A Desert Of Water

Part 1 – The infinite night when the flood devoured the drought and the mud faded our future

Between May 2nd and 17th 2023, Emilia-Romagna was hit by a series of events that generated flooding and landslides in 44 municipalities, mainly in the provinces of Ravenna, Forlì-Cesena, and Bologna. The heavy rainfall, that fell in 48 hours almost in the same quantities as in a full year, caused 23 rivers to overflow and a thousand disruptions and landslides. Fifteen people died and almost 30,000 have been displaced and evacuated. The damage was estimated at around 9 billion. The government allocated 2,5 billion, while several weeks after the event an emergency commissioner with no connection to the territory has been appointed with serious delay during the reconstruction phase. So far, the funds have not reached either the local administrations or the affected inhabitants yet.

The flooding has been described as one of the greatest climatic disasters of recent decades in Italy; in a region that suffers severe drought periods due to high soil consumption, the effects of intensive agriculture and livestock farming, along with cementification, have progressively limited the land’s capacity to absorb water and rivers’ flow.

About four months later, this story—that was written right after the events—tells the direct experience of the flood that affected my hometown, our homes, my family and friendships, and all the inhabitants who are still struggling to survive, in the name of climate justice and against the effects of global development. The intention is not to become invisible, fuelling debate and action towards the future, starting with sharing our trauma and emotions as a community affected by the environmental disaster.

This is the first of two chapters, the next one will follow next week.

“Faenza is flooding again. In Via Lapi people have climbed on their rooftops. The flood has reached the city center, Corso Garibaldi and Corso Saffi are already beneath, and the water is heading to Piazza del Popolo. Our building has no electricity”. 9:53pm, May 16th, my sister texted me.

“Here in Castelbolognese the water is coming up from the riverside road, from Via Biancanigo. I can see it from the window.” 12:05am , May 17th, my mother says.

“All the streets nearby the river, ours included, are flooding, we’re going upstairs. Grandma has stayed down” 12:34am.

“We are completely flooded; the river comes into the house through the garages and the cellars.” 01:27am.

Then silence until 6am, when my sister sends a photo of our house portrayed by the neighbor. The small driveway, the garden, the street, the cars are one thing. Their features are murky and only briefly noticeable: some leaves, the cars’ roofs, some branches, and other unidentified floating objects, enveloped in muddy water, it all almost reaches my Grandma’s balcony.

On the night between May 16th and 17th nobody slept. Surely not in my hometown, where I was born and grew up, between Castelbolognese and Faenza, in the province of Ravenna. Certainly not even those of us who were far from there, and kept obsessively looking for news on Facebook, among the few neighbors to confirm that my and their family was fine. When the water did flood our village, it was only two weeks after its arrival, on May 3rd, 2023. A phenomenon that in the past only occurred every fifty to one hundred years.

The first time it was thirty centimeters of water, overflowing somewhere on the Senio stream where the river runs along the town center and the countryside. My grandmother, who is 95 years old, remembered this type of water in the past, when in certain precise stretches—before the embankments were recently rebuilt—the stream used to overflow and flood the fields. The farming community knew how to deal with it, taking refuge and organizing themselves to take advantage of the flood, which used to be considered as a proper resource. People here had an unspoken relationship with the river. Now my grandmother can no longer recognize it, nor do the inhabitants of our village.

On 16 May 2023, the Senio floods in five places. The water first overlooks the road, making its way slowly. Then it advances through the countryside, and at this point it is fast, swirling and angry with a scream that slams windows and knocks doors down. If the inhabitants were expecting only a few centimeters, now it’s almost two meters. No one could have imagined it, as the strategy to rescue belongings and homes considered only small useless gestures such as sandbags, pallets, wooden planks; an effort rendered ridiculous by the breaking of the banks and the rising of the asphalt.

In the darkness of a town that has lost its access to electricity, my mother keeps an eye on the stream through a lamp above the neighbors’ garage, while dad watches it rise up the stairs. There are definite visual limits that govern their sense of survival and danger. One of them was that lamp, the other was the last step of grandma’s house, downstairs.

It is impossible to recognize the familiar landmarks of anybody’s place, now all distorted by the flood. The road, the fields, the neighbors’ yards gleam with the water that has eaten them away. The only artificial lights of reference are those of the cars, continuously switching on and off, as if there was someone inside, until the phantoms of the river leave them to shipwreck peacefully in the current. At 4 a.m. when the water stops rising, the noise has disappeared and silence creeps in like a deception. A dark, spectral magma lingers over two meters of life and work built up in years. My parents observed these two meters unopposed to the point of torment. They fell asleep and woke up still seated, sleeping an hour in a night that exchanged the day for mud. How much loss is down there? What can be saved? Certainly not the countryside, the plants, the animals, the things in the streets and those imprisoned in cellars, garages, houses.

Do we still want to improperly speak of bad luck? Like living on the ground floor, or not having an alternative. Our neighbor drowned in the flood while he was still talking to the other inhabitants to get some courage, as the furniture floated around him, at a height quickly exceeding his own. What has changed in the way we live, build and feel safe in our homes to turn them from shelters into traps? Why are we consciously steering the climate towards scenarios of death?

Some friends in the worst-hit areas of Faenza had water up to their roofs, dripping from the sky and ceilings, and they had to climb up to avoid drowning, with children on their shoulders. In the dark, with their livid faces lit by mobile phones and with water up to their chests, they shouted in the hope that someone would hear them, not knowing if they would stay alive.

This is the moment when time suddenly accelerates, only to stop in the doldrums, and nothing that seems to be over really ends. The rush of water is replaced by its innocent retreat, in a murky calm that erodes, swells, and then spits. The houses in the village have been emptied of their inhabitants, more will soon be vacated because they are no longer safe to live in, and will be hauntings like the memories and the mortgages that accompany them. The foundations begin to bloom with molds and fungus, the walls crack along the hanging frames and bedheads. Streets and cellars smell like damp and slip mixed with slime.

In the early hours of the day after we weren’t really able to do anything. Like us, many people lived with the mud for hours. We looked at objects inside our homes without knowing how to move them. Where does one begin to throw away one’s living and affective space? Where does one find the space for the hope of saving something? Better not to open any door, touching the lowest point of one’s dignity, wandering aimlessly in a perturbing space. Peeking through the folded door and from the top of the stairs we glimpsed our bruised and randomly redistributed world: the leg of a table now stood over a window, the couch had climbed onto the table, the door swung over the bookcase, and from an indistinct pile peeked papers, clothes, memories. All the things on the highest shelves marked the water’s edge with a thick brown line still dripping. This image was a photograph of a disfigured everyday life, which had drowned and then floated for days. Nothing had been spared, in a kind of solidarity between the elements, all subjects of the simple principle of water, which had molded them according to its rules, so that each thing could reflect another.

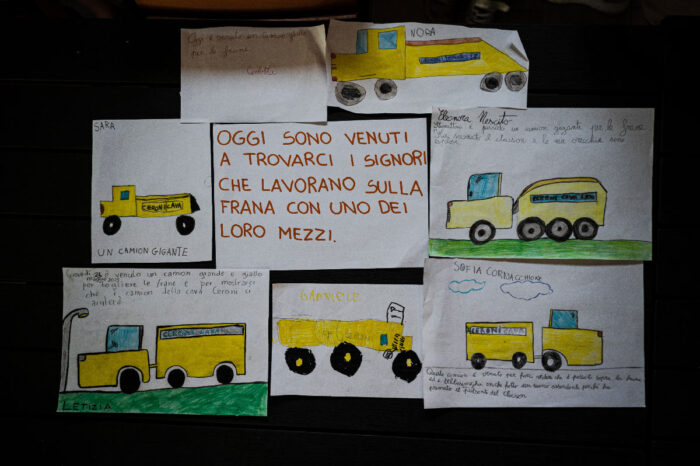

In the midst of this stagnation, however, a great deal of work with shovels, spades, brooms, rubber boots, hydro-cleaners came into being. A new flood-related vocabulary was introduced through the arms, faces, and great energy of the civil society that quickly organized itself to help. Volunteers from neighboring towns came to our village by the hundreds, referred to as the angeli del fango (mud angels), or la meglio gioventù ( the best youth). There was actually nothing angelic about them, on the contrary, this is a classic mediatic political rhetoric that recognizes activism out of something that shows up in the right place at the right time, and fights it as it acts through conflict, opposing the current denialist policies of the government.

These activists did not ask for any recognition of their efforts, as they were fully aware that there is nothing heroic about witnessing an environmental disaster, on the contrary it brings along a collective trauma we’ll all have to heal from. This supportive community has lent us vital help to survive, perhaps even without realizing it, by opening doors that would otherwise be blocked, tipping the precarious balance a hallucinated hope rested on.

There was much practicality in throwing, washing, moving and cleaning everything. It had to be done quickly, preventing the houses immediately from rotting and places infected. A trauma that is repeated every time someone asks us—“Do you want to keep it?” —“Yes, I do.”—“But wait, take a good look. It’s impossible for this thing to be saved, maybe it’s better to forget about it and throw it away.”—“OK.”

The street slowly began to become the household. Suddenly everything was living there, and what had previously made our intimacy consistent was now being handled, denuded and thrown into the sight of the bulldozers loading quintals of objects and making them disappear as quickly as possible. Our memory contributed to an unusual urban cemetery, faded and leveled horizontally in a brown magma. Everything had the same stature, there was no longer an upright thing, standing in its usual position. The material of which the objects were made had dissolved and was beginning to wear away from within, as if it had been abandoned to the elements for years, without any care. We could not recognize what to throw away and what to keep, because the mix of water and mud has this power to erase.

In the courtyard, one could see the neighbor’s wedding photos hanging like clothes, or the collection of old record players, stereos, typewriters, which—unbeknownst to many—dad collected for our village’s future electronics museum, as a collective memory. For days my father chased after them and tried to save them by rummaging through the piles, along with personal belongings whose shape he vaguely recognized. He would find my uncle’s childhood objects, his handwriting or photos of my grandmother. He would stubbornly try to clean his electronic equipment, his tools from the work in the factory and in the fields. They would slip off his hands, oxidized and corroded by the mud. Mum’s painted ceramics, a photograph or a letter now had the same shape as a sofa, a washing machine, a shelf, or what we could buy back.

Now our memory and our affections had turn into waste. My sister and I lost family memories that had been passed down through generations via objects, utensils, trivial—what we could call “useless”—objects, which now had the same value of a fossil coming from a future we were unable to protect. A similar fate befell public archives, municipal libraries, museum collections and craft workshops that lay half-buried, hidden from our view. As if we had bowed to an order of importance to save primarily what is visible. Months later, many of these archives have yet to be cleaned and recovered, with a great loss we will never be able to quantify.

Outside the cities, the countryside and hillsides are still trying to survive. Trees and plants are still alive and breathing, although deeply wounded in an agony, as their leaves are yellowed by the mud’s asphyxia and attacked by fungal infections. The earth no longer belongs to them, a hard compacted fissure prohibits oxygen and strangles the vegetation in an endless grip. Those who managed to survive the violence of the water now have to try to coexist with the mud. Many trees are gutted, amputated and still rooted to the ground. The dense network of roots that weaved through to protect the mountains and riverbanks is no more. A network through which plants communicate, feed and reproduce, creating a vegetal community.

Like in other regions, large-scale deforestation in Emilia Romagna has begun to make way for building or cultivated land. Forests have been used for land consumption. The riverbeds have been reduced, so have the embankments, to make way for intensive agriculture and livestock farming, or worse, concrete. When this happens, the water flowing in the rivers increases its speed, corroding and consuming. Severe dry spells in summer and winter leave trees in the riverbeds to grow, while intense and violent rainfall in spring and autumn fills them with rainfall that falls in 48 hours as heavy as in a year. Twentythree rivers and streams flooded all at once in two days, when the drought emergency was still ongoing, and it is still ongoing. There is a desert overflowing with water in Emilia Romagna. There is an impermeable land, compacted under the effect of intensive agriculture and cement, a land that is incapable of drinking. There is an abandonment of homes and land because they are gutted and collapsed, submerged and then faded under the mud. It is estimated that 42% of the utilized agricultural area has been affected by the flood. There are almost 21,000 farms in the affected area, 49% of the entire region, more than 29% in municipalities with flooding and 19% in municipalities with landslides. [1]

The villages of the Tuscan-Romagna Apennines such as Casola Valsenio, Brisighella, Palazzuolo sul Senio, Marradi, Modigliana, and Tredozio are rundown by landslides, and have long remained isolated. In these places, the symbiosis and bond between humans, cultivated land and plants is very tight. One works alongside the other. Chestnuts, olive trees, beeches, firs, conifers; large patches of vegetation began to move, eating away roads and houses. The mountain walked downhill, as if it were made of nothing, inconsistent.

The trunks of the chestnut trees were breaking with a deafening noise of wood, branches, leaves, interrupting their centuries-old silence. Some chestnut and olive trees were a hundred years old, carrying with them a piece of historical memory of territories that remained tied to agriculture and rural life. Those who practiced an economy linked to these trees abandoned their places of origin. The time to regrow them cannot be bought. We are in the presence of a suddenly absent forest memory, and the same thing applies to wild animals, and even more severely to farmed animals. The impact of the landslides has been so violent that many animals appear as if they are embalmed. They seem to be alive, but on closer inspection they remain motionless, not breathing, not moving, they have died surprised by an unspeakable force, which has imprinted them in the same position they were only a few seconds before.

It is a collective funeral, we tell ourselves. And we celebrated it with much love, because there is a deep and historical peasant attachment to these areas, especially in the small villages. The Friday of the traditional feast of Pentecost in Castelbolognese, on May 26th, was transformed into a collective ritual of wine and tears, accompanied by the ringing of bells, for anyone who wanted to be heard. We walked through the village until sunrise, convinced that going to sleep would remove us from a ritual we recognized ourselves in as a fragile desiring community. Hugs and hands to the sky were occupying a Via Emilia closed to traffic, made available for us who walked lovingly along, still getting dirty among the piles of things to be thrown away by shops. A world that is no longer for sale, all matter is no longer of any value. Much like our flooded homes and our lives, exposed to an 87% flood risk in the province of Ravenna, and with 14.6% of the regional territory classified as very high hazard for landslides. [2]

When the idea of a future is taken away from an entire community and its homes, the banality of rain begins to have a different sound. This sound is the symptom of a trauma that repeats itself endlessly, without finding peace. It is manifested in the lingering smell of mud and mold, like a memory that resides in the future—like missing one’s home while it is still there. The data marking this future was published decades ago, advising against the construction of houses near river areas in the province of Ravenna, as well as the design of basements, cellars, and subways. To date, in the Emilia-Romagna Region the legislation on soil consumption is totally inadequate to mitigate the deadly consequences of landslides and floods.

So why do we continue to build in a floodplain? Why are sacrificial territories being used to live and produce, instead of making room for rivers, streams and mountains? Why hasn’t the state implemented their plan against hydrogeological instability? Why haven’t expansion reservoirs been built? Why haven’t more powers been given to the basin authority over corporate and political interests, and a ministry against the climate crisis set up with its own, permanent funds and prevention and maintenance strategies? In Ravenna, the course of the canal was diverted in 24 hours to save the historic center and its Byzantine mosaics , choosing to sacrifice the countryside. An ingenious work that spared the works of art before the territories, attributing a non-negotiable value to our historical and artistic heritage. What if we were protected with equal care?

[1] Emilia-Romagna Region, Agriculture: initial estimates. Communiqué of 25/05/23

[2] 2021 ISPRA report on hydrogeological instability in Italy