A Past not yet Defined

In R. H. Quaytman’s practice each exhibition is a chapter of an open-ended oeuvre

R.H. Quaytman is one of the most outstanding contemporary American artists whose oeuvre can be seen as one of the most original attempts to revitalize and update the intellectual and emotional potential locked in the painting medium. The artist takes particular interest in examining painting in its physical—as an object that occupies a given space—as well as semantic dimension, as a symbol of a complex relationship with its meaning and material base. Quaytman enlivens the painting medium demonstrating its ability to remain an efficient tool in critical analysis of visual reality although the nature of paintings that are filling up this reality has radically changed in our times.

Since 2001 Quaytman oeuvre has been structured into “chapters”. Each of them is a separate exhibition consisting of paintings created especially for the exhibition and sometimes supplemented with carefully chosen earlier artworks. Each such exhibition is site-specific, meaning it refers to architectural but also historic and institutional context of a place. The exhibition at the Muzeum Sztuki was intended as an outcome of re-read chapters from 21 to 34. It was not meant to be a mechanical presentation of these chapters but a new story overarching them. As is the case with every exhibition of this artist, the framework of the story will be dictated by the context of the place which gives specific colors to the exhibition’s retrospective character.

In Quaytman’s biography, Łódź and Muzeum Sztuki are places linked with the very beginnings of her “book”. The first chapters were largely drawing from the material collected by the artist during her first trip to Łódź—the home city of some of her forebears. It was also here, where Quaytman discovered the oeuvre of Katarzyna Kobro, a radical constructivist sculptor who worked in this city between the 1920s and the 1950s and whose almost entire legacy can be found in the collection of the Muzeum Sztuki. Kobro’s art, in particular one of her sculptures, “Spatial Composition No. 2”, not only featured at some point as a frequent motif in Quaytman’s works but also provided the starting point for original considerations of the American artist on spatial dimension of image and painting.

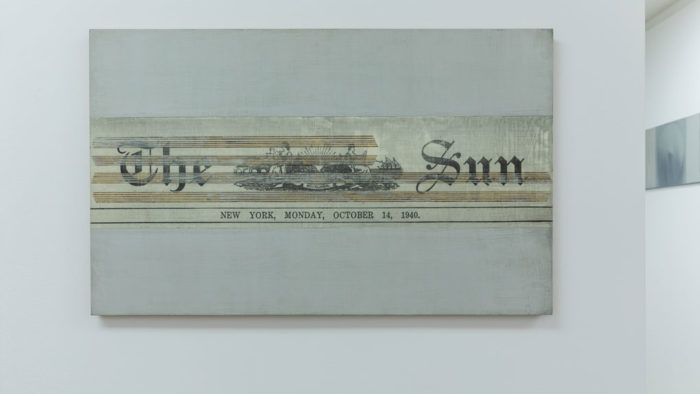

R. H. Quaytman, The Sun, Chapter 1, 2001-2002. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

“So it is. Once a book is fathomed, once it is known, and its meaning is fixed or established, it is dead. A book only lives while it has power to move us, and move us differently; so long as we find it different every time we read it.” The steady flow and constant instability of meaning are one of the key themes in Rebecca Howe Quaytman’s work. Her erudite archival investigations prove there is a certain plastic quality, a particular flexibility, immanent to both history in art and art history. Even though Quaytman highlights her paintings’ materiality and status as objects fixed in time and space, their interpretation is not at all stable and shifts with the works’ arrangements in the different locations.

The artist, a prolific commentator of her own work, refers to her oeuvre as an ongoing, unfinished book, with successive exhibitions serving as “chapters”, “units of meaning within a larger context.” Each of these consist of “paintings”—but the viewer should bear in mind that, in the context of Quaytman’s work, the word should be understood more as a verb than a noun. The technique applied by Quaytman does not indulge the usual set of fantasies that we associate with the medium—be it the closeness, the intimate connection between the artist and the work, the independent genius behind the creation, or the almost sentient existence we ascribe to painted objects.

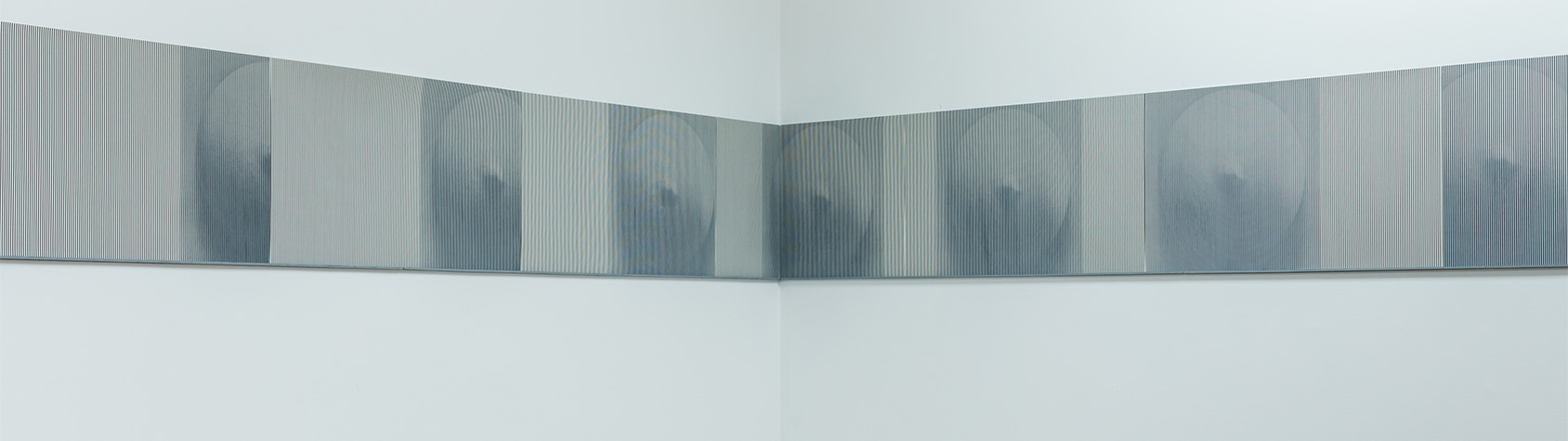

R. H. Quaytman, The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35 Installation view. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

R. H. Quaytman, The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35 [Warren], 2019. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

R. H. Quaytman, The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35, Installation view. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

Although rooted in a dense and mathematically rigorous set of rules, present within the works’ dimensions and their existence in space, the consistent use of a single technique with limited variations Quaytman’s chapters embrace individual interpretations. Such an approach echoes Rebecca Solnit’s views on writing about art: “There is a kind of counter-criticism that seeks to expand the work of art, by connecting it, opening up its meanings, inviting in the possibilities. (…) Not against interpretation, but against confinement, against the killing of the spirit. (…) This is a kind of criticism that does not pit the critic against the text, does not seek authority. It seeks instead to travel with the work and its ideas, invite it to blossom and invite others into a conversation that might have previously seemed impenetrable, to draw out relationships that might have been unseen and open doors that might have been locked. This is a kind of criticism that respects the essential mystery of a work of art, which is in part its beauty and its pleasure, both of which are irreducible and subjective.”

An association with Solnit, a writer, seems justifiable. Quaytman, a daughter of a poet and a painter, assumed many roles throughout her life and was able to look at the art and literary world from different perspectives. “Back then, my parents were two of the most opposite people you could imagine. As a result, I developed a kind of lenticular perspective—I was able to shift back and forth between their points of view. Probably my urge to make different kinds of paintings and put them together is related to that early experience”—she recalled in one interview. As a curator, gallerist and art historian, she contemplated the different facets of the art world’s knotty network. Quaytman’s recent exhibition in Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź may seem as a courageous step towards a disentanglement of relationships in which she had been submerged, and employing a calculated, rational manner in order to understand her present position and to separate ideas from identity.

This is not the first time that Quaytman juxtaposes current and earlier works in one presentation to investigate how the meaning of subsequent parts (or pages) changed over time and in confrontation with new spatial and historical contexts. But the exhibition offers a different look back, and a more complex return, heavy with histories of different scale. The city of Łódź and its museum, an institution established by artists—founders and members of the “a.r.” avant-garde group, among them Władysław Strzemiński and Katarzyna Kobro, serves as a beginning for Quaytman in many respects.

The Polish industrial city appears as the foreword to Quaytman’s open-ended book, whose chapters would later expand beyond a defined time frame and geography. Quaytman’s first connection with Łódź is her grandfather, Mark, born to a Jewish family. His portrait, like an image of an unusual patron saint, overlooks one of the rooms in the museum. His untimely death was evoked by Quaytman in her first series conceived as a chapter—The Sun, Chapter 1 in 2001. The title work, also presented in the show, depicts a newspaper clipping informing about her ancestor’s tragic death. The artist’s family history returns in the most recent chapter—The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35 in Muzeum Sztuki—as an eternal companion and a motionless, persistent influence.

R. H. Quaytman, The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35 [Strzemiński/Kobro], 2019.

Aside from familial lineage Quaytman explores artistic genealogies. One of them reverberates in a black-and-white composition representing an X-ray image of Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition. White on White from 1918 (The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35). The silkscreened radiograph reveals hesitation seeping through a carefully calculated composition. The doubt and indecision underlying the seemingly perfectly executed (but in fact, repeatedly repainted) non-figurative work, contradict the common belief in emotionless, pure abstraction. The affective and spiritual foundations of modernism are again summoned in references to Hilma af Klint (+ ×, Chapter 34) the heroine of Quaytman’s chapter that preceded to the one realized for Łódź.

R. H. Quaytman, The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35, Installation view. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

Yet, it is the founders of Łódź’s museum, in particular Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński, who emerge as Quaytman’s most prominent protagonists. The works of those two Polish artists were subjected by Quaytman to a number of alterations. The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35 includes depictions of Kobro’s sculptures and blown up details of Strzemiński’s canvases copied onto gessoed wood. Kobro’s influence is not only present in individual works, but permeates the whole concept behind the arrangement of the exhibition—her theory of art in space resonates with the way the works appear in Muzeum Sztuki: “The essential basis of sculpture is space and the manipulation of this space, the organization of the rhythm of proportions, and harmony of form, bound with space. (…) A sculpture should become an architectural issue, a laboratory experiment into ways of resolving space, into the organization of traffic, and urban planning that sees the city as a functional organism (…).”

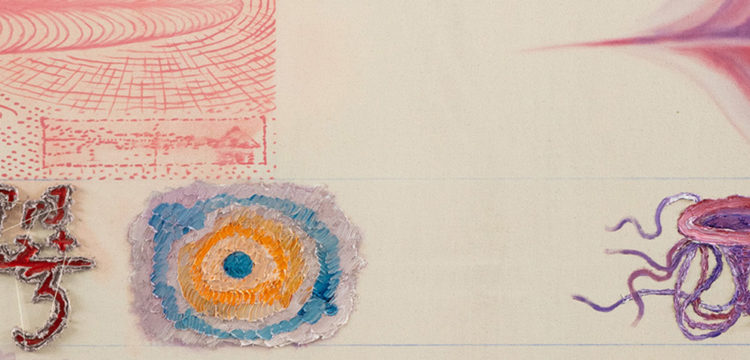

R. H. Quaytman, O Tópico, Chapter 27, 2014. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

R. H. Quaytman, The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35 [J. Zielinska], 2019. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

Quaytman looks both backwards and forward. The first work that the viewer will encounter in the show is O Tópico, Chapter 27 (2014), a square shaped wooden panel, with a high contrast op art pattern in the background and a black splotch of urethane foam emerging in the middle. The dark form conceals an eye, peeping at its onlooker through a small gap in the spume veil. This bodiless eye formally mimics the one portrayed in the neighboring חקק, Chapter 29 (2015), a work containing a visual quote from Paul Klee’s monoprint Angelus Novus. As though mirroring the complex journey of the work by Klee through the minds and writings of Walter Benjamin, Georges Bataille, Theodor Adorno, Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem, the both god- and humanlike creature in Quaytman’s painting was repeatedly distorted through thermographic investigation into its history.

R. H. Quaytman, Chapter 29, 2015 חקק. Photo HaWa. Courtesy Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

The realization that the eye in O Tópico belongs to the Angelus Novus brings to mind Benjamin’s famous comment: His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The show in Łódź is a tribute to the past and a the many ways to make sense of it. In Muzeum Sztuki, it is us who the seraph watches. With the angel’s gaze on our backs we will continue through the exhibition until to discover hints pointing towards the protagonists of Quaytman’s next inquiry—Marcel Broodthaers and René Magritte. It seems that in Chapter 36, everything will change except the rules.