A Voice Telling a Story

A conversation with Adila Bennedjaï-Zou about hidden histories and oral literature

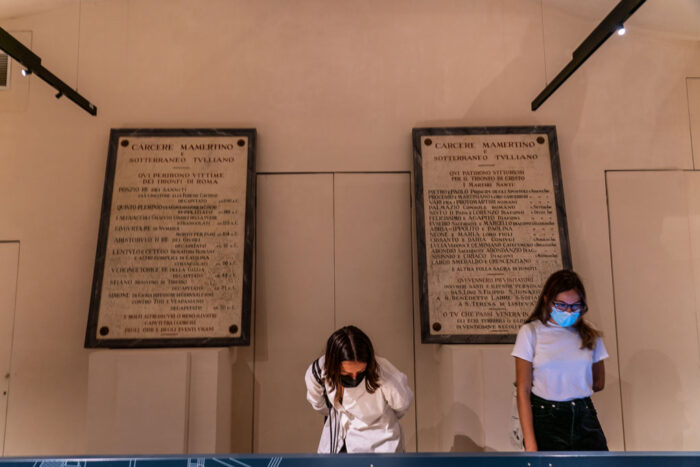

As the closing act of Hidden Histories 2021, on Saturday October 2nd, artist Adila Bennedjaï-Zou guided the audience through her sound creation at the Carcere Mamertino, in the context of the Roman Forum. The prison, mostly known to have confined St. Peter and Paul, was also the tomb of Jugurta, king of Numidia, who stood up to the Roman Empire. Together with members of the Berber community in Rome, the artist organized a convivial moment in order to celebrate the memory of Jugurtha, a historic presence hidden from the predominant stories that narrate the area of the Roman Forum.

The following conversation, which took place after the event, traces the birth of this project and introduces other works developed by the artist in the months she spent at the French Academy in Rome, Villa Medici, during 2020–2021. Bennedjaï-Zou’s words deepen her interest and research into the potential of the voice, and present micro-history as a way to overcome the violence and rhetoric of hegemonic narratives.

Hidden Histories is a site-specific public program, consisting of performances, workshops, talks and urban explorations, meant to reflect on the cultural and historical heritage of Rome from a decolonial perspective. Conceived and curated by LOCALES, a curatorial platform founded in Rome by Sara Alberani and Valerio Del Baglivo, the project presented this year its second edition, which ran from June to October and included interventions by Stalker, bankleer, Josèfa Ntjam, Leone Contini, Daniela Ortiz and Adila Bennedjaï-Zou. As the program unfolded, a series of interviews conducted by Marta Federici with the artists of HH 2021 explored their research and provided a broader context for each.

Marta Federici: You are both a screenwriter and an artist. Presently, you are making sound documentaries but have also made films in the past. Image and sound, how do you handle these two media languages?

Adila Bennedjaï-Zou: I was writing and making films when I discovered sound for the first time and immediately preferred it over other media. I sometimes however still write movies for other people, but when it comes to my personal work, unless it is an extremely visual subject, I generally prefer to use sound because it gives me more freedom, also in terms of money: working with sound is undoubtedly cheaper than making a movie. Movies always cost so much, and when someone gives you a lot of money, they also expect a lot. When you work for TV and cinema, you must write, rewrite, and then rewrite it all over again, because people working in that industry want to know beforehand how the story will unfold down to every single detail. Instead, with sound, I have experimented with the possibility of beginning something without knowing where I was going, and in the end, this kind of attitude has become essential to my practice. If you already know what you are going to say, you end up not going anywhere: you are bound to lose your critical sense. But there is also a second reason for which I prefer sound, a logistic aspect in this case, related to the fact that I often work within people’s intimate sphere. I ask several personal questions to the people I meet; I really get into their personal and most private space. From this point of view, sound is great because it’s more discreet. If I showed up with a camera it would take weeks before a person would let me talk with them intimately.

Your works usually compare two different levels of history: the macro-level of the great narratives—the hegemonic narratives—and the micro-level of individual existences. How do you interpret the dialogue between these two dimensions?

I simply think that we cannot make history without that kind of dialogue. I place myself in the heritage of micro-history, a historiographic research movement that emerged in Italy in the 1970s but gave birth to some beautiful works also in France. Great history is nothing, it is just propaganda. If we want to restore the complexity of the past, we need to mix different threads.

How do you usually choose the stories you want to tell?

I always work on matters that concern me. This is an important aspect of my practice: my work springs from my point of view. Subjectivity is another element I discovered when I first approached sound. In the past, I used to make documentaries with what is understood as the standard—yet only apparent—neutral vision, but I can no longer do that because I think it is necessary and more honest to clearly state what position one is speaking from. By doing so, the person who watches or listens to my work can also express their opinion, they can disagree with me. Because I know that I am not telling the truth, I am telling my truth.

When I choose to interview someone, I choose a story, a voice, and a way to tell that story. Ira Glass, host and producer of the radio and television series This American Life, once said that good stories always happen to people capable of telling them. But also, people are not always able to tell stories as it depends on what stage of life they are in. For example, when I choose to interview a person with a very dramatic story, usually they are at a point in their life where they have already made something of that past condition. No longer being in the middle of the tragedy allows a person to make sense out of the situation. I couldn’t interview someone amid their own personal tragedy.

You usually adopt a documentary approach in your work, but you have also written works of fiction, and it seems to me that the two approaches sometimes blend within your practice. How do facts and fiction contribute to shaping reality? Is there a point where these two narrative strategies meet?

I think they converge in two ways, in two main points. First, I write my commentaries in my audio documentaries, so I am still a writer. Second, I am always a storyteller. Indeed I am obsessed with storytelling! When I approach a subject, I obviously know that particular subject interests me, but I am not sure whether it will also capture someone else’s attention. I need the people who listen to my story to be captivated! I need to hook them, and to achieve this I use storytelling techniques. These are rhetorical strategies, like entertaining the audience with humor, or drama, or suspense. In documentaries, you don’t have many plot twists, but you can use other expedients such as making your audience change their mind about something as the story unfolds. Change their opinion about a character or a fact, depending on how you construct the narrative. That is where I intervene.

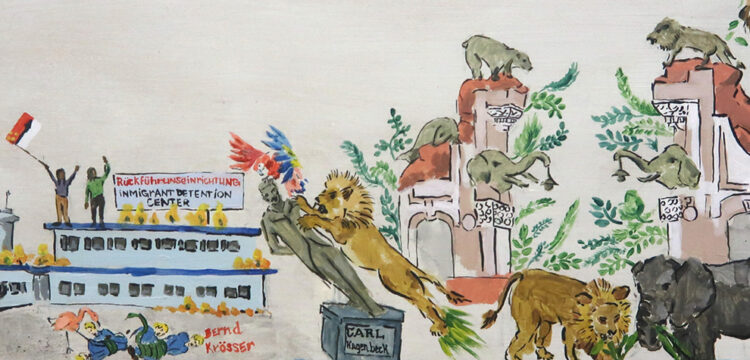

Last year, during your residency in Rome, you made a piece about a series of tapestries exhibited in the great hall of Villa Medici, called Des Anciennes Indes (that means From the Ancient Indies) depicting exotic landscapes and exoticized nonwhite people. You wrote a text which restores the story of one of these figures in the form of a “fictional but possible” autobiography, giving him back a name, Miguel De Castro, and a proper place in history. I was wondering if you could tell me more on this work. In the first lines of the text, you stress the need for this act, as a reparation of memory, against the violence of a history which has always been written by white men for white men, but you also point out how this kind of work cause you fatigue and exhaustion.

I have just given a lecture about the story of Miguel De Castro, a couple of days ago, and I cried when I finished. In a way, this work and research were truly conflicting for me. It’s the trap of the assignment. At the beginning, when I first saw the tapestries, a part of myself obviously felt concerned about them, and knew that it was something I wanted to work on. However, at the same time, another part of me opposed it and dwelled on whether I actually had to follow through since I was in Rome for other reasons. I am always fighting with the assignment coming from the outside: I refuse it, but at the same time I also feel pressured by something else coming from the inside of myself. It is complicated. I fight with what I am and with what people expect from me. And also, consequently, I fight with what I expect from me.

Coming to the story of Miguel De Castro, when I arrived at Villa Medici some people were saying that those tapestries were racist—and indeed they are. I started to research them, and I discovered that a scholar had identified one of the men depicted in the tapestries, so I decided that I had to tell his story. The first violence that was made to those people was reification. They were transformed into objects, fictional characters. By telling this man’s story as a speculative biography, I wanted to give him back an identity. He would no longer be an object or a character, but a person.

As I said, from the very beginning, I immediately felt a connection with the figures in the tapestries, but I couldn’t exactly pinpoint the link. But then, something happened in France. A guy called Michel—that is Miguel in French—was beaten up by policemen in his music studio in Paris. They brutally hit him, called him racial slurs, and so on for fifteen long minutes. He hadn’t done anything. Fortuitously there were cameras, so it broke into a big scandal, and several demonstrations ensued. With the other fellow artists in Villa Medici, we talked a lot about this story, and I told them that it was because of the tapestries that Michel was brutally beaten up. But they didn’t really understand. Someone even told me that I couldn’t put all the racist crimes on the same level.

The story of Miguel De Castro deals with slave trade in a complex way. Miguel De Castro was a noble of Congo, and nobles of Congo used to sell people as slaves. He lived before the peak of slave trading. From what I understand studying slavery history, when slavery began it wasn’t because of racism, but racism was used to legitimate it, because it was such an unacceptable crime. So first it was decided to forget everything and then to say the victims of that crime deserved it. I am quite sure that the policemen who beat Michel up were precisely perpetrating a denying: they were beating him to protect their ancestors, and to protect themselves from the ignoble crime of slavery. That’s what I was talking about the other day. I finally found the connection I was looking for. It is the racial order we still live in. I am also in that hierarchy, even if not in the exact same spot as Michel or Miguel.

On the occasion of Hidden Histories 2021, you presented an audio piece in the Carcere Mamertino, inside the Foro Romano. It’s a work dedicated to the memory of Jugurtha, Berber commander and king of Numidia who fought against the Roman Empire. In the work, Jugurtha is remembered through the words of a woman descending from that community, centuries later. How did this project start and evolve during your stay in Rome?

When I met Valerio and Sara, they told me about Hidden Histories, and I immediately fell in love with the project. Today people talk a lot of cancel culture, of removing sculptures, and so on. I think that Hidden Histories represents in a way the positive counterpart of cancel culture. I mean, for me cancel culture is a good thing, because it asks us to look at our space in a critical way, to remove stories that we don’t want to hear or see anymore because they’re offensive or violent. While, with Hidden Histories, we can finally hear stories that we never heard before. So, it’s a counterpart in the sense that it reveals the conflict existing between negative and positive meaning.

Then, one day, I was speaking with a Kabylian friend, and she told me that, since I was in Rome, I had to go and see the tomb of Jugurtha. I looked for it but couldn’t find it, because obviously the Carcere Mamertino is not known for being the tomb of a king of Numidia. I love Kabylian people’s attitude. They are the natives of North Africa and endured four layers of colonization: Roman, Arab, Ottoman, and finally French. After four colonizations, two thousand years later, they are still cherishing their stories, their heroes, and their pride. I love that. Still today, they are oppressed by the Algerian government, but they keep on fighting. For me, it was obviously a hidden history to be told.

The words of Mazhour Hammache, the woman you interviewed and that we hear in the audio, intertwine the forgotten history of Jugurtha hinting at the situation of wider invisibility which still invests the culture of the Berberian people today. But her narration doesn’t really explain all the things she mentions. As if completing the story was the listener’s responsibility.

Well, I wanted to make a short piece and I did want to preserve its emotional feel. Mazhour had told me more than what you hear, but when I edited it, I decided to cut some parts. For me, the most important aspect was to make people understand how her culture is vulnerable and that she had fought for it, but I didn’t want to give away too many technical details, as they could have distanced the audience. So yes, in the end, this way of working makes the audience more responsible to go and look for more information. It’s always difficult to find the right balance, nevertheless, I believe it is more important to hear Mazhour’s voice, the way she talks and tells things, rather than the facts themselves.

A voice telling a story: it is what happens in most of your works. I was thinking that orality represents an ancient way of transmitting memory and knowledge, an alternative to the written word and, I’d say, closer to the dimension of the community. Is this also an aspect that influences your choice towards the use of voice?

I think that I have a different perspective on this. You know I’ve done a lot of podcasts, and that people usually listen to podcasts in their headphones, alone. What I believe is that oral interviews are creating a kind of oral literature. The way a person speaks, their voice, tells a lot! You lose a lot of information in a transcript text. Even if you follow exactly what the person is telling you, and you try to keep up with each word and pause, you will still lose the silences, you will not hear the accent. Through someone’s voice, you can perceive their emotions, social class, the relationship they have with the interviewer. A person is made of countless little details, and that can’t be expressed in words alone.