A Demand, A Pause

In conversation with Baptiste Cazaux

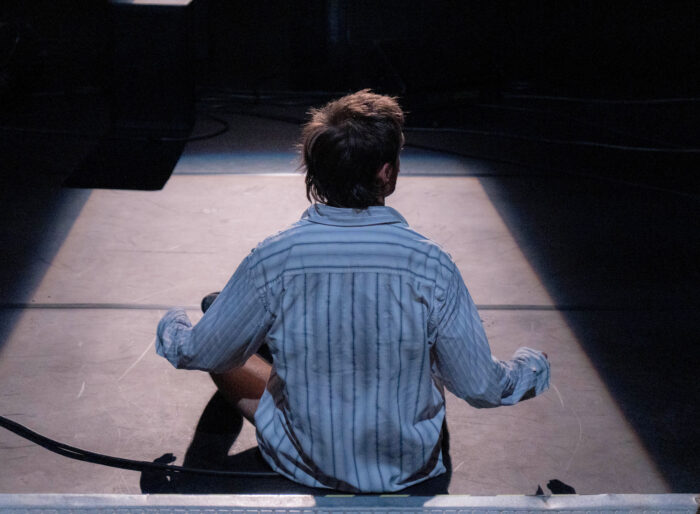

The city gymnasium has been transformed into the stage for the performance. Dim lights trace the edges of the scene, now occupied by six sound speakers scattered around; some pointed towards the ceiling, some leaning on the floor, others facing the audience. They are silent, yet poised to resonate. It’s mid-July, and the atmosphere is dense, warm and sweaty, charged with expectations. The performer is sitting in the stands, looking back at the audience, on the four sides of the stage. In this enduring waiting, the scene opens.

With their latest performance piece titled GIMME A BREAK!!!, the French dancer, performer, and choreographer Baptiste Cazaux presents a work that moves forward their exploration of emotional peace and detachment in the face of capitalism. In a duet with the loudspeakers, they compose a deregulated space-time filled with complexity and contradiction, seeking a vital impulse. The piece draws deeply from the young Swiss performer’s personal experience with depression during recent lockdowns—a period when music and DJ practice became central to their life, allowing them to experience intense emotions and sustain their creative process.

The performance was presented within the 54th edition of the Santarcangelo Festival which, under the title “while we are here”, was directed for the third year by Polish curator, dramaturg and critic Tomasz Kirenczuk.

The following conversation between Baptiste Cazaux, Federica Nicastro, and Chiara Pagano delves deeper into some of the themes explored in this work.

Federica Nicastro: Your last performance, GIMME A BREAK!!! (2023), was presented at the Santarcangelo Festival and has been touring throughout 2023/24. It’s your third personal, choreographed piece. Before delving deeper into it, I would like to know more about the genealogy of your practice from dance to a more performative realm.

Baptiste Cazaux: I started dancing when I was twelve, focusing primarily on ballet. After graduating from high school, I went to a dance school in Geneva. There, I learned how to dance, but I always felt I didn’t have room to be creative, even though I chose this path because I wanted a medium to express myself, somehow.

After that path, I started working as a dancer for different choreographers in Switzerland and Belgium. In 2019 I created my first piece EXERCICE DE STYLES #2, based on the idea of spontaneous writing and composition: the short improvised choreographic section, provided at the beginning of the performance, would transform into a back-and-forth game between me and my colleague Akané Nussbaum.

Shortly after COVID-19 happened, I created a second work called perfect pitch, with my friend Nelson Schaub (aka Être Peintre), who also signs the music of GIMME A BREAK!!!. perfect pitch (2021) was based on the idea of amateurism and academic dance practices, as well as the concept of failure, rendered through the use of autotune. It was about the idea of perfection, and how the inability to achieve it can also inspire and generate movement.

Chiara Pagano: What you say about failure and perfection makes me consider GIMME A BREAK!!! as a spontaneous continuation of your previous investigations, so I wonder if the title, in its assertiveness, sounds like a stand against the capitalist “presumption” of bearing the unbearable?

Baptiste Cazaux: GIMME A BREAK!!! is actually a play on words. It’s like: “leave me the fuck alone, I need a break, I need time for myself, I need to chill”, while also referencing drum breaks, which are very present in the piece. The Amen break is an emblematic drum sample of rave music, specifically jungle and drum and bass. The title is written in capital letters with three exclamation marks to emphasize its dual meaning—as both a shout and a demand.

Federica Nicastro: This makes me think of the work’s reference to the experience of confinement and solitude—specifically after isolation during the pandemic. How is it linked to this specific moment of your life?

Baptiste Cazaux: Yes, the piece comes from a moment of depression I went through, during the pandemic confinement. It was a time when we all, in a sense, had to take a forced break. I kind of lost my mind and wanted to question that moment in my life, contextualizing it within a broader perspective through this piece. I was trying to find ways to feel good while I was feeling bad. I think this state kept lingering with me for a long time afterwards and creating this work was a way to purge it from my system. That’s how I came up with it. I also appreciate how this work can speak to anyone—being somehow a shared experience in everyone’s life.

Chiara Pagano: The idea of “losing one’s mind” carries the images of the headbanging practice, at the core of your performance. This movement, often associated with musical genres like heavy metal, punk, and dubstep, also parallels rhythmic practices in Sufi mystical rituals, where it functions as a form of meditation and spiritual remembrance. Your work highlights this duality: headbanging as both a meditative act, and a source of physical exhaustion when taken to the extreme. How did you pick this specific movement, and what significance does it hold for you?

Baptiste Cazaux: During a residency in Geneva called L’Abri, I created a 15-minute performance titled meditation on pretty fast music which became my entry point for this research. I’ve always had a strong connection with music, but it deepened significantly by then. At that time I was practicing a lot of meditation, like YouTube meditation, to calm myself down, and started DJing.

I wanted to work with the idea of finding catharsis. For the performance I recorded myself speaking as if it was one of the meditation videos I used to watch, interrupting it with a hardcore dance moment—this is because I’m interested in the paradox of finding peace in something that is rough, violent, fast, and direct.

With GIMME A BREAK!!! I wanted to create a meditative practice for myself. I came up with the headbanging because it’s something very intuitive to me—whether it’s just a soft nod, I often do it whilst listening to music. It’s my primal reaction. I began using the Amen break as a mantra to get a rhythmical constancy, a tempo through repetition that leads me into a trance-like state. Headbanging is a movement linked to the pleasure of music, yet, through repetition, it might become exhausting, dangerous and painful.

Chiara Pagano: How do you reconcile with your desire for something that is both pleasurable and dangerous? Isn’t it painful to headbang for so long?

Baptiste Cazaux: Actually, it is really painful. Before starting to work on the piece, I was doing a one-week residency. On the first day, I thought, “OK, let’s headbang!” But the result was that for the next three days, I couldn’t work anymore. So, I decided to find strategies to take better care of my body. Now, I have massage tools, I stretch, and work out.

I began to question the connection between pain and pleasure, asking myself: “Where does this pain come from? How is it tied to pleasure?”

Chiara Pagano: In the piece, the loudspeakers become your partners in a game of proximity: you rearrange them within the space, searching for new meanings and compositions, striving to find the right assemblage. Cold sounds come out of them; sparse beats with militant hi-hats create a sort of emotionless chaos, echoing the raw energy of drum and bass. What is your relationship with this genre, and how do you engage with music, more broadly, in your practice?

Baptiste Cazaux: I love drum and bass, I play it a lot when DJing as well. Because of its disruptiveness through repetition, it makes me move in a certain way. It puts me into a dissociated state, which at the same time implies a full presence. It’s weird because it’s contradictory. I was interested in working with it for its symbolic aspects, and its links to rave culture. In addition, the aesthetic of jungle music encourages a post-apocalyptic, post-capitalist, post-industrial imagery.

I always begin with music, either as a topic, a support or as a way to create a mood, how it informs performative works on a conceptual or emotional level. In GIMME A BREAK!!! I have six loudspeakers on stage that I manipulate, plug, and unplug, to create a sonic environment. The disposition in regards to the audience is quite frontal, and thinking about the public’s perception helped me to relate to sound on a material level. I like the idea of labor linked to the weight of those speakers. There is a physical engagement, not only with them but with music as physical matter.

Chiara Pagano: At the very end of the piece, you’re sitting on one of them, with the shirt behind your neck. When the scene seems to be exhausted, another sound reaches the audience. It’s like birds chirping…

Baptiste Cazaux: This specific track is a MIDI track of birds doing beatbox. It adds humour and self-reflectivity to the work. The bird sound, to me, means finding peace, but for some, it evokes the end of the rave in the morning when birds start singing. When you create a work, it’s meant to be open to interpretation by others. I’m not keen on creating narratives, though I understand they can serve as a tool to find anchors in a work, and I appreciate that. For example, some people comment on the costume I wear while performing—a shirt, underwear, and sneakers—as if I’m going to attend a Zoom call during COVID. I never thought about that, I think it’s quite funny, though.

Federica Nicastro: The references to clubbing define analogies and shape a vocabulary that runs through your entire performance practice. It’s an important element which makes me curious about your parallel path as a DJ (under the pseudonym of Glaire Waldork). How did it start, and how does it relate to you, besides your performance practice?

Baptiste Cazaux: To me, there’s a connection that isn’t necessarily linear. I use DJing as a complementary practice that somehow influences my choreographic work. I don’t create music myself, so DJing for me is a way of combining different sounds, putting them on top of each other, and creating mashups and collages. It’s also about getting people to dance, which, in a way, comes from a place of generosity. I believe music is meant to be shared. I see my dance practice as a sound practice: to create listening environments for the audience, and sharing music and joy—which is also what I enjoy doing as a DJ.

My DJ name is Glaire Waldork. It’s actually a word play on a famous character of the Gossip Girl series, Blair Waldorf. ”Glaire” in French means “mucus”, which just sounds close to “Blair. While Waldork just sounds as dorky!

I started DJing during the first lockdown, it was March 2020, five years ago. I started developing a specific relationship to music, engaging with hardcore and superfast break beats. It was the kind of music that made me enter certain states through which I could release some inconvenient feelings like sadness and anger.

Federica Nicastro: You’re currently working on a new piece, titled That’s Twisted. This upcoming work seems to reflect more on a generalised and shared state of fear and paralysis, generated by multiple current or recent crises. What can you tell us about this upcoming work?

Baptiste Cazaux: That’s twisted is a piece that is going to be shown in 2026. I was doing some theoretical research in the studio when I came across an article by Dan DiPiero, called TiK ToK: Post-Crash Party Pop, Compulsory Presentism and the 2008 Financial Collapse. It debates on how pop music after 2008 reflected the mindset of young people at the time, who felt deprived of a potential future. Songs such as “Tik Tok” by Ke$ha, or “Party Rock Anthem” by LMFO, were part of that musical strand related to YOLO culture, and the idea of dancing until the end of the world.

I was very inspired by this article: how pop music could be a way to find catharsis in these moments, and how it influenced some states of mind linked to nihilism. The music coming out lately is inspired by a kind of aesthetic typical of the time of the financial collapse, when people wanted to channel their energy by partying until the world ends. A lot of references to French touch music, a lot of references to Crystal Castle, or indie rock music for example. Over the past few years, we’ve witnessed several musical revivals: a few years ago it was the ‘90s revivals. Now it’s the late 2000 revival. We always go back to the past in order to not think about the future. We always go back to the energies that were there to channel some kind of pleasure. Those were survival strategies at that time, and still are today. In order to embody these ideas, I want to create choreographic material inspired by party dances such as gabber, shuffle, or twists, to converge them into a sort of Frankenstein assemblage.

Because of all the crises that have been happening in these last years—the pandemic, the far right coming to power, the genocides, etc.—it’s complicated for me to imagine a bright future for humanity and for myself. Going into this nostalgia state is a way of making peace with the idea that a future might not exist. It’s completely irrational and personal.