A Tiny Town South of Rome

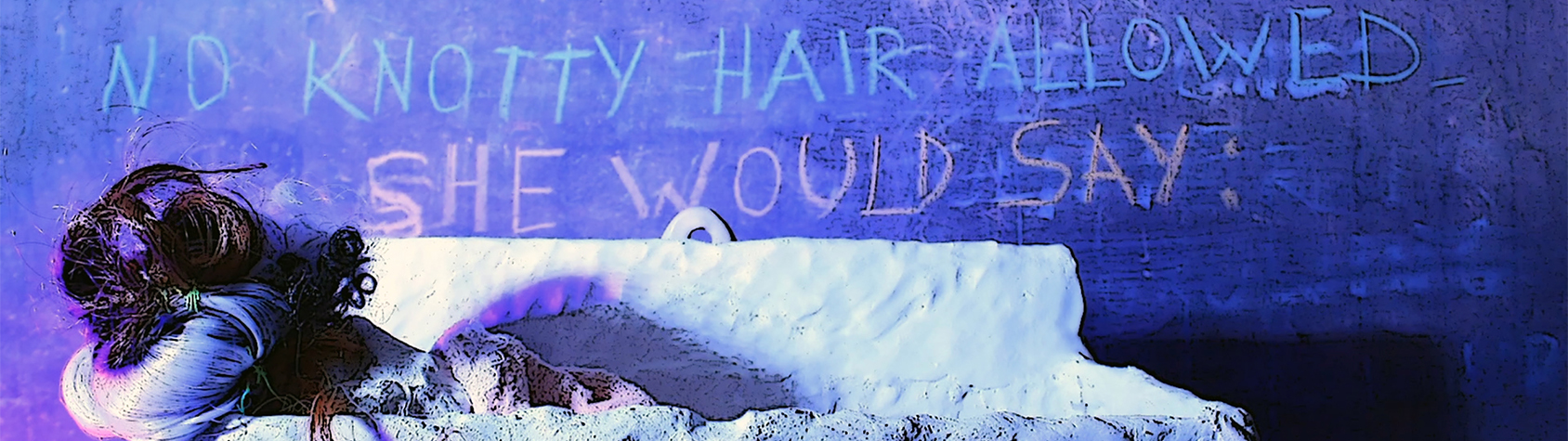

Snake skins and used condoms underneath our feet

Ruth is a collector of writings, a site dedicated to grey literature, unpublished and experimental texts, conceived by Manuela Pacella, born from the pleasure of writing and reading. We are very glad to host a text each month, selected from one of the sections of the four-headed Ruth: Yellow Dog, Hungry Ghosts, Free Spirits, Brain New.

This month we chose from Brain New A Tiny Town South of Rome by the visual artist and author Beatrice Scaccia who left Italy for New York more than 10 years ago and in this personal text reflects on the stereotypes and struggles of being an Italian artist in New York.

It was one cold November afternoon in New York. The light was murky, which is rare in the city. The lady arrived on time, leaving a driver waiting in a shiny car. She walked up the stairs accentuating her physical effort and her inexperience in entering ordinary buildings. While she introduced herself to me, I realized it wasn’t difficult to conceal my unease.

The whole situation was new: a collector requested to see my studio and my works. I had tea and Italian pastries to fill up the silence. She sat and grabbed a small fancy case from her handbag—that sparkling case contained her glasses. “Do you only work on paper?” She asked, gazing softly at my crowded walls. I nodded in response, smiling a little.

“It is clear you are Italian, I can perceive remains of a certain tradition in your lines.” When she said that, I felt like a needle entering my throat, and I thought: Here we go again. I could tell, in that precise moment, she had a specific, unmovable sense of the kind of Italian I was supposed to be. “Where in Italy are you from?”

“A tiny town south of Rome, but I lived in Rome most of my life.” I answered, almost chanting it. I have repeated those words so many times since I moved to New York—too many times. She smiled, sipped her tea and started chatting about Italy. Her hands were old but steady. The sky outside was getting darker. Long Island City was loud as usual.

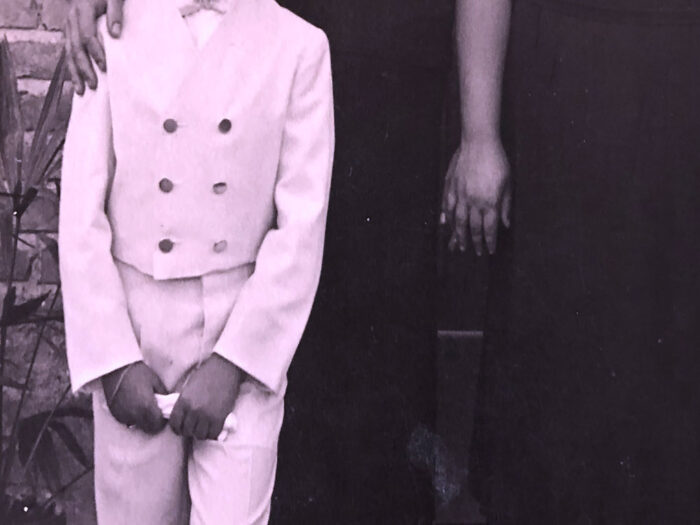

While her head filled up with her pleasant Italian memories, I saw my work fading on the walls. She craved expressing how incredibly beautiful Italy is, how delicious is the food, how impressive is its culture and history, and balanced lifestyle, and charming accent, and spaghetti alla Bolognese, and Sicilian cassata, and sailboats at dusk. Her hands in the air, mimicking beauty and excitement; my hands stuck between my tights withholding my lies.

That is not my Italy I should have said, that is not my Italy at all. My Italia has no culture, no beauty; it is a raw, uneducated place, that smells like animals and blood—where faces look alike, skins are impenetrable, eyes dramatic, and people complain about every little thing, refusing to grip any possibility of change. A place where being dishonest is a quality, where wanting too much is reprehensible, where contenting oneself it is almost a must. “What about the Roman Baroque? I can see the same kind of energy in your drawings…”

“Glad to hear you noticed that”, my mouth decided to say while my body adjusted its posture to the one I was supposed to carry. Cars honked in Queens Plaza. The old collector seemed bothered. “How do you feel in New York? Don’t you miss Rome? This neighborhood is so industrial and grey.”

“It is refreshing”, I said, “It was hard to be a contemporary artist in Rome, too much history.” She seemed to buy it, but it was just another lie. It was hard to be a woman there, a human being, a whole person. Besides, Rome is too close to my hometown, and my hometown casts its distorted shadows for miles around, blacking everything with a depressing, hopeless coat. And even in Rome, I kept being invaded by an abundant sense of heaviness and impotency.

I would notice women wearing cavernous, sad eyes, and men gathered around cafes nearly drooling at female-bodies passing by. Belonging to some group, some community, some family seemed necessary. Being authentic seemed impossible. I had to move away.

The old collector kept going on with a bunch of too-often-heard tales about summer trips on the Amalfi coast— the Mediterranean, the kindness of people, the medieval towns, Titian, Rafael, Leonardo. I pretended to participate in the conversation, still hoping at one point she would stop talking and buy at least one of my works. I am an impostor, my mind kept telling me. I am an impostor.

I should have told her the truth about my upbringing, I should have told her I grew up with nothing around, that the concept of visual art in my family was reduced to some plastic Madonna containing holy stinky water, and some crucifix.

My parents never visited Venice or Florence. I have been to Florence only a couple of times myself, and to Venice once. I didn’t have any pictorial cultural exposure until I was an adult. My only life vest, while growing up, were books. My experience was in books.

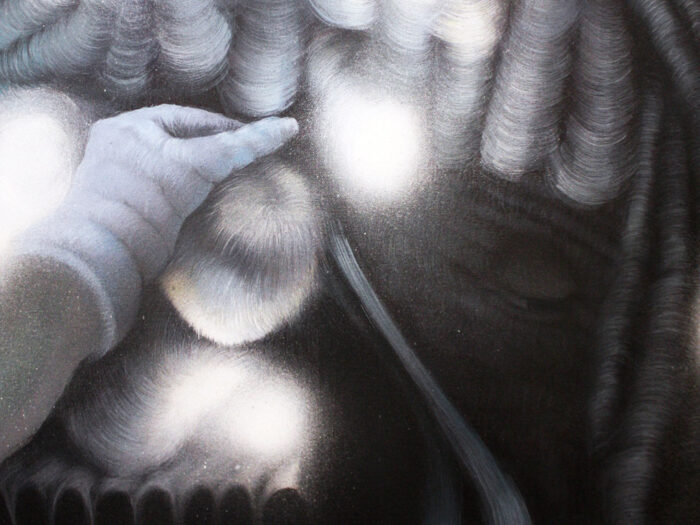

My grandma had a dark face, animal’s blood on her hands every other day, she would behave politely only around the priest. She would curse and smoke cigarettes one after the other.

Money was always a huge issue, but my grandma still managed to save up for some decorous hope-chest; part of it still rests in my closet, stiff like a corpse. We would make bread outside on Fridays, which could be perceived as a charming tale, but we had yellow polluted water coming out of our sinks, no heating system, no floors, no dreams. Cold beds, chickens with cut throats running around; bunnies I would get attached to being skinned before my eyes.

My dad grew up with no bathroom inside, no stoves. I remember dense green water and tiny little frogs in our basement. A surreal presence just below our stairs. “What about Positano? I was in awe for days over there.” I smiled and nodded again, like someone that has traveled around; while, in truth, I was not even sure about the exact geographical position of Positano.

My grandma had only one good suit in her closet. She would wear it for weddings and funerals. She got buried in it. It smelled like mothballs. A freeway cut open the land when I was eight years old; chilling, reckless cars would give me goosebumps driving by. No sidewalks to make us feel safe. My cousin and I, on the edge of the street, screaming at trucks and vans—snake skins and used condoms underneath our feet.

“I am going to Rome in a couple of weeks. Any suggestion?”

“Sure. You should totally go to see Padre Pozzo’s anamorphic ceiling in Sant’Ignazio”, I recommended to a now charmed lady collector. My act was well oiled. I could execute perfectly the flatten, shallow design of an Italian articulated, picky person. She wrote it down: Padre Pozzo, Sant’Ignazio. I kept going on about how that ceiling seemed to have been realized. Then, I moved to Caravaggio and Piazza Navona and the influence of Athanasius Kircher on Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

We were nine people under the same poor roof; nine uncomfortable creatures—two families and a grandma—forced to share tiny, unfinished rooms. The outside was beautiful, with a small stream, and oaks, and goats. But farmers would walk to the river to get rid of their garbage, and groups of stray dogs would terrify me and kill the goats. “Is your hometown nice?”

“Oh yes, it is a gorgeous little town with a cathedral. Did you hear the story of Steve Bannon trying to open a populist academy in a Mediaeval Abby? That is the area where I am from.” Her eyes got wide. She was hooked on the usual romance, on the trivial, reassuring version of the Italian people, on the flattery of the Roman Empire all around us, guiding us, reminding us of our glorious past.

After two hours, she was gone. I had a check for ten thousand dollars in my hands. A work to pack and ship—gone pastries, gone tea, gone act. I sat in my studio—eyes closed, loud city outside. I felt protected. Lies felt ok.

The shell that has been built around Italy’s darkest pearl is painful to wear. I’ve never needed to be reminded of my Country’s beauty, I need to forget its real nature, its provincial brain, its complaints and hypocrisy; its catholic skin, its sexism, its coward mothers and shameful secrets.

Plenty of men in my extended family died while middle-aged; many of them were naturally chauvinistic and violent—my dad passed away twenty years ago. Women keep surviving, respecting their husbands in incomprehensible ways. They bring flowers to their graves, every now and then, dressing like sad widows.

I opened the window in my studio to breathe LIC’s loudness. The sky was red—no stars, no greens, no sound of animals in the background. I missed it, I missed home. It didn’t make any sense at that moment, but I did miss it; the same way I would miss not having a mirror in my bathroom. After washing my face, I always need to look at it to realize I am still there, revealed.

I sat again in my studio and stared at my graceless hands. Past is always with us, even when quiescent.