All Pieces Come Together, in the End

Barbara Casavecchia in conversation with Susan Cianciolo

This chat took place at Martina Simeti’s gallery in Milan, that is also a home. Susan and I sat on two chairs next to a long table where she had installed one of her Games, conceived together with her daughter Lilac Sky: a “collage” of fabric off-cuts and found objects, with a set of lanes on one end, with pawns made of drawings, fragments of tiles from the beach, a half moka pot. Everything can be moved, but no rules are provided. All interaction needs to be invented and negotiated: a good metaphor for creativity, as well as for establishing a conversation on unformatted tracks and letting it unfold freely, taking turns to make one’s move. It made me think of Maria Lai’s board games and DIY card sets for discussing art while playing with it (I luoghi dell’arte a portata di mano, Art Places at your Fingertips, 2001).

The chat was not recorded, by mutual decision. It is hence the result of many pages of densely scribbled notes, the leaps of individual memory and the omission of remarks that are just too private or intimate to be reported. It’s an assemblage, obtained by cutting, pasting and joining together many bits, like Susan’s beautiful works, where cloth, paper, paint, threads, plastic, safety pins, tape, nails, glue, objects and materials of all sorts come together in harmony. Thank you for reading.

Barbara Casavecchia: Your tapestries are the result of months, if not years of work. You started most of them during your residency, first in Milan and then in Sicily, at Martina’s family house, and kept working on them, in between travels back and forth New York. Many are the results of gifts and exchanges with a group of old friends and new acquaintances, and you often include very personal items, made with your daughter, or coming from your family, as if traveling also back and forth in time. How and when do you decide a piece is finished?

Susan Cianciolo: I can only tell what usually happens to me. There is an “aha moment”, and it’s always a mysterious and emotional experience. Tapestry is such a beautiful and old practice. I relate it to alchemy. I was not meant to do a tapestry show, it just happened. I realized it on the day of my departure from Milan in the late summer, after the weeks spent in Sicily. The work has its own voice. I’m just a person with hands. The work wins.

Susan Cianciolo at Martina Simeti Gallery, Installation view. Courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York and Martina Simeti, Milano. Photo Andrea Rossetti.

Susan Cianciolo, Woman on the Beach with Diamonds, 2019. Courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York and Martina Simeti, Milano. Photo Andrea Rossetti.

Why did you pick GAME ROOM, NATURE MAZE: To Live A Life on Earth is one of the Highest Honors as title for the exhibition?

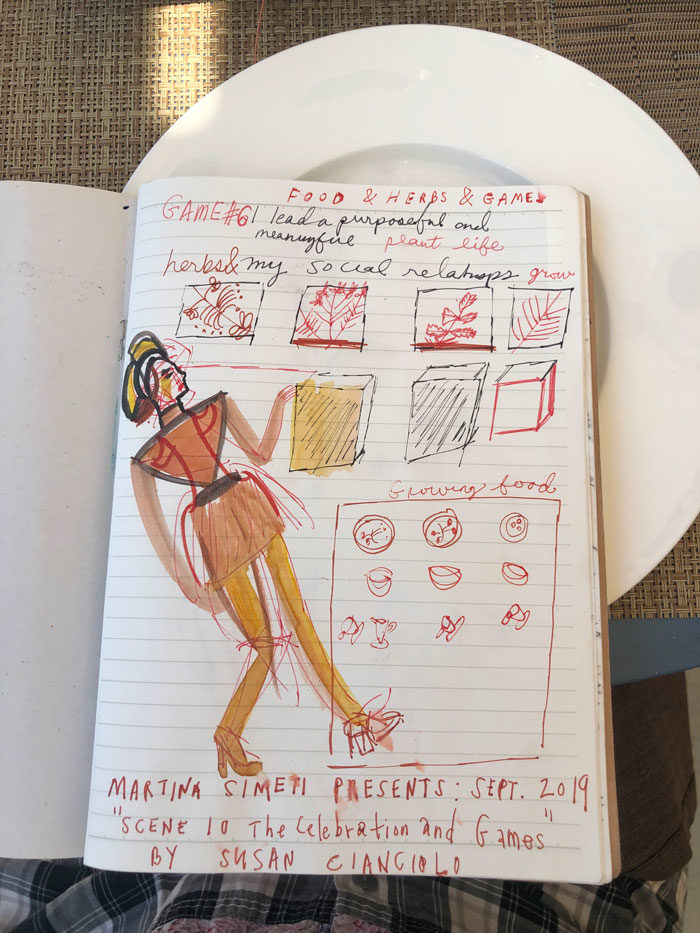

I have sketchbooks for every body of work—they are handmade books, like the one just published by Nieves Book, I Love You (2019). I was browsing through the pages that I had put together during my stay in Siena last year, when I was also collecting, drawing and painting botanical plants, and I found an old note that said: “Game Nature Maze.” It was a vision I had through meditation. When you relax, your perception of reality becomes abstract. I guess I’ve been playing with these three words at the back of my mind for a really long time. When I remembered them, I decided to use them as the title for this exhibition.

Finding a title is my favorite part of each show. I come up with hundreds of names, and then click, here’s the one. Sometimes it takes me days or even months, when I don’t socialize much and prefer to be on my own. I can’t find anything, when I’m immersed in daily chit-chat, I need silence.

Susan Cianciolo, Untitled (tapestry), 2016. Courtesy Bridget Donahue Gallery, NYC, and Martina Simeti, Milan.

Since you mentioned alchemy and meditation, let me tell you a story. I have recently visited an exhibition on Emma Kunz (1892-1963) at Museum Susch, in Switzerland, and I think you’d love her drawings. I know you are very fond of Hilma af Klint, with whom Kunz is often associated. She started creating her drawings in the late 1930s and never exhibited them as artworks. She considered them as “tools” of her healing practices, based on the power of nature. After meeting her patients, Kunz would mark a set of fine dots on graph paper with the help of a divining pendulum. Then she literally connected the dots and created these incredibly, obsessively intricate large colored drawings, composed of thousand lines, where abstract forms emerge from the layering of geometric elements. After the drawing was finally completed, Kunz would summon again the patient to propose a treatment or cure, as if that long process of visualization helped her ‘see’ exactly what needed to be solved. She only published two small books, during her entire life, with almost no comment on the meaning of her pieces: most of what we know about them comes from third parties, so that it could be largely fictional. And yet, it’s hard to resist their hypnotic fascination. The repetition of certain patterns and elements, as in mandalas, seem to knock on the doors of perception.

What an extraordinary story! I practice meditation on a regular basis and I visualize abstract shapes— spheres, spirals, in black—coming at me, so that I’ve started to record them in my notebooks with drawings. I too firmly believe in the power of repetition, because it is part of the natural harmony, part of its beauty. For instance, I’ve always liked to repeat my performances over and over again, across the years. Like Sleepers, for instance. From the viewpoint of a designer, it’s clear that people will always want something new, but to repeat an idea until it becomes familiar brings about so many fascinating aspects.

Maybe repetition is also a way of healing myself. The wish to talk about healing is one of the reasons of my being always so apprehensive about interviews, now, because no one likes to sound like an insane person… It’s a topic that used to be pretty taboo, although I think that it’s now becoming more comfortable to discuss it. People seem to be more open to it.

I associate repetition with the iterative processes of so many physical practices related to discipline, like yoga or dance: the body repeats a set of movements until it slowly forgets all about technique and instructions, and keeps on exploring them over and over again, along a sort of circular path, where mistakes are not only allowed, but useful.

While in art there are no rules, meditation is very disciplined, and I like to push things far, mentally. I can wrap myself up in discipline, but i also think that we came to this earth to be human and for the enjoyment of every moment. At my age, i guess i’m trying to find a good balance, to have a wiser time management, and to avoid abusive self-punishments leading to burn out, as in the past.

I think I understand, to be honest.

Experiencing a burn out, means going through the big change of being vulnerable. We have all guards up. All walls come down. I try and remember it, and also use it, now that I’m working as a teacher.

Susan Cianciolo, Residency at Martina Simeti.

Where do you teach?

At Pratt Institute, in Brooklyn. With students, we discuss on how to learn together, and be honest, and build a sense of confidence, and face mental issues. We do a lot of exercises. And I am also struggling with writing my dissertation, at the moment.

Writing too is a practice full of repetitions, layers, additions, reworking—anything but linear. And it involves many hands, pretty much like quilting.

I like repetition also in games. Why should there be rules? In London, where I presented some Games at the South London Gallery (for Cianciolo’s solo exhibition God Life: Modern House on Land Outside Game Table), a young game keeper became really dedicated and kept playing and playing. Kids are wonderful at invention. All day and night is a game, not only as a form of entertainment. The deeper part of life being a game, not taking it so seriously is very wise. I love it when you just play and let go. Being a mother can be very monotonous—a very mundane kind of existence, sometimes. Jokes keep me going, the kind of things you share with friends. At RUN we had all sorts of inside jokes. We would make things that were very funny. They were our forms of entertainment.

Susan Cianciolo, Spirit Guide, 2019. Courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York and Martina Simeti, Milano. Photo Andrea Rossetti.

Was there some irony, too, in your decision to work mostly with second-hand materials, when you started RUN in the mid Nineties?

My fun is not being stuck with tradition. Anyway, I was never into shopping for new things. Thrift shops provided me with all the excitement of treasures. I’ve done a lot of trading and I’d rather exchange materials and clothes. In my philosophy, it’s about an idea of community.

Here, you see? This centrepiece is the outcome of a big collaboration with Thompson Street Studio in New York. We work together often, I send them something, they work on it and send it back to me. Each time, we add something to it. A friend gave me this piece of fabric, which makes it special. It’s such an overused expression, but “you’re one of a kind” is so true!

This is made out of an old blanket that I found in the woods, under a pile of leaves, near Martina’s house. This old jumper was given to me by her cousin Natalia, and this is a beautiful African rug that Martina had in her trunk. These are pieces of fabric or plastic that washed up on the beach. They embody the whole residency and the memories I brought back with me to New York. The colors, the shapes and the images become a big, layered and beautiful collage, encoded in stories that you weave and stitch together. My mantra is never to waste anything.

…

I’ve always had an instinct for material, my costumes include very “poor” fabrics, like polyester. Five years ago I started using plastic and sleeping bags: I leave them out in the open, in nature, or on the roof of my studio, and then go back to them. Garbage left on the corner of the road can offer all kind of discoveries. I also like to “sacrifice” my favorite things, and share them.

The beauty of textiles lays in experience, I think. I’m not talking only about the individual memories that can be triggered by a piece of fabric, or an old garment. Textiles involve many hands and travels across the globe, who knows how many. I had the chance to spend time in Japan, in Kyoto, with textile masters who inherited generations of technical knowledge on weaving and natural dyeing from their family, and it’s been a life-changing experience.

Susan Cianciolo, Tapestry 5, 2017. Courtesy Bridget Donahue Gallery, NYC, and Martina Simeti, Milan.

So how did you build your own experience or, let’s say, expertise?

Sewing is what I’m most trained in. I have memories of my mother teaching me how to cross-stitch. She used to do quilts and she also made dolls for me, as a present, but also because she thoroughly enjoyed making them. Subconsciously, it all got passed on to me. Once she gave me all her pieces, for me to rework, and mentioned that she was also teaching aside. She was an oil painter, and in her days, the professional options for a woman like her were basically teacher or nurse. I was brought up my grandpa, who was of Italian descent, but changed his name from Guido to Hal, because he had married an Irish/Scottish woman and wanted to fit in more easily. She did crochet and weaving. I could have learned so much from all the women in my family, who were truly masters at sewing, but somehow refused to, because I thought “feminine” stuff was too oppressive, while in fact it can be a pretty powerful tool. After getting into fashion school, at Parsons, I realized how many techniques I did not know and needed to learn anew, if I wanted to be top of the game. It took me a lot of work, dedication and time to master tailoring and sewing; on the other hand, I was extremely passionate, when it came to forget about rules and boundaries. For my films, for instance, I did everything: script, costumes, editing, filming, then I could let it go. I’ve always liked to branch out in every kind of medium and disliked being pinpointed. There is a kind of freedom in it.

So what had brought you to fashion, of all fields, in the first place?

I wanted to be a fine artist, but my family told me that I had to learn a trade first, and then do what I wanted on the side. So I did: I learned a trade. Now, basically, I feel great when I deconstruct. I wanted this kind of acknowledgment. It’s not that I feel that making art is any better, it’s just a matter of fulfillment. Now my deepest happiness is being alone in my studio, every day, with the work. Both fashion and art are very physical, anyway. And I love using my physical self.