A World with No Water

How can we nurture the imagination of a catastrophe to come, to act and survive beyond this irresponsible eternal present?

The exhibition Post-Water, curated by Andrea Lerda at the Museo Nazionale della Montagna in Turin, unfolds through a narrative path on the theme of water, articulated through video, photography, drawing and sculpture. The exhibition is part of a global debate on a theme of great collective urgency. Water, the most essential natural element that generates and guarantees the maintenance of life, is only one of the goods that suffer from the acute crisis of the sense of responsibility of our time. The following is one of the essays from the exhibition catalogue (Museo della Montagna, 2018)

Water will run out. As legends brought by weary travelers we begin to feel that water is in shortage, but it is lacking in places so far that our showers continue to flow like fountains and our lawns in the garden are bright and florid.

These sad and imaginative legends tell of polluted aquifers, of deserts that advance, and some absurd stories resemble the echo of dystopias and conspiracies, in which the princes of profit and the oligarchs of the night are grabbing all the sources of the earth. Some of them would be building huge dams, which dry the lands of poor people downstream. Others would be closing access to huge underground lakes, waiting for future aridity, to tap with the dropper and at a high price the essential element of life, just like locking a safe. But not now, right? Maybe tomorrow, or in a remote day after tomorrow that does not affect us. Instead it is happening now, and we do not even need to gag Cassandra, because almost everything in our present has educated us to the Great Ucronia.

Adam Jeppesen, AR Chalten I, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Martin Asbaek, Copenhagen. Vejle Kunstmuseum Collection

Macroeconomics, which once thought in terms of decades, is currently content to foresee a quarter, neoliberal consumerism tells us that everything is immediate, the denial and oblivion of history are educating whole generations to the here-now of the network, post-truth trains the minds not to train any more, to renounce critical thinking, analysis, even just common sense.

Jared Diamond has written hundreds of pages to try to understand how many cultures of the Earth have experienced a socio-economic collapse without being able to realize the catastrophe that was coming. Hundreds of pages that, from Easter Island to the Greenland of Icelandic settlers to present-day China, want to explore historical myopia, the inability to read the signs, the tendency to look the other way because in a mixture of arrogance and of metaphysical hope we come to believe that everything will one day be fixed, that everything will be sorted. It is as if an information trap was embedded in the genetics of our species, leading us to think for the best; that no, it isn’t really happening to us.

Giuseppe Penone, Alpi Marittime. La mia altezza, la lunghezza delle mie braccia, il mio spessore in un ruscello, 1968 (Ed.2/3). Collection MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna

It is what Bruce Chatwin had observed interviewing Bob Brain, a paleontologist who had studied the bone findings of Dinofelis in South Africa. The Dinofelis was a kind of saber-toothed tiger living a million years ago that almost exterminated man. It “liked” us, so to speak, but just in the nick of time, we discovered fire and narrowly escaped extinction. To understand the Dinofelis, Bob Brain had studied the behavior of the current big African cats, especially those who prefer to eat primates. In this way he happened to observe the behavior of a group of baboons who lived on the edge of a cave of volcanic origin. The bottom of the cave was a network of tunnels where a leopard lived. The leopard moved at night and whenever it felt like it, it was helping itself on the edge of the cave: it was sinking its teeth into a baboon and dragging it away, holding it by the head or shoulder, in the darkness of its den. The baboons cackled madly every time the cat appeared, but they did not leave the cave, they remained there, in a strange unstable balance between fear of the monster and fear of the night.

Bob Brain also carried out an experiment. He recorded a series of leopard calls, hid in a cave that housed another community of baboons and at night the recording was played back at full blast. The baboons screamed madly, but this time they did not flee, they remained there, chained to their disturbing and inexplicable comfort zone. But what was happening in their heads? Why did they accept coexistence with pure horror? What drove them to inaction, to not reacting for survival? Chatwin could not answer, but he suggested to us the idea that perhaps their minds were crossed by a single, dull, irresponsible thought: this night it’s not my turn.

Francesco Jodice, Aral_Citytellers, 2010 Film HD, 48’06’’. Courtesy the artist and Michela Rizzo Gallery, Venice

A thought that is not composed of the optimistic fabric of hope but, on the contrary, originates in the biological candor with which we know that we are disinterested in the destiny of those around us. It is as if we had in our brain a gene that helps us to ignore the hunger, suffering and death of others; a kind of block of empathy that prevents us, if not at the price of some effort of imagination, to identify with for example a child dying of thirst in sub-Saharan Africa, or a migrant drowning in the Mediterranean. So it’s not our son, or our brother, is it? Gaston Bachelard wrote immense pages on water, but the most important thing he did was to make a double symbolic link between water and the imaginary. Not only does water bring complex images with it, but the imaginary itself is the bearer of a sort of aquatic phenomenology, it behaves like water: it flows, adapts, moistens and raises the thought process, and obviously can dry up.

The main problem in our current way of approaching the ecological Dinofelis, which lurks at the bottom of our near future, is precisely the drying up of the imaginary, our inability to irrigate the thought of vicarious visions that are capable of anticipating the future, to make predictions, to identify ourselves with who will come. Let’s try instead to imagine that the Dinofelis, this night, will come to take us or one of our children. Imagine their terrified eyes, their back dragging on the cobblestones as the monster drags them into its dark lair, let’s imagine the moment when the smothered pupils fall back into their sockets because the fangs have interrupted their lives. Lucretius spoke of beasts and imagined the flesh of primordial men who were buried in the living graves of these beasts, in their furious stomachs. Imagine. But imagination, like water, goes away, and must be nurtured. It is not unlimited, it is not easy to collect and use.

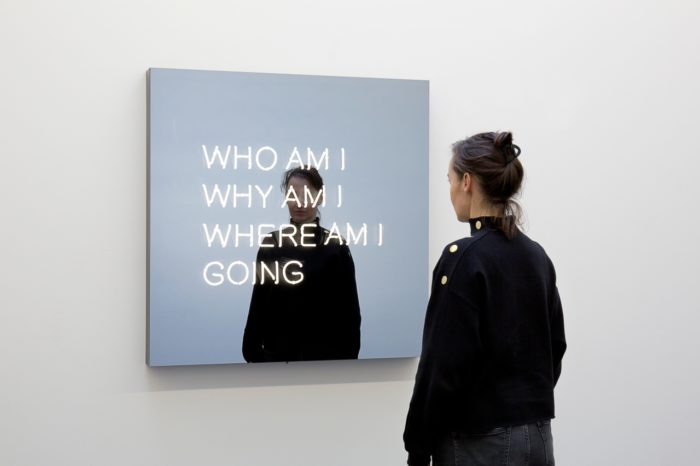

Jeppe Hein, Who Am I Why Am I Where Am I Going, 2017. Courtesy König Galerie, Berlin, 303 Gallery, New York and Nicolai Wallner Gallery, Copenhagen Photo credits Studio Jeppe Hein / Florian Neufeldt

Almost everything today is distracting us from individually training the imaginary, as well as making us accustomed to living in a kind of irresponsible, eternal present. Search engines always have a first answer that we can “drink” readily, the flood of information covers the blanks and their creative potential, the practices of searching for ideas and images on the net are so automatic that on one hand we no longer want to memorize anything, on the other we postpone every true search to tomorrow, it’s all there anyway, forever. Yes, maybe. What we do not think about is that the access systems to that everything, the order in the answers, their quality and truth have been decided by others, because not only are we crazy enough to delegate the management of power and our lives to third parties, but also the imaginary and, even before water, there are those who are storing it according to their priorities, there are those who are raising dams to contain it and redistribute it according to their own rules. But if the flows of the imaginary are controlled, if we lose the self-management of images, then the first thing we will stop doing is imagining ourselves, and imagining others.

Post-Water, Installation view at Museo Nazionale della Montagna, Turin

And then the images of us and others that will have decided in our place will be enough, we will be conformist in everything and accept to place our trust in the enemies, without even making a personal effort to understand if they are really enemies. Marina Abramovich, inspired by facts portrayed daily in Italian news regarding the management of migrants at sea, used the slogan “we are all in the same boat.” Now, in ecological terms, this boat is the planet that hosts us. Water is beginning to be in short supply far from our nose, far from our lips, but it is already lacking, and the apocalypse of dystopias and plots is already reality in an elsewhere that sooner or later we will be forced to look at. But when we do it it will be too late, because perhaps this night it is not our turn, but it will touch us tomorrow, it will be our children’s turn, it will touch who we should have been capable of imagining but we did not. Not only has the myth of Narcissus to do with an obtuse falling in love with himself. It also has to do with those who notice too late they are slipping into the abyss.

Marcos Avila Forero, Atrato, 2014. Video HD 16/9, color and sound, 13’52’’. Courtesy the artist and ADN Galeria, Barcelona

Imagine then a desert world. Made of peoples who migrate, with no destiny, along a salvific and delusive path of water. Every now and then, on the way, there are towers that guard small springs, and at the foot of these towers people fight each other, with sticks and stones, with their teeth and nails. Then, one after the other, even the water towers will dry up, the peoples’ bones will bleach and everything we have written, said, loved, imagined will be lost forever. Like water in the sand.