A Meeting of Beaming Lines

Body practice as drawing through the work of Emma Kunz

Emma Kunz (1892-1963) was a healer and researcher, who is being now widely recognized for the artistic qualities of her drawings. In her radiesthetic and clairvoyant work she advised and healed her patients in profound ways. In 1941, Kunz discovered the power of the Würenlos healing rock that she named AION A. The Emma Kunz Center is situated at the source of AIONA A and was founded by Anton C. Meier (1936-2017) who was healed by Kunz from paralysis. The center preserves the archive of Emma Kunz research and body of work.

This essay was written thanks to the generous exchange with Bettina Kaufman and the Emma Kunz foundation, and with the support of CBK Rotterdam.

Drawing is a messenger. Since we draw mostly with our hands, we create from that tactile connection that brings our insides outside. Drawn lines are a note of our living, of breathing and being breathed. While drawing, we look at our hands moving, and we move those hands from impulses of our physical and mental body. But our multifaceted bodies are also perpetually connected to other elements that bring us towards drawing. We are placed in a space that is situated in present, past and future time, and in those spaces are everyday things, but also memories, cultural notions of racial, sexist and capitalist oppression, dreams, energies, etc. There is a lot we cannot see with our eyes only, but rather sense and feel. Drawing can be a means to depict things we perceive but not see, and by looking at drawings we receive more than just plain conscious or rational information.

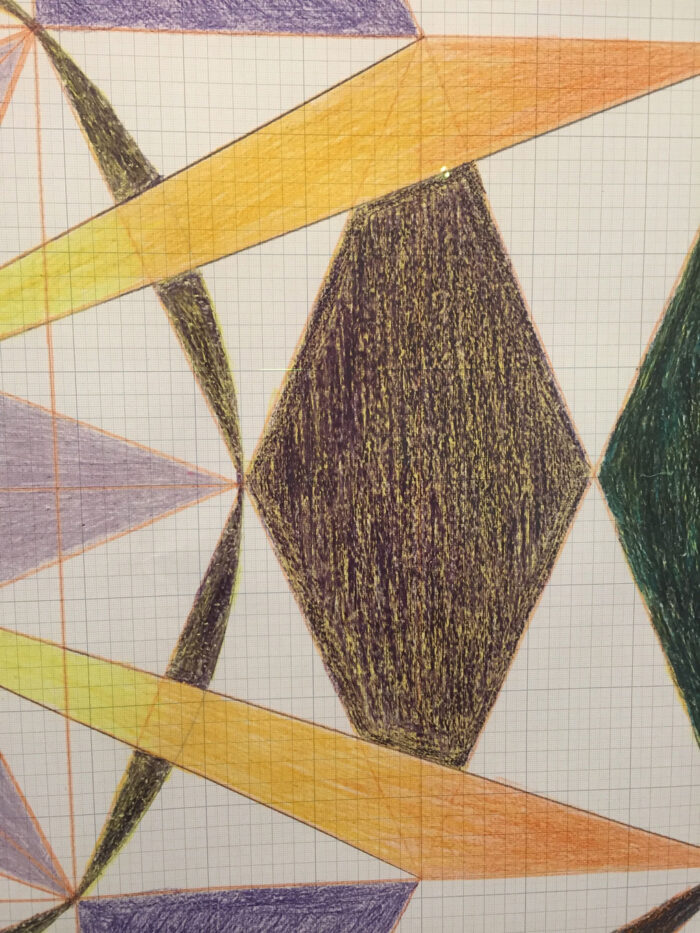

The drawings of the healer Emma Kunz depict geometrical force fields that came into her mind and body and through her hands, because she was able to be in touch with earthly energy that is all around us. In her practice as a healer, Kunz used drawing as a tool. Her stunning drawings on graph paper are now often shown in an art context but they are no artworks. Drawing was a mediation through which she could ask questions and get answers that she presented to her patients to understand their ailments and heal them through earthly energy fields. Kunz used to hang the drawings in layers on the walls of her therapy room. By picking one and showing it to her clients she could explain how their bodies were connected to the world and that which moves them. Kunz might have made a drawing for a specific moment or question, but she could also re-use them at times. Her drawings have a universal quality and hold several meanings together on one sheet of paper.

During the Victorian Age, to give meaning to the short life expectancy, Western spiritualism drew its rituals and set of beliefs on native knowledges and paganism. Spiritualists believed communication with ghosts and non-human energies possible, and that the insights of higher evolved spirits would offer help within ethical and moral dilemmas. Spiritualism isn’t defined by a clear-cut set of rules, there are hardly any strict guidelines. In its essence it is irrational, undefined and anarchic. Many spiritualists were abolitionists, not only seeking recognition for their work but also actively rallying for women’s rights and supporting the abolition of slavery. Medium artists from that time were almost all women. They lead a non-conformist life: they were unmarried, earned their own living, and defined as being beyond the visible rational plane of existence. The spiritual artworks made then were radical and abstract, and preceded Modernist abstraction—as set down by the Western canon of art history. Hilma af Klint and Georginia Houghton are two other examples famous for their profound works preceding their times. Born in 1892, Emma Kunz discovered her clairvoyant and radiesthetic skills when she was around 18 years old. Kunz left the trail that society paved out for women during her life-time, her work and story is one of feminist non-normative making. She lived together with her mother first, then her sisters and eventually by herself. She earned her own living by working in a factory for knitting yarn, as a housekeeper, and ultimately as a healer. When Kunz started to make large-scale drawings from the age of 46 on, she asked her friends to call her Penta. Kunz first made drawings with a pendulum to identify points from which a shape was created. Eventually she switched to tracing points and lines without it.

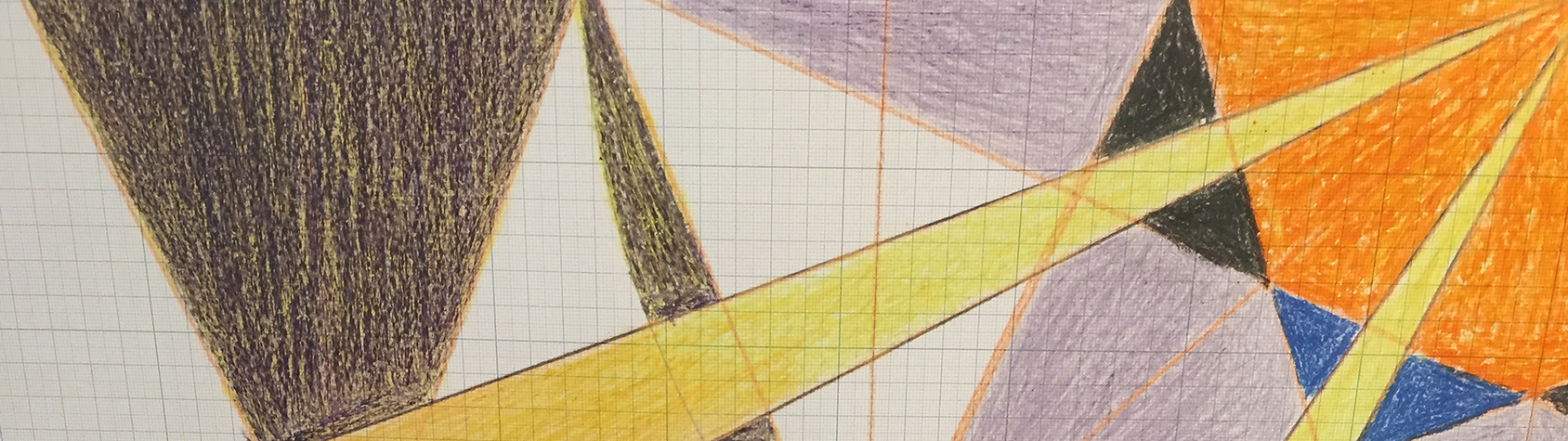

After a long pandemic-induced hiatus on moving into the world, I traveled to the Emma Kunz Center in Würenlos, CH, this summer. Welcomed by Bettina Kaufman, the director of the Emma Kunz foundation, I hoped to understand better what her complex compositions were transmitting when encountering them. While her work is becoming increasingly more researched, it is not quite possible to reveal as much as I had hoped for. Apart from the brief and rather dense essay inside her self-published small book Die neuartige Zeichnungsmethode (The new drawing method), Kunz hardly disclosed her ideas in notes or sketches, and what we know now was learned mostly from eyewitnesses. Kunz only ever explained the drawings orally during her sessions with her patients. After arriving, Kaufmann opened the closed museum for me and we walked together through the exhibition. I noticed that my heart started to beat faster and my breathing got deeper. I felt like I was going in and out the drawings, as if my heavy breathing would pull me towards and away. My nervous system responded to the excitement to finally see the drawings in front of me, to understand their size and impact differently as well as the details that get lost in reproductions. But the pattern of breathing was also triggered by the drawings themselves as they slightly pulsate. The lines field seemed to move and expand, and I felt their vibration resonate in my body. Many of the drawings are tightly drawn, layers of geometric shapes, intertwined lines form images that look like mandalas. I was surprised with some of the more roughly drawn works which I hadn’t noticed before from reproductions. I loved to see irregularities, gummed out lines, or their endpoints that went beyond the created shape. Like a little error that told me that a person had made this, that these seemingly pure shapes were still porous and alive.

I spent three days in the Emma Kunz Museum, just sitting with the drawings, slowly getting to know the ones on view inside the museum. This has been the longest I have ever looked at someone’s work ever. The exhibition was frequented by other visitors but I was often alone with the drawings. I would get up and stretch, especially my neck, rotating my left shoulder that often hurts deep inside. I’d walk around, sit down again and take some notes. My mind wandered—I felt curious, melancholic, bored, content, and restless. Like with breathing in meditations, I needed to bring myself back to the drawings frequently. I took photos of drawings mirrored in the glass of another frame, and tried to find all those details that were irregular or unexpected. I felt an immediate reaction in my body when I first saw the drawings but after a while it diminished. Eventually it seemed like the highly structured geometry increased its shield. Some of the drawings didn’t reach me inside because the measured and controlled composition appeared like a far away cosmos I wasn’t invited into. Thinking of Kunz’ praxis, the drawings didn’t exist then in a vacuum like a museum, but along her as a guide and communicator. In the museum, framed and hung next to each other, the drawings seemed to have lost some of this dynamic affect.

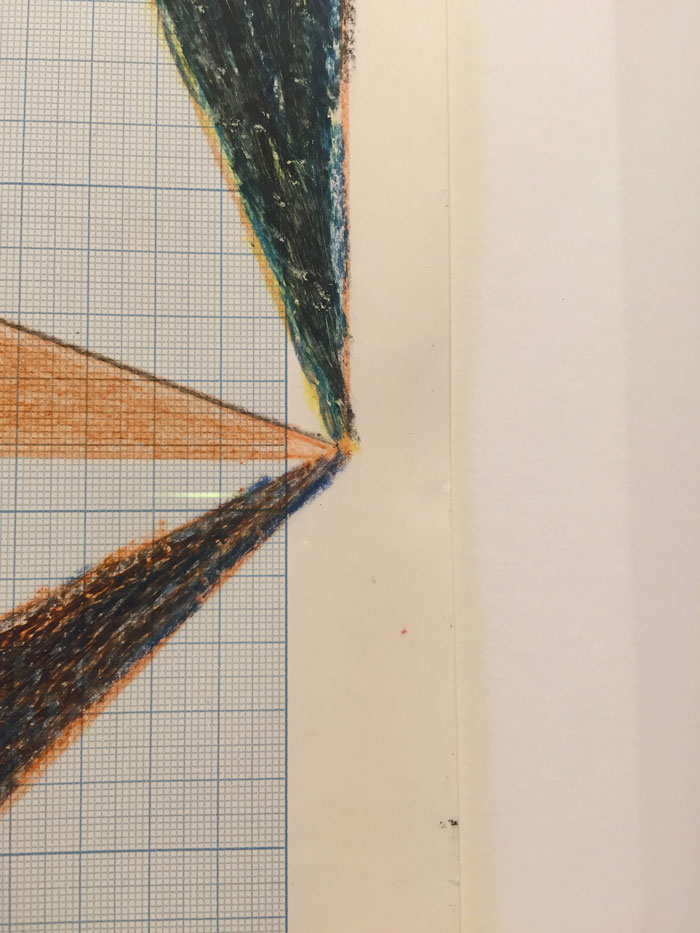

I was drawn to one work in particular, and the seduction it radiated told me that it was most related to what I was seeking. Thick and coarse color patches were part of the larger geometrical shape. It appeared like a scaled up detail of other drawings it was surrounded by. This one depicted the most simple shape, but it featured more details on different surfaces and color applications. It feedbacked the detailed and precise drawings by posing something quite different. My chest encountered a release there. My exhale extended and got longer, because it resonated in all of my limbs that there was more space to put myself in. The lines were drawn thickly with color pencil instead of the fine line of a pointy pencil like with many of the others, and the color was applied more dense and layered. Observing two layers, one color shone through a top layer of rugged lines. The surface appeared to flicker. The layers of color were orange and blue, yellow and green, yellow and purple, yellow and blue, and purple alone. By having the two layers of colored lines mix on top of each other a new appearance was created when looking at it from a distance. This told me of an under-presence, of something veiled that makes itself noticeable. However when getting closer you see that the personality in these parts is coming mostly from yellow as its base color. The out-lines of the shapes were drawn with the colors that also filled in the color fields which softens the border from drawing to paper. I corrected my notes a day later: it frees the boundaries. The elongated triangle shapes that enclosed the colored field were a gradient from orange to yellow. While the whole drawings appeared dark in tone, it is yellow in all parts that support the shape. There were eight triangles like that and they met in the center, as if they were focusing all their energy together in there. With all the drawings on display, I noticed a center (except for one). They had a point in the middle of the paper from which the image developed and returned back to. The drawings appeared that way like an origin story of creation. After some time I felt an itch, like the spaciousness I felt began to contain movement. There was an urgency in my fingertips to continue this drawing. To relate to it by joining into the process. With my mind and body I filled in more paper, more surface, so that it became less of a centralized object but would be embedded and held by what was around it. I felt the desire going from my chest through the single symbol, to merge itself into its ground.

Physically and mentally attending to the signals being sent out from the past, I encountered myself in the present moment. The lack of information into Kunz’ process tells us that she didn’t want or need us to know her own interpretation of the drawings. It was simply not that important to archive their meaning in words. The knowledge I was looking for was inside the lines, what they vibrate, and how my body receives that. The key is not just knowing the methods of Emma Kunz, but also knowing my own body and its responses. To look at the drawings felt like a spiritualist practice of trusting what is undefined, and attending to what you receive from that.