th. I started first at the chocolate store where I used to work because cocoa is obviously a colonial product. Meanwhile, I also approached representation in the public space and decided to analyze the monument of Columbus in Barcelona, by focusing on the image of an indigenous kneeling in front of a priest in the basement of the monument. I made a visual analysis of this monument, in a black and white video called CP12.

The fact is that colonial monuments do not only represent and honor white male murderers who have imposed an exploitation system in the global South; they also represent racialized people from the global South, and they do it through the lens of paternalism. Racialized people are always represented naked, vulnerable, humble, and so on. Racism always swings between paternalism on one side, and criminalization on the other: between the representation of the poor migrant that we need to help, and of the bad criminal migrant that we need to deport. Monuments are an important space where this paternalism is built. These kinds of representations are necessary to maintain the institutional racism that structures today’s societies.

I also found the interaction between tourism and colonial monuments interesting, as they are a big part of the European touristic industry. People go see and take photos of statues that are clearly intended to reinforce the notion of Europe, and concepts such as Western superiority and civilization, the idea of conquest, and so on.

Obviously, in the places where I used to go as a militant, there were people approaching monuments from a more practical perspective. From a historical point of view, attacking and tearing down monuments has had a big part during popular uprisings and revolutionary processes. It is an anti-colonial practice that has always existed.

Is it ever possible to re-signify monuments? Or is removal and destruction the only necessary course in cases such as the Columbus monument? I’ve just read a book by Italian-Srilankan writer Nadeesha Uyangoda, who, discussing this topic, recalls what Franz Fanon wrote in the opening words of The Wretched of the Earth, that is “Decolonization is always a violent phenomenon”—and she adds, “decolonization is not academic theory, but practical action.”

Well, let’s start by clarifying that there is a difference between tearing down and taking down a monument. Sometimes institutions and city councils choose to take down a monument and the discussion ends; they put it in a museum, where they keep it, until one day, maybe a town mayor will decide to put it back, as it happened in Argentina with the Columbus monument. On the other hand, the process of tearing down a monument is completely different. If you analyze the moments when uprisings have exercised this kind of practice, you will see that the main issue of the riot was never tearing down the monument itself, rather it was always some kind of claim in regard or against the system. For example, the recent claims of Black Lives Matter were never only about the offensive, racist nature of the monuments in the street. They were against the incarceration system, against police violence, and against the structural racism imbuing the capitalistic system. Monuments were torn down, police stations were set on fire, and luxury stores were attacked. It’s a big political process that cannot be contained. Tearing down a monument during a popular uprising it’s a way to effectively create a different imaginary. You are changing the way history will be told. Re-signifying monuments is like putting a patch on a rip.

Do we need new monuments in place of those that are torn down?

Well, we could make beautiful monuments! I don’t understand why Europe likes those grey monuments, with that harsh, serious aesthetic. Monumentality in the area where I live is very different, colorful. Cusco, my town, has a monument to corn; in the next town, they have a potato at the center of the square. Obviously, I do think that discussing how to represent society in the public space is important, and I also think that it’s equally important to create new monuments for anti-colonial leaders in order to start and remember colonial history from the side of the resistance. But we could also make monuments to daily life, such as those I mentioned before: potatoes or corn! They are beautiful because they are a recognition of life itself, daily life. You don’t always need a heroic moment. They testify of another way of perceiving life and of what is crucial for society.

Returning to Anita Garibaldi, her story begins in South America, where she was born and where she fought for the Riograndese Republic together with her husband Giuseppe Garibaldi, before coming to Italy. Did you already happen to come across her figure and story? How is she perceived in South America?

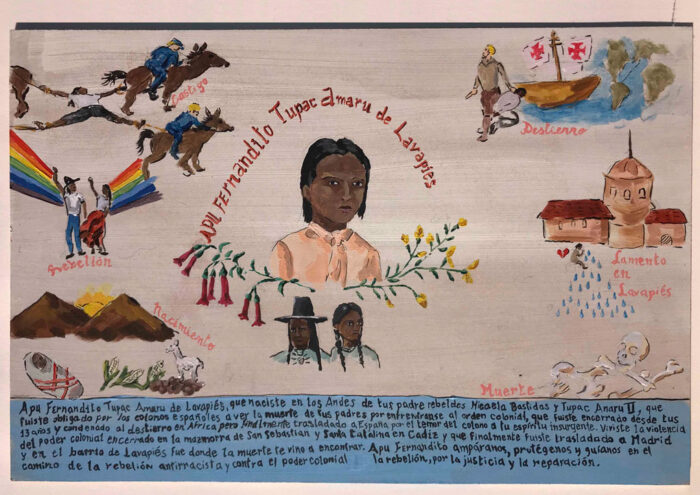

She is not so well known in South America. Obviously, you know who she and Garibaldi are, but Italy has built an image and a significance for them that in Brazil and Latin America they do not have. They were white people, Anita was born from Portuguese parents, so they are more connected to the colonial narrative in the end. Keep in mind that at that moment, anti-colonial uprisings and organizations of racialized, black and indigenous people were very radical. Personalities such as Bartolina Sisa or Micaela Bastidas, the wife of Túpac Amaru, were anti-colonial leaders, real symbols of local history. What was happening in Brazil at the time, with Anita and Giuseppe Garibaldi, was a quest to change the system, not a fight against colonialism. Micaela Bastidas and her husband fought for the independence of indigenous people in Peru, they were killed and destroyed, in the sense that it was forbidden to even talk about them because their project was not compatible within a nation-state, it wasn’t meant to reproduce European institutions in Latin America, such as the republican institution.

In the equestrian monument, Anita appears bare-breasted, holding a gun in one hand and her baby in the other. This representation has been explained through an episode of her life (which we do not know whether it really happened or if it is just a legend, as most information about her). But indeed, we know that the baby was added only at a later point because her image was considered more convenient that way: she had to represent first and foremost a maternal symbol for the country. You have worked a lot on the topic of motherhood, and more generally on parenting. Just to give an example, we could mention your recent book Papa Patriarchy. Is this an aspect you will also be working on here?

I am actually working on the presence of the baby in the statue and around the process of appropriation of Anita’s figure and more generally of the concept of motherhood that Fascism and Mussolini have carried out in order to impose certain narratives and control ideology. This has much to do with the way Totalitarianism acts but also relates with what is happening today, in current societies, regarding the strategies used by politics to direct the way we interpret life and life values. During Fascism, many spaces and organizations for children and young people were created, such as Figli della Lupa or the Opera Nazionale Balilla. The regime produced its own fascist children’s books and tried to control the narrative of motherhood. But there is a kind of inner contradiction in Anita’s monument: if a fascist had met a woman like that, with her character, with a gun and a child, running away alone, he would have arrested or killed her. She can exist like this only as long as she is part of the fascist narrative. I will work on why it was important for Fascism to lay claim to the narrative of childhood and motherhood, and I will try to reconnect all this to nowadays colonial and fascist institutional violence towards mothers and children, especially when it comes to the process of removal of custody. Fascism and colonialism are not detached, you can perceive it in the way social services work: they can persecute a white woman because she is a sex worker and take her child away; but they can also take away a child from a Muslim mother because she is Muslim, even if she is in her house and she is not a sex worker; or from a migrant mother, by the sense of being migrant. This way of interpreting what is a good childhood or good motherhood has to do with ideology and it’s not so far from what Mussolini tried to do with the symbol of Anita. Usually, I like to work with popular artistic materials. I am currently working with religious banners for another project; I’ve done children’s books and ex voto; this time I’m going to work with puppets.