Age Is a Fraud

On Simon(e) van Saarloos’ “Against Ageism: A Queer Manifesto”

I always had troubles dealing with authority, but I remember clearly the moment when, a few years ago, an epiphany made an appearance amongst my thoughts while looking at a so-called “adult”—it was proclaiming that adulthood is a fraud. After that my eyes began to see things differently, and I started to feel uncomfortable when hearing certain expressions such as “middle-life crisis” or “behaving like a child,” or someone being called “immature.” How limiting and inaccurate were these markers, as if our lives could seriously be a collection of steady introvertible successes, with no hesitation, sentiment, nor way back. How calcifying and depressing it is to think that one becomes only forward, until they begin to wither, and thus become of less use. And how patronizing toward the “old” and the “young” is the usual understanding of care, more intended as guidance than nourishment. All is read through the lens of efficiency, success, productivity, and physical prowess.

Yet, there are plenty of things one can stand against, especially in these crucial violent times we live, sometimes it feels to me, the struggle is transversal and continuous—to dismantle oppressive power structures and infrastructures is a constant labour, and I say labour because it brings fatigue, it requires rigor, and a certain obstinacy to find the bolts that shall be loosened and then removed, it requires a certain strength to think back and think anew as not to return to a recurrent thought or assumption, that is a supposition that descends upon us and depends on presumptions. Inasmuch as we are taught to read time as linear, thus perceive our seasoning as a growing count—we are told to get “older,” more “mature,” “put years on” toward senesce. As the counting increases we are paradoxically supposed to get “less and less,” gaining more and more proximity to loss.

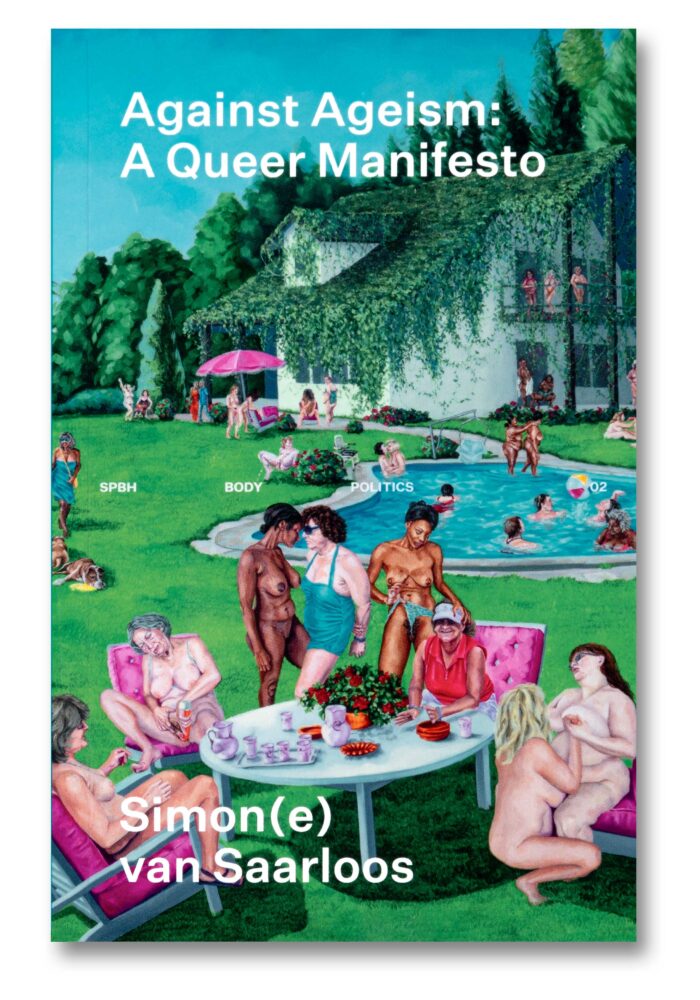

With their book Against Ageism: A Queer Manifesto (MACK, 2025), Simon(e) Van Saarloos gets rid of many of these bolts that hold our assumptions tight, and I must say, it is quite a journey to read through the whole process. T Fleischmann’s title comes to mind—if “Time is a Thing a Body Moves Through” and each body moves at a very different intensity and speed, in following Van Saarloos’s arguments while they unfold, our body goes back and forth and around—becomes quantum in a way ubiquitous, in remembering and recalculating, revisiting and opening new possibilities for repetition, stumbles, reviews down to the spiral of scalds, pauses, stutters, and most and foremost new postures. I feel I should say—there’s no way back to linearity, as the body remains to linger in this perception of a time that is comfortably bent at occurrence, for infinite times even.

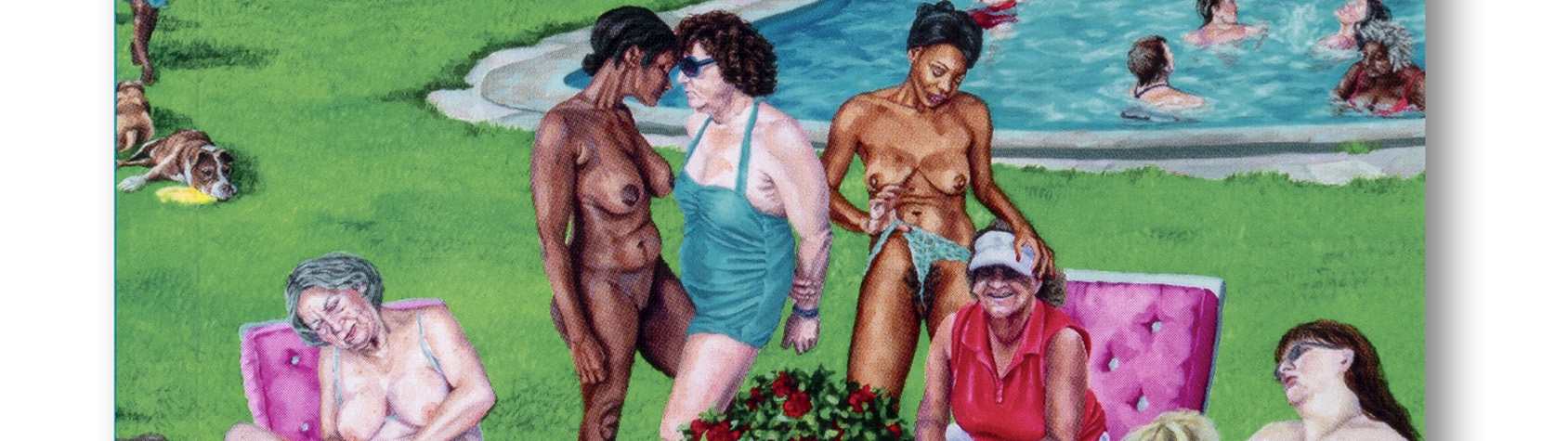

I will try now to recount how they do it, although I feel I could write this again and it would never be the same, as if I am telling a story several times, its intonation would always vary. The claim remains sturdy throughout, age is a white ableist exclusionary construct. As this bolt falls off, many others get loose. Intergenerational love (and lovemaking) is the thread through which this claim is woven, for Van Saarloos writing comes from and happens within their body, and from the claim that “injustice is everywhere.” Against the intrinsic traceability of be it ageism, racism, ableism or gender-related exclusionary linguistics and behavioural automatisms, this very layered fight “means to recognize life without any categories of similarity and belonging.” Ageism and linear time, they argue thinking with Denise Ferreira da Silva and the Black Quantum Futurism collective, are forms of colonial violence, while the stereotypes deriving from it are related to “heteronormative family roles, generational growth, and the centralization of reproduction.”

Still, to loosen these bolts of age and time, several others have to be unscrewed. Van Saarloos looks back to move forward, by refusing the association between childhood and innocence, revisiting their experience of sexual abuse “through the lens of fire,” that is to say avoiding separation between the trauma and themselves, whilst disentangling sexuality from evolution once and for all. Shame, agency, pleasure, and victimhood necessarily come into the picture: “Patriarchy does not just create victims; it creates victims because it needs victims and the condemnation of victimhood in order to uphold carceral and punitive responses to violence.” The phrasing upholds a very clear vision that intersectionally overcomes the patriarchal fantasies of protection, through a trans masculine reading of sexual assault, “toward the abolition of criminalizing categories altogether.”

If intergenerational intimacy is often perceived from outside as a parent-child relationship, as the time gap between lovers becomes role-defining, according to Van Saarloos “straight time”—referring to José Esteban Muñoz—is a paranoid and “a doing-it-right” kind of time, “an assumed temporality.” Queer love suppresses this linearity and regularity, opens up endless possibilities of (sexual) roles and plays, names, families, “without an attachment to the end goal of settling down.” Life can begin anew each time we meet another body, or are born again with another name. All these stigmatizing expectations can be called-out, as embarrassingly predictable as they are, and Van Saarloos does so inspired by Adrian Piper’s Calling Cards, demanding a correction but fore and foremost by creating a space to imagine other ways of interacting.

At a certain moment Aristotle literally comes into the picture, by way of contrast as the old white man canon to pontificate on the characters of the old and of the young, and immediately after that temporalities are reoriented, bended, disrupted with JJJJJerome Ellis’s poetry and Alison Krafer reading of “crip time” that considers the diversity of bodyminds: “rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds.” We all know how violent this capitalist time can be, and how could we (meaning all of us) each proceed at their own pace—against the use of time as a gatekeeper, and velocity as a marker of quality. Like with architecture, these indicators prevent many people from participating in our society as it is. Age is used as a measure of capability, and as signifier for one’s desires and positions, when aging is a privilege in itself, as “white, able-bodied people get to grow toward death, while Blackness and disability are conflated with death and categorized as inanimate.”

In these normative temporalities, an elder is often excused for being racist—as if racism would be “backward or old-fashioned. This places racism in the past, leaving the present unchallenged.” Indeed, time is usually used as an excuse, as a divide-and-conquer segregative tool, and regulatory force, for the only progress is toward a Western enlightenment, and the future a desirable hub one can buy (through accumulation of wealth): “our grammar on age teaches us that children are a symbol of potential, while the elderly are perceived as the antithesis of progress. The elderly hold tradition and memory, not innovation and future.” With the help of Black Quantum Futurism, Van Saarloos breaks this down by pluralizing existence, change, and interdependency, and insisting on the locality of time.

How coercive is this pretense that according to your age you should behave in a certain way, and normalize certain limitations? Van Saarloos discards the measurement capability to “create” for which the body is turned into a societal norm. By picturing the building of a “normal” baby-citizen, their imagination can spirally expand: “What is included in the category of ‘normal’ does expand, but the measurement called ‘normal’ does not budge. I describe this onslaught of images because it furthers my inclination to demand that we abolish the military, the militaristic epistemology of border control, nations and nationality, invasion, and non-consensual penetration. And while we’re at it, let’s abolish tracking, monitoring, and measuring as a necessity of life.” And perhaps also let’s stop considering parenting/teaching/loving as a coercive “let-me-show-you-the-way” practice? Once this structure has fallen, a whole new web of relationships can be built.